The 1986 Paris-Dakar rally (2021)

Posted by admin on

[ comments ]

The 2021 Dakar Rally wrapped up on January 15, after 14 days and 7646 kilometers (4751 miles) traversing the unforgiving desert terrain of Saudi Arabia. Fifty-five-year-old Frenchman Stephane Peterhansel, the most successful competitor in Dakar’s history, won his eighth title in the car class (he also won the bike class six times in the 1990s), and Argentinian Kevin Benavides became the first South American rider to win the two-wheeled category. Russian Dmitry Sotnikov won the truck class. French rider Pierre Cherpin died from injuries sustained on the event’s 7th stage.

This was only the Dakar’s second running on the Arabian peninsula, but it was the 43rd iteration of the world-famous rally. The raid has gone through three continents over the decades, but its reputation for toughness and danger has never wavered. This year also marks 35 years since the 1986 running of the event, a year which gave rise to some of the greatest triumphs (and certainly some of the greatest tragedies) in the history of the Dakar Rally.

By 1986, the Paris-Dakar (as it was known then) was in its eighth year, and the competition’s amateur spirit was very much intact. But if an event as dangerous as Paris-Dakar ever had any wide-eyed naiveté, ’86 was the year reality set in.

Massive, professional factory teams had arrived in full force in all three classes (motorcycles, cars, and trucks), including three experimental supercars from Porsche. Sports car fans mainly remember the 1986 Paris-Dakar for those Porsches and their sparkling performance in the desert that year, but the event was also marred by rough weather and an especially treacherous route, which contributed to 1986 being one of the deadliest years in the event’s history. Six people lost their lives, including two participants, a famous singer, and the event’s founder and figurehead. Let’s take a look back at what the official Dakar website calls “The Black Year.”

Paris-Dakar’s origins

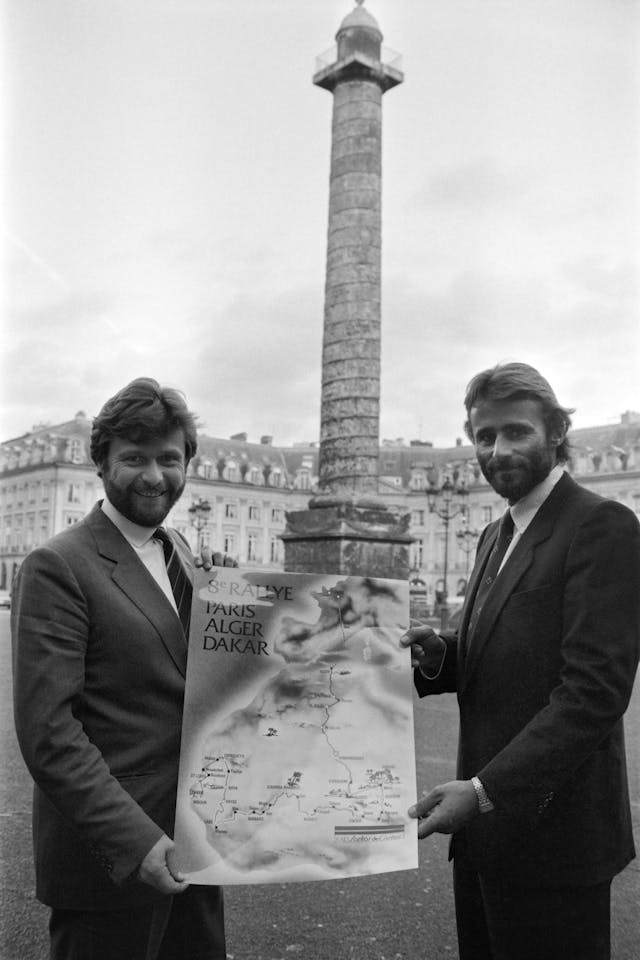

Back in 1977, while riding a Yamaha XT 500 in the Abidjan-Nice Rally, a wealthy French motorcycle racer named Thierry Sabine got lost in the Libyan desert. Forced to wait for rescue, he was captivated by the landscape and became inspired to organize a rally raid (essentially a long-distance, multi-day endurance rally) through the terrain. He wanted “to go beyond my limits and to take other people beyond theirs,” and in turn introduce the world at large to the natural beauty of the Sahara.

Sabine made it happen the very next year, and the first Paris-Dakar began the day after Christmas in 1978. The official start was at the Esplanade of the Trocadero, near the Eiffel Tower, and the race finished in the Senegalese capital of Dakar. The thousands of miles of punishing rocks, boulders, dunes, rivers, and other dangers in between took several weeks to conquer.

Of the 182 participants who set out from Paris, 108 failed to finish, and the event’s first fatality took place in Niger. The big winner was 21-year-old Cyril Neveu, of France, who won the event riding a Yamaha bike, while a Range Rover took fourth overall and first in the car class. A few dozen more adventurers found themselves tempted by the second running in 1980, and Paris-Dakar’s official motto became “A challenge for those who go. A dream for those who stay behind.” It quickly gained a reputation as one of the most grueling, most controversial, and most violent events of its kind anywhere in the world.

For the first few years, however, the Paris-Dakar entry lists were mostly full of French amateurs in lightly modified road vehicles. Many were in it just as much for the adventure as they were for the competition. One group tried to tackle the first rally in a 1920s Renault KZ, and a quartet of riders gave the 1980 event a go on their Vespas.

It wasn’t until 1982 that Paris-Dakar achieved mainstream international buzz, but hardly for rosy reasons. During the rally, in the desert near the Algeria-Mali border, Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher’s son Mark went missing. Serving as navigator in a rally-prepped Peugeot 504 that he called “the very worst car to do the trip in,” he made it most of the way through Algeria before the rear axle broke and stranded him, the driver, and the on-board mechanic. The organizers went looking for them—albeit in the wrong place—and newspapers ran headlines like “Maggie’s Son Lost in Sahara” and “Fears Grow For Lost Mark” as the trio waited six days, drinking water from the Peugeot’s radiator to keep from dehydrating, until their rescue.

From there, Paris-Dakar got a little more serious, attracting more determined competition beyond just amateur thrill seekers and eccentrics. The notoriety of the rally attracted more money, more corporate sponsorship, and OEM involvement. Big-budget factory teams were keen to score unforgettable PR value, and engineers wanted to put new technology to the toughest of real-world tests. Even stars of Formula 1 and sports car racing wanted a crack at the rally’s rigorous challenges.

All the while, danger persisted. The 1983 rally entered the Ténéré section of the south central Sahara for the first time, and 40 competitors (still navigating by compass and paper maps) got separated and became lost during a massive sandstorm. Jacky Ickx won the event in a heavily modified, Texaco-sponsored Mercedes G-Wagen.

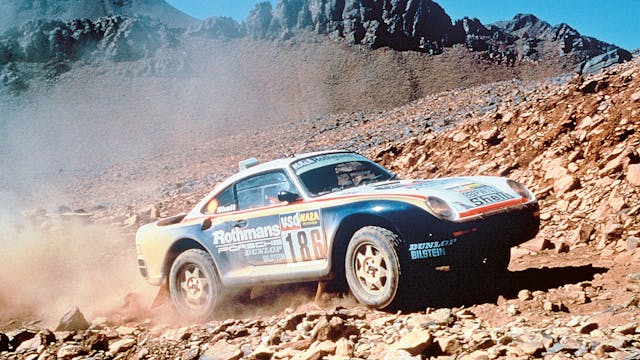

Porsche arrived as one of the first factory teams in 1984, enlisting Ickx to lead the effort sponsored by Rothmans tobacco. Despite garnering considerable skepticism for fielding a small sports car to an infamous vehicle-breaking trial like the Dakar, Porsche’s 953 (essentially a 911 with upgraded suspension and manually-controlled four-wheel drive system) silenced the naysayers by finishing first, sixth, and 26th. The influence of these rally Porsches can still be felt today.

The stage for ’86

A longer, more difficult route set the stage for the 1986 Paris-Dakar rally. Having worked long hours through the holidays prepping, checking, and figuring out logistics (international travel and shipping were a lot more complicated in those pre-E.U.days), the competitors officially set off on New Year’s Day from the Place d’Armes in Versailles.

Ahead of them were 15,000 km (over 9300 miles), almost none of it on paved roads and over half of it on special stages winding through seven countries and along several war-torn borders. In the Sahara, competitors could expect temperatures of up to 120 degrees F in the daytime, but below freezing at night. Traveling with them and accessible at night was a mobile base camp, or bivouac, offering food, few hours of rest, and time for vehicle repair and maintenance. Each day would start with a briefing with up-to-date information on the route for that day, but both the briefing and the road book provided were exclusively in French. The organizers planned for the whole thing to take about three weeks, with competitors divided up into three classes: bikes, cars, and large purpose-built trucks. (The parts-laden support trucks for the bigger-budget teams could technically compete in the truck class, too.)

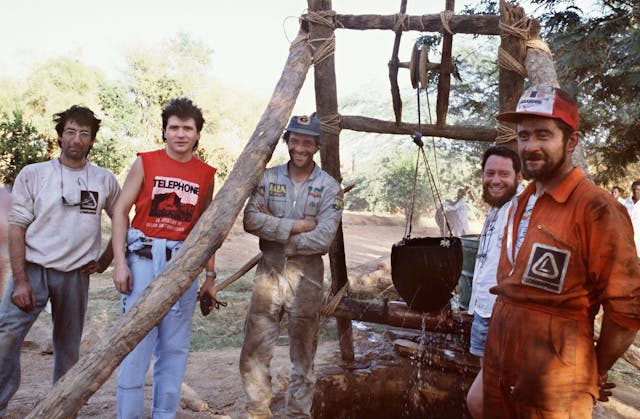

For 1986, the rally also announced it would donate water pumps to some of the villages along the route. Was this purely an act of goodwill? Maybe, but it was more likely a calculated hedge against bad publicity; the year before, the rally-goers bought up all the fuel in Timbuktu, and one charity reported a three-week shortage after it left.

According to the official tally, 486 competitors lined up at the start in Versailles, divided between 131 bikes, 282 cars, and 73 trucks. Star of the bike class and going for his third consecutive Dakar win was Belgian rider Gaston Rahier on a Marlboro-liveried BMW motorcycle, who said his “first opposition is the desert.” Rahier had plenty of other opposition as well. Honda developed a new NXR750 for the 1986 Dakar with a new 779-cc, 70-hp overhead cam V-twin, and the favorite on the Rothmans-sponsored Honda was 1979, ’80, and ’82 race winner Cyril Neveu. Hubert Auriol, the 1981 and 1983 winner, was also a favorite, riding for Cagiva.

The bike class was the most affordable to enter and thus hosted many amateurs paying their own way and performing their own repairs. For them, just finishing the rally would be victory enough. The car class, meanwhile, demonstrated how the desert can truly level the playing field. Nowhere else would you find Toyota Land Cruisers and Porsche supercars all vying for the same prize. Among the entrants was a group of German Opel Kadett 4x4s, Russian Ladas, and British Range Rovers. Mitsubishi, winners in 1985, arrived with even faster versions of its proven Pajero SUV. Among the privateers, and also running a Pajero, was Prince Albert of Monaco, having his second go at the event after failing to finish the year before. (A few days later, he would lose some of his royal luggage after the door of his Mitsubishi flew open mid-race.)

Porsche, winners of the 1984 event, were back with a vengeance after bad luck and a few tactical errors took all three of its cars out of the 1985 rally. The weapon of choice for ’86 was the 959, the full-fledged concept of a four-wheel drive competition supercar that had been carefully developed over the previous two years. With water-cooled heads and two turbochargers, it developed nearly twice the power of the winning 1984 car but was barely any heavier. Suspension included double wishbones and twin dampers up front, with double wishbones in the rear as well. There were more advanced touches, such as knobs on the dash to control ignition timing (the fuel in Africa could be as low as 75 octane), but also simple solutions: pieces of wood on which to set the jacks prevented the car from sinking into the Sahara sand.

The Rothmans Porsche team, fresh from a win in the 1985 Pharaoh’s Rally, fielded three 959s and brought over 20 people, two large MAN support trucks, a DC-3 chase plane, and a “fast service vehicle” in the form of a Mercedes G-Wagen packed with a Porsche 928S 4.7-liter V-8. Porsche even consulted a doctor to concoct special drinks with vitamins and electrolytes to keep the drivers, co-drivers, and mechanics in peak condition.

Piloting 959 #186 was 1984 winner René Metge, a desert specialist known for chain smoking Gauloises cigarettes, along with his co-driver Dominique Lemoyne. Jacky Ickx and Claude Brasseur were in another, while Porsche engineer Roland Kussmaul and co-driver Wolf-Hendrik Unger were in the other.

In the truck class were several purpose-built rigs, as well as the support trucks for the larger car and bike teams. But even some of the race trucks had their own support trucks, another sign of how this whole crazy enterprise had scaled up in the eight years since it began. Among the main competitors were some Spanish Pegasos and Czech Tatras, while the Minardi team—fresh from a disastrous debut season in Formula 1—made things harder for itself by braving Dakar in a CVS (Costruzione Veicoli Speciali) truck. Dutchman Jan De Rooy’s purpose-built DAF was the favorite; with two twin-turbo engines making 500 hp each, it boasted a 200-kmh (124-mph) top speed and promised to be as fast as the cars on some of the open stages.

Merciless fury

On January 1, the “Prologue” started from Versailles. This first stage through the relatively tame terrain of Europe determined the starting order when the rally reached the rough-and-tumble in Africa. As the competitors made their way from Versailles to the French port city of Sète, some 300,000 spectators turned out to watch the parade of loud bikes, cars, and trucks making their way across the country. The prologue was supposed to be the easy part, but things got off to a rough start. Weather conspired against the nearly 500 vehicles, and a snowstorm blasting through France made things particularly hard on the bikes, causing several wipeouts. Then, in a road accident in between stages, the 1986 Paris-Dakar Rally saw the first of several fatalities when Japanese rider Yasuo Keneko got hit by an automobile. Some reports cited a drunk driver as the cause of the incident.

With the starting order set following the completion of the Prologue, the rally departed on Algerian ferries across the Mediterranean with the vehicles, participants, organizers, fuel, and supplies. The next five stages through Algeria greeted competitors with rocks and boulders known for breaking axles and bursting tires. The retirements began to mount, as four-time Le Mans winner Henri Pescarolo’s Range Rover caught fire just 15 km into one of the first Algerian stages and burned to the ground.

The Rothmans Porsche team’s all-out assault wasn’t off to an ideal start, either. Having suffered problems in these stages the year prior, Porsche was purposely taking things easy, waiting for the more open desert in the southern Sahara to press their speed advantage. Even so, the team lost both the 928-powered G-Wagen support vehicle and one of the large MAN support trucks, so Roland Kussmaul’s 959 was loaded up with spares and relegated to the role of backup car. A spare intercooler and some radiators were strapped to the spoiler of his 959.

Algeria was hard on everybody, and the danger wasn’t just limited to the competitors. During the sixth stage, a loop through the Hoggar mountains that started and ended in the town of Tamanrassett, a helicopter filming the rally crashed right next to the route. One of its rotors had to be moved to allow the competitors to pass. Aside from that obstacle, the trucks in particular struggled to maneuver through the tall, steep mountain passes. Several tipped over while rounding tight bends.

For the seventh stage, the route went 828 km (514 miles) south from Tamanrassett in Algeria to Agadez in Niger. There were still rocks to hit, but the landscape mercifully opened up a bit. In the car class, which had the only night stage of the rally along this part of the route, the Porsches of Metge and Ickx were able to open up a convincing lead over the Mitsubishis that had been the early leaders. In the bike class, Gaston Rahier suffered a crash, cracking six ribs and breaking his collarbone, but he kept riding in hopes of a third win. He relied on acupuncture treatments at the end of each day’s ride.

Once the rally entered the Ténéré, the landscape opened up to wide open sand, deep dunes, the horizon, and little else. The only real points of reference were a metal tree sculpture and a downed aircraft—a press plane that happened to crash during the 1985 Paris-Dakar Rally while going in for a close-up. It was both a landmark and a warning.

Porsche driver Roland Kussmaul compared the varying terrain to surfing, because the Ténéré has “small up and downs, and with the car you go up and fly down, up and fly down. And it was easy, it was soft, it was not harsh … So you sit in the car and you are smiling. But then, when you hit a step in the sand, it steps down and the smiling is gone.”

The stages winding to Dirkou and Zinder (both in Niger) saw steeper, more dangerous grades. There may not have been boulders, tree stumps, or livestock to hit, but the combination of deep sand and steep dunes with rapidly moving vehicles proved even more dangerous than the rocky and mountainous parts of the desert. Flying through the sand on his Cagiva, Hubert Auriol launched into the air on his bike over one dune and wiped out. While uninjured, he lost precious time restarting his motorcycle. After nosediving over a ridge, both codrivers in one of the Czech Liaz trucks suffered internal injuries, while a Range-Rover Proto flipped over a dune and crushed the roof. Jan De Rooy’s DAF became so bogged down in the sand that it had to be dug out with shovels. The Minardi team’s CVS truck, meanwhile, experienced an electrical fire and completely torched itself. The truck had been in second place.

Then came the sandstorms. The air fleet that normally follows the rally was grounded. With mounting injuries among the competitors, the organizers commandeered a Hercules aircraft to use as a mobile hospital. Veronique Anquetil, a 26-year-old Yamaha rider, was one of several to crash in the dunes before being carried unconscious to the bivouac at the end of the stage. Jean Michel Baron, one of the top-running Rothmans Honda riders, was even worse off, sustaining serious head injuries in the dunes. Doctors operated in a makeshift hospital area at the edge of an airstrip, but both Baron and Anquetil were ultimately airlifted to hospital in Paris. Baron fell into a coma, from which he never awoke. He passed in 2010.

After 14 days, the rally reached the two-thirds mark. Fewer than one-third of those who set off were still in the running. Just 99 cars, 44 bikes, and 37 trucks reached the Niger River. On the 12th stage of the rally, from Niger’s capital of Niamey to Gourma, 1985 winner Patrick Zaniroli, in a Mitsubishi, got lost and received a 10-hour penalty for not finishing the allotted distance in time. Meanwhile, on the evening of January 14, amid worsening sandstorms and as the rest of the aircraft associated with the rally remained grounded, event organizer and figurehead Thierry Sabine took off in his white helicopter, nicknamed Sierra, on another mercy mission looking for lost competitors. Sabine was frequently dressed in a white jumpsuit and he wore his blonde hair long. He also kept a beard, and all this naturally that led to the nickname “Jesus” as lost Dakar competitors could frequently count on Sabine coming to their rescue.

After January 14, 1986, they couldn’t count on him anymore. Near Gourma-Rharous in Mali, Sabine’s helicopter crashed in the midst of the sandstorms, killing everyone on board. Sabine, 36 years old and engaged, was on board with famous French singer Daniel Balavoine, 25-year-old reporter Nathalie Odent, journalist Jean-Paul Le Fur, and pilot Francois-Xavier Bagnoud—a cousin of Monaco’s Prince Albert. Some wondered if the rally would be stopped then and there, but the organizers decided to continue on, noting that it was what Sabine would have wanted. They did, however, cancel the January 15 stages. The competitors who were left made a silent convoy to Bamako in Mali. Sabine’s deputy, Patrick Verdoy, took the reins for the remaining stages.

Upon arriving to Labe in Guinea, the organizers announced an extra rest day (usually there is only one rest day for the entire event). Several members of the Rothmans Porsche team had their passports stolen before leaving Labe, but the 959s had a comfortable lead in the car class and filled the top three places. But as the landscape changed to trees, rocks, streams, and villages, their outright speed and power advantage diminished. Jan de Rooy’s twin-engine DAF truck, which had been seriously fast so far, broke its front axle and retired as the rally moved to Mauritania. Meanwhile, Gaston Rahier on the Marlboro BMW suffered more bad luck, with two flat tires and a gearbox problem delaying him enough to earn a 10-hour penalty and dash his hopes for a win. With nothing left to lose, he threw caution to the wind and pushed hard on the last three stages, finishing first in all three just to prove a point.

As at the dunes of the Ténéré, the crossing at the Senegal River proved to be a major impediment that would unexpectedly shuffle the standings. An abnormal amount of rain for that time of year brought lots of mud, too much for the top three contenders in the truck class to manage. Suddenly, the Mercedes Unimog support truck for the Honda of Italy motorcycle team found itself in the lead.

Meanwhile, in the car class, the Porsche team was witnessing an emerging threat to its once-comfortable lead. Both Metge and Ickx’s 959s got stuck in the mud. Roland Kussmaul, in the third 959, then watched carefully how one of the motorcycles crossed the river, and he successfully followed the same path before turning around to help the other two Porsches. Using some spare cable, he was able to pull both other cars to safety; in the process, however, his own car sunk down to the hubs in thick, gloppy earth. Metge and Ickx wanted to stick around to help, but Kussmaul honorably sent them on their way to take the class win. After digging himself out and making his way to the bivouac, he was too exhausted to speak and had to see a doctor. Had he gone on ahead instead of helping his teammates, he might have won the entire 1986 Paris-Dakar Rally.

Reaching Dakar

Exactly three weeks after departing Versailles, just 100 competitors (fewer than 21 percent) reached Dakar. There were just 29 bikes and a handful of trucks at the finish along the beaches of Lac Rose, a salt lake known for its pinkish water.

The last stage was a short 60-km dash down the beaches. After three weeks’ worth of racing, the finishing order was typically set by this point, and the final side-by-side sprint on the sand was more a procession for the finishers than a serious competition stage. Yet even here danger lurked, as both water and wet sand posed tangible threats. Cagiva rider Giampaolo Marinoni crashed and died just 40 km from the finish.

Understandably, celebrations were subdued out of respect for the fallen, but the finishers had all accomplished something remarkable. Cyril Neveu on the Rothmans Honda took his fourth bike win (he won again in 1987). The Rothmans Porsche team took first and second, while Roland Kussmaul came home sixth despite his sacrifice (which included carrying piles of parts for the other two cars). The 959 had proved its worth, and a production version followed that would be the fastest and most technologically advanced road car at introduction. In the truck class, the surprise winners were Giacomo Vismara and Giulio Minelli in the Mercedes support truck for the Honda of Italy bike team.

Endurance rally

After Sabine’s death in the 1986 event, many wondered if the rally could or would continue on at all, but it persisted. Porsche, having achieved its goal, didn’t come back for 1987 but another big factory team arrived to take its place. Peugeot, stuck with obsolete 205 rally cars after the FIA banned Group B rallying in Europe the year before, brought them to Africa and won the car class with 1981 WRC Champion Ari Vatanen at the wheel. Cyril Neveu won yet again in ’87, after Hubert Auriol broke both his ankles in a fall. Jan de Rooy came back to win the truck class.

Criticism of the event was gathering steam. A 1988 New York Times article quoted one French group campaigning to end the Paris-Dakar, criticizing it for using “Africa’s poorest corner as a playground for the rich.” A company called ASO bought the rally in the early 1990s, but despite more corporatization and sponsorships its fearsome reputation carried on. A journalist once quipped that Paris-Dakar was “like war without the bullets,” but sometimes there were actual bullets. In 1991 a support truck driver for the Citroën team was shot dead, and the Malian army escorted the rally through the rest of the country. In 1996 another support truck driver ranover an old Moroccan army land mine and died. But the final nail in the rally’s coffin, at least in its original form, came years later. When terrorist groups in Mauritania threatened the 2008 rally directly after the slaying of four French tourists there on Christmas Eve 2007, the event was shuttered and moved to South America for 2009 with the “Dakar Rally” name intact. It’s unclear if the Dakar Rally will ever go back to Africa, but the event appears to have found a successful home in Saudi Arabia after the last two years in that country.

There are endless stories that come out of the Dakar Rally in any given year, but 1986 was the most eventful iteration of an already notoriously crazy event. No doubt the competition will continue to be a source of adventure for as long as it endures.

[ comments ]