My Grandfather Participated in One of America’s Deadliest Racial Conflicts

Posted by admin on

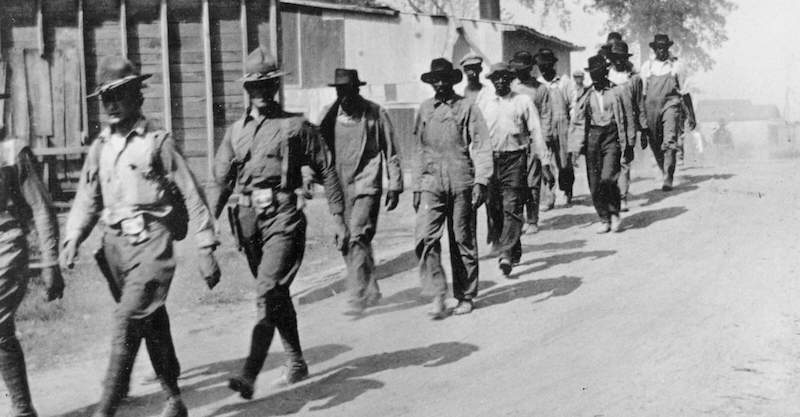

Across the sweeping canvas of American history, two markers, inherited and ineluctable, from the Elaine Race Massacre of 1919 in Phillips County, Arkansas, invite a degree of attention yet to be fully received from the country’s public consciousness. First, the sheer number of persons who died in the Massacre—more particularly, the countless African-Americans who perished—would certainly cause this massacre to be judged one of the deadliest racial conflicts, perhaps the deadliest racial conflagration, in the history of the nation.

Second, the American Civil Rights Movement during the 1950s and 1960s drew constantly from the wellspring of the 1923 U.S. Supreme Court’s decision in Moore v. Dempsey that emerged out of the legal proceedings in Phillips County against African-American defendants, charged with the murders of whites allegedly committed during the Massacre. The ruling in Moore v. Dempsey broke a long chain of Supreme Court decisions brutally adverse to the safety and rights of African-Americans.

Two heroes whose individual backgrounds could not have been more dissimilar share in this saga of a changing of America. Most apparent, Scipio Africanus Jones, African-American lawyer, who began work in Arkansas’ fields to become a 20th-century Moses, climbed, through brilliance and tenacity, to forensic heights to free the black sharecroppers, unjustly found guilty of crimes in the aftermath of the Massacre. At the same time, he developed the legal strategy that ultimately, through the intervention of the U.S. Supreme Court, gave life to the Fourteenth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution to guard the individual rights of and due process for American citizens.

The other hero, Oliver Wendell Holmes, Boston patrician and distinguished jurist, who wrote the majority opinion for Moore v. Dempsey, not only opened the door to freedom for wrongfully convicted Arkansas sharecroppers, but also articulated a new judicial precedent and principle under which the federal government would more forcefully thereafter engage in the constitutional protection of all its citizens.

Notwithstanding the historical and legal significance of the Elaine Race Massacre, outside a handful of advocates and a somewhat wider audience that those advocates engendered, the Massacre and its aftermath have been largely ignored. Whether this inattention can be explained by the Massacre’s remote location, by the desire of many blacks and whites in Phillips County and throughout Arkansas to keep quiet about the conflagration, or by the rush of other affairs affecting the state and the nation, we just don’t know.

It is certainly time for more airing of those days at the end of September and early October, 1919, and subsequent, associated, and gravid moments, if, for no other reason, than to debunk the erstwhile success of silence and avoidance.

Whenever she mentioned the race riot, Mother frequently referred to my grandfather Lonnie, in a matter-of-fact tone, as a member of the Ku Klux Klan.By the time of my birth in 1944, my maternal grandparents, Alonzo Birch, known as “Lonnie,” and Hattie, had moved to Little Rock from McGehee when he was transferred by the Missouri Pacific Railroad (MoPac) from the company’s southeastern Arkansas hub to its larger transportation center. Lonnie was thin, not tall, not short, white, and a native of the Arkansas Delta. Bespectacled with large pale frames, he had thick, often unmanageable gray hair. An inveterate smoker and a proud agnostic, Lonnie bore a tranquil demeanor, and for me, remained always available. At the time Lonnie became my principal caretaker, he was retired from MoPac, which had an indelible and indisputable part in the Elaine Race Massacre.

For several years following my father’s death in 1946, before I had reached the age of two, I lived with Lonnie and Hattie until my mother brought my older brother and me together under one roof in Monticello, one of the many small towns in southeast Arkansas. Upon our father’s death, my brother spent much more of his time with the paternal side of the family. Soon after I left Lonnie for Monticello, he died of a cerebral hemorrhage, but even today, I reminisce over the love and sensibility we shared with each other.

I can recall times I sat in his lap on the front porch of my grandparents’ home in Little Rock, when Lonnie and I watched cars and people go by, and I played with a porch chair that could be overturned and magically—soon after the end of World War II—become a fighter pilot’s cockpit. Lonnie and I celebrated birthdays and other holidays together. When I fell down, he picked me up and gently assuaged my scrapes and bruises.

Out of the blue—I must have been in junior high school—without provocation or for any apparent reason, except that the integration of Little Rock Central High School had just begun, Mother casually mentioned that before she became a teenager, Lonnie participated in a “well-known” race riot while in the employ of MoPac. Later on, she editorialized about it now and then: how he traveled on a MoPac train from McGehee to the battle between the races, how the place of bloody engagement with the blacks had been close to the railroad tracks and among cotton rows.

Looking back at the time that followed the end of World War I, when the Elaine Race Massacre occurred, what other race massacre or so-called race riot had there been near McGehee, except for Elaine? There wasn’t one. History did disclose lynchings or the burning alive of African-Americans around that time in Star City, Monticello, McGehee, and Lake Village within southeast Arkansas, but no massacre or riot, except for Elaine. Whenever she mentioned the race riot, Mother frequently referred to Lonnie, in a matter-of-fact tone, as a member of the Ku Klux Klan.

At the time of the Elaine Race Massacre in 1919, Lonnie worked as a railroad engineer for MoPac. The Birch family, pioneer residents of Desha County, immediately south of Phillips County, consisted of planters, but, unlike other male family members who chose to farm, Lonnie instead took a job with MoPac in McGehee, only a few miles from the Birch farms. Home for Hattie, Lonnie, and their several children and a relatively short train ride to and from Elaine, McGehee had become MoPac’s regional center for southeast Arkansas.

My grandfather was who he was, and now that he is dead, I can only ponder the questions with the answers secluded and forever distant.If anyone in that part of the country found it necessary to get to Phillips County by railroad, the easiest mode of non-local land travel in the early part of the 20th century, the path generally led through McGehee. Arkansas Governor Charles Hillman Brough brought federal troops from Little Rock to Elaine via McGehee to “restore” order, and except for those coming through Memphis, outside contributors or witnesses to the Elaine Race Massacre, if they came by rail, were likely to pass through Lonnie’s hometown.

Much later, I made the simple connection that the race riot to which Mother alluded and the Elaine Race Massacre were one and the same. It was not very difficult to conflate the related factors leading to Lonnie’s participation in the Massacre: his employment with MoPac; the routine, quasi-police role MoPac undertook during that time in that region of the state; Lonnie’s chthonic views about race, evidenced by his membership in the Ku Klux Klan; and the history, conveyed by Mother’s verbal remembrances.

I had learned that Lonnie, though employed by MoPac, kept in contact, for kinship and financial reasons, with his brothers who farmed the family lands, and would have therefore undoubtedly known of the rumored threats of unionization by African-American sharecroppers in the Arkansas Delta to negotiate for higher cotton prices with the white planters. After all, Robert Hill, the black organizer of black sharecroppers, and his Progressive Farmers and Household Union, both being indivisibly bound to the Massacre in Phillips County, resided in Winchester, a small hamlet only a handful of miles north of the family farm.

I can indeed link the convincing pieces that led to the conclusion Lonnie took part in the Elaine Race Massacre, but I cannot reconcile my love for Lonnie and his apparent views about and contributions to racism, as practiced in the Arkansas Delta by whites during the first part of the 20th century. In my readings that dealt with the period, I recollect references to the Arkansas Delta as the heart of darkness for African-Americans, and it may have been—with my own grandfather’s propensity adding, in goodly supply, no doubt, to the pool of darkness that spread murderously and perniciously over the land.

Yet, he was always kind to me, much kinder than virtually anyone else. So, I will not try to reconcile the two—it would be false, serpentine, and artificial. But maybe he couldn’t reconcile the two either. He was who he was, and now that he is dead, I can only ponder the questions with the answers secluded and forever distant. Still, I know unreservedly my own path to Elaine was, in part, to uncover a slice of him that eludes my memory and baffles my personal conscience.

__________________________________

Excerpted from Damaged Heritage: The Elaine Race Massacre and a Story of Reconciliation by J. Chester Johnson. Copyright ©2020. Available from Pegasus Books.