Sometimes Taking Things Out Counts as Writing: an Interview with Celeste Ng

Posted by admin on

Editor’s Note: For the first several months of 2022, we’ll be celebrating some of our favorite work from the last fourteen years in a series of “From the Archives” posts.

Our first feature is a conversation between founding editor Anne Stameshkin and Celeste Ng, who was one of FWR’s original contributors, as well as the former editor of our blog. The two discuss Ng’s debut novel, Everything I Never Told You. This conversation originally appeared on June 30, 2014.

Celeste Ng and I met almost exactly a decade ago in the University of Michigan’s Creative Writing MFA program (now the Helen Zell Writers’ Program). We were in the same fiction workshop every semester, and I remember devouring her stories with a hunger that felt both familiar and new. Her prose was delicious; her stories, dark and moving. I would read anything this person writes, I thought, and told her as much.

Over the years, our friendship has deepened as we’ve read and edited each other’s work, and helped build Fiction Writers Review. I was lucky enough to read several drafts of her first novel, Everything I Never Told You (Penguin Press), and to see it evolve from an ambitious first draft to the gorgeous, brilliant book that just published with starred reviews from Publisher’s Weekly, Booklist, and Library Journal. Set in 1970s Ohio, Everything I Never Told You opens with the revelation that Lydia, the beloved middle child of a Chinese American family, is dead—but her family doesn’t know this yet. The search for the missing teenager and then the grief after her body is found in the lake threaten to drive her family apart just when they need each other the most. Moving artfully among characters’ perspectives, the novel shows how Lydia’s mother, Marilyn, her father, James, and her siblings, Nathan and Hannah, each seek to unravel the how and why of her death—and we also get time with Lydia herself in the days leading up to her disappearance.

Celeste Ng’s fiction and essays have appeared in One-Story, TriQuarterly, Bellevue Literary Review, the Kenyon Review Online, and elsewhere, and she is a recipient of the Pushcart Prize. She teaches fiction writing at Grub Street.

Interview:

Anne Stameshkin: Celeste, the writing in Everything I Never Told You is so beautiful line by line, something I’ve always admired in your short stories. How did you maintain such high-quality prose in a longer form?

Celeste Ng: Thank you! I write by ear, so the language is very important to me all throughout the process. It all has to sound right at every stage or I can’t move on. I’m always polishing as I go, which can make for very slow writing.

How much of the language comes as you initially draft, and how does it change as you revise?

My sister is an engineer, and one of the rules of engineering is that first you make it work, then you make it elegant: in other words, you don’t worry about complexity and aesthetics until you have a prototype that gets the basic job done. I envy those who can write that way: rough out a scene without worrying about the language, then go back and add detail when the basic story is in place. My process is more like painting every brick as I lay it, when maybe getting all the walls up first would be smarter. But that’s how I work.

How did you decide on the book’s structure, and why did it feel right for this particular novel?

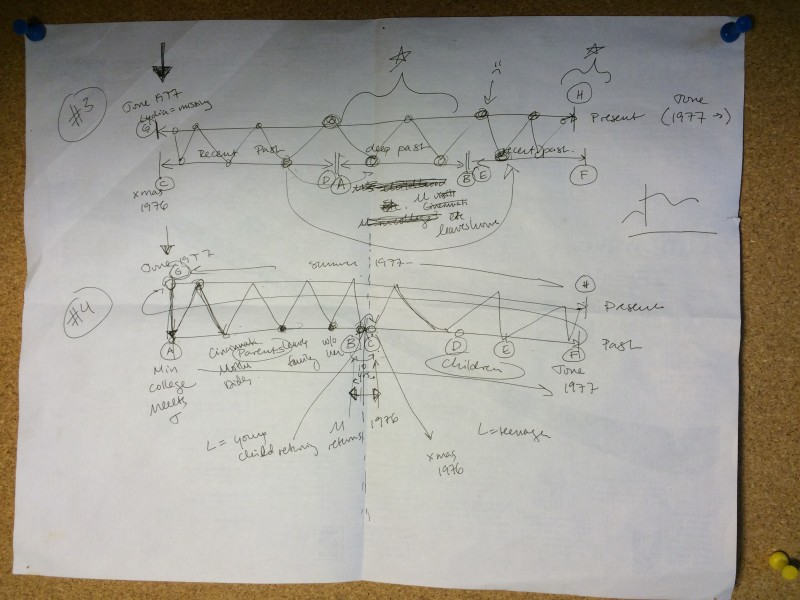

Oh, the structure. The structure. It changed dramatically in every draft. I knew past and present were equally important in the novel—it’s just as much about why Lydia’s death occurred as how her family reacts to it—but I struggled for a long time to figure out how to link them. There’s a long bulletin board in my office, and at one point the whole thing was covered in 3×5 cards, all color-coded and laced with string as I tried to work it out.

I started with a multi-part structure: two chapters in the present, then three chapters from Lydia’s childhood, and so on—but it killed the momentum. Then I tried three braided timelines—present, recent past, deep past—but the backstory overwhelmed the present story. Then I condensed those three timelines into two—that was your idea, actually, Anne! You read draft #2 and said, “I have no idea how to do this, but it would work better if you had only one past timeline.” I had no idea, either, but you were completely right, and somehow it got done. But then the novel jumped in time a lot; the reader got whiplash.

So in the fourth draft, I tried to straighten out the chronology. Just before that revision I went out to dinner with my husband, had a flash of insight, and ended up drawing this insane diagram on the back of my placemat.

I don’t think he totally understood, and I’m not sure I can even explain the diagram now, but it helped me get that last draft done.

Ng’s Novel Structure Diagram for Everything I Never Told You

That’s fascinating. I love peeking behind the curtain at other writers’ notes and processes. I think it helps anyone working on our own books to see how others keep their timelines and information straight. How did all this thinking about structure impact the final draft?

To my surprise, in the final version, the structure became quite orderly. There are two timelines, both moving forward: the present timeline starts with Lydia’s death and goes on to show its aftermath, while the past timeline starts when Lydia’s parents meet, then moves through her childhood and up to her death. There’s a clear pattern—present, past, present, past—and at each “handoff” there’s a reason for switching from past to present. For example, Chapter 3 ends with Marilyn searching Lydia’s diary for clues about her death, and Chapter 4 begins with five-year-old Lydia getting her first diary.

Hopefully, when you read the novel, you won’t notice all that unless you’re actually looking. When structure is done well, it should be like architecture: you sense the overall feel of the building—tall, or airy, or strong—but you’re not looking at the buttresses that hold it up or the seams where parts are fastened together.

Let’s talk about the beginning of the novel. In earlier drafts of the book, what happened to Lydia—was she alive or not—was a mystery for a good part of the novel. Why did you decide to tell readers “Lydia is dead” in the first sentence? How does shifting the mystery’s focus from what to how and why change the story?

That first sentence didn’t fall into place until the very last draft. Every other draft began, “At first they don’t know where Lydia has gone”: deliberately withholding information vs. laying the narrative cards on the table. The credit for that is a long talk I had over coffee with [University of Michigan alum and former classmate] Elizabeth Ames Staudt, who asked, “Is there a reason to withhold that Lydia is dead, other than to create suspense?” She advocated giving that information in the first chapter, to keep the focus on how this happened rather than on whether Lydia was dead or alive.

I thought this was brilliant advice and ended up putting it in the first sentence. The novel was going to have to be strong enough to keep a reader’s interest even after he or she learns Lydia is dead—so I might as well put it right up front! It’s really too big a thing to conceal. I never wanted to write a whodunit, and putting “what” out there right away signals readers to focus on the “why”—the family dynamics that lead to this tragedy—which is more interesting to me.

Point of view is something you and I have spent hours talking about, in workshops (particularly with Peter Ho Davies), over meals and manuscripts, and once even in a collaborative online discussion of How Fiction Works. How much did you think about who was telling your novel’s story and the relationship between your narrator and the characters? How did you find your narrator?

The narrator also came late to the party. Earlier drafts were in multiple close third-person POVs, but with five main characters, I was covering a lot of ground twice to show it from different perspectives, and it was hard to link past and present. I needed something to pull all the pieces together, and an omniscient POV seemed like the right way.

But I didn’t know how to write an omniscient POV, so I spent a lot of time looking at books that used one—The Known World, The God of Small Things, Amy and Isabelle, Bel Canto—to try and figure out how they’d done it. Omniscient POV is often called the “god” perspective, but I ended up with someone who’s more like a teacher: someone giving you context along the way to help you interpret what you’re seeing. I wrote about this for Glimmer Train, if anyone is curious to read more.

But I didn’t know how to write an omniscient POV, so I spent a lot of time looking at books that used one—The Known World, The God of Small Things, Amy and Isabelle, Bel Canto—to try and figure out how they’d done it. Omniscient POV is often called the “god” perspective, but I ended up with someone who’s more like a teacher: someone giving you context along the way to help you interpret what you’re seeing. I wrote about this for Glimmer Train, if anyone is curious to read more.

Actually, omniscient POV is used more often than we think it is and less often than it could be. In third-person, for instance, we often have to use juxtaposition to imply connections between events: these things are next to each other, so they must be related. That works to a certain extent, but it asks the reader to do all the assembly when it comes to making meaning. An omniscient narrator can help do some of that work for the reader.

When you started drafting this novel, you weren’t yet a mother; you revised it while raising a baby boy. How, if at all, did the experience of parenthood change your perceptions of your characters who were parents, too, and who lost a child?

Becoming a parent made me much more sympathetic to James’s and Marilyn’s points of view. Not to say that I agreed with all their decisions, of course—but I had a much clearer understanding of why they might make them. And it made revising the scenes where they grieve their daughter very painful to write, much more than I’d expected. I would sometimes write at night and then sneak into my son’s room to hug him and just watch him breathe for a while.

Who are two writers or what are two books that most spoke to you while working on this novel, and how/why?

Bel Canto, by Ann Patchett, woke me up to the idea of an omniscient narrator and was the first book I turned to for POV help. Elizabeth Strout’s debut novel, Amy and Isabelle, was also helpful for POV, and it’s also a story about secrets, and a mother-daughter relationship grown toxic and suffocating—all themes in my novel, too.

What are some books you’d recommend to fans of your novel?

Amy and Isabelle, by Elizabeth Strout, which I mentioned above. Evening Is the Whole Day, by our classmate Preeta Samarasan—another story of secrets corroding a family from within. You Are One of Them, by Elliott Holt—a novel with a narrator haunted by loss and grappling with how well (or whether) we can ever understand anyone.

What single piece of writerly advice (or essay/book about process) did you find most helpful as you were working?

While writing a novel, I think you naturally become omnivorous—at least, I did. You listen to anything and everything in case it helps. Taped above my desk are three quotes. From Preeta Samarasan: “It pretty much feels impossible until you’re done. It continues to feel impossible all the way through. I only began to acknowledge that it might be possible to finish when I was about 2 chapters from the end.” From Peter Ho Davies: “Progress and productivity are often a question of morale, not output.” And the classic from E.L. Doctorow: “Writing a novel is like driving a car at night: you can see only as far as your headlights, but you can make the whole trip that way.” They all boil down to the same thing: no one knows what they’re doing, so just keep going.

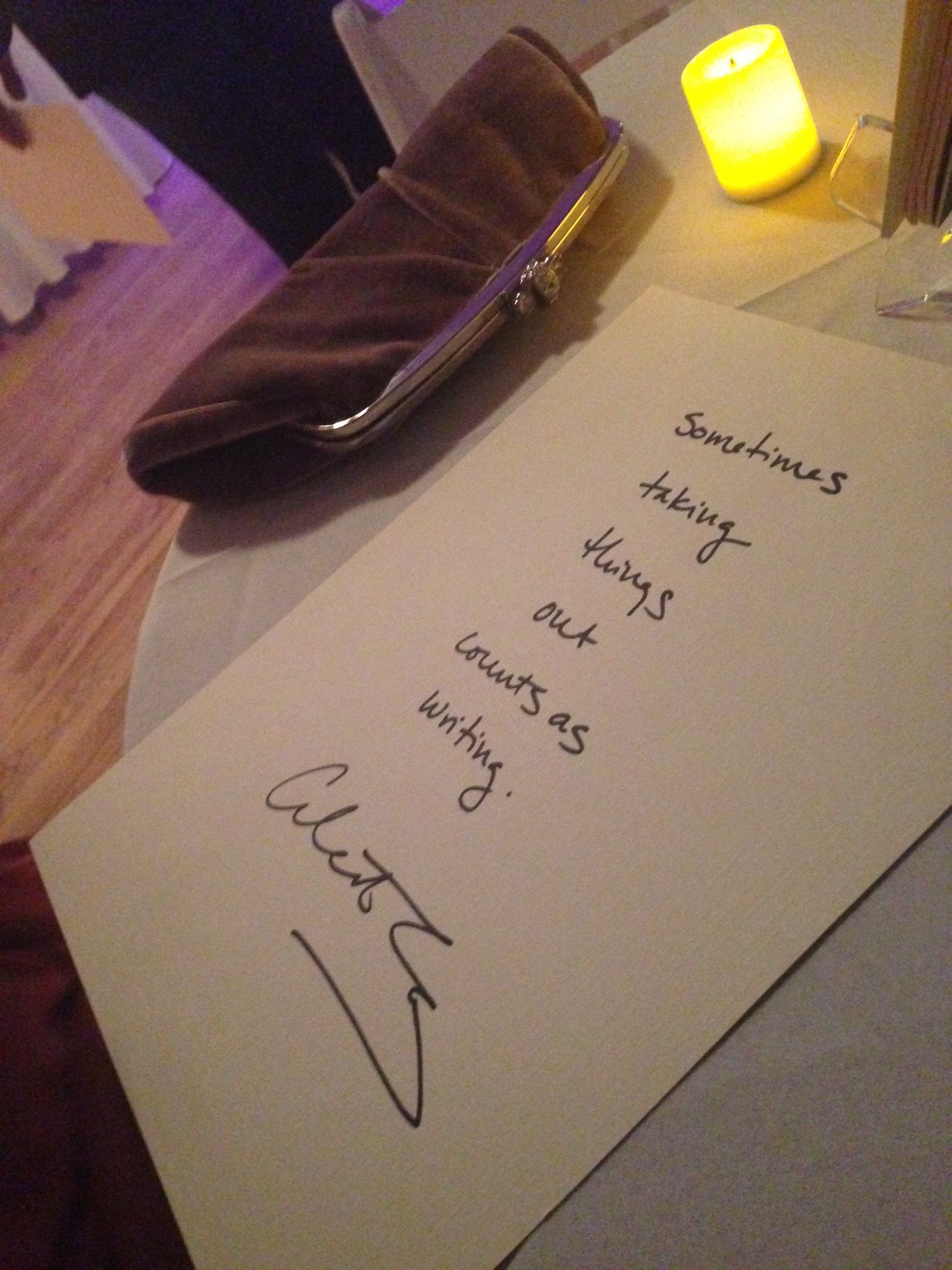

Advice—the writerly kind—was the theme of this year’s One-Story Debutante Ball, where you were honored as a 2014 debutante. Famous writers auctioned off handwritten words of wisdom, and as a debutante, you contributed your own: “Sometimes Taking Things Out Counts as Writing.” What did you most enjoy about the ball? And can you describe this exciting annual event to our readers?

Advice—the writerly kind—was the theme of this year’s One-Story Debutante Ball, where you were honored as a 2014 debutante. Famous writers auctioned off handwritten words of wisdom, and as a debutante, you contributed your own: “Sometimes Taking Things Out Counts as Writing.” What did you most enjoy about the ball? And can you describe this exciting annual event to our readers?

The One-Story Debutante Ball is One-Story magazine’s annual fundraiser: each year, they honor authors they’ve published who are now publishing their own debut books. It’s a spoof on the old-fashioned debutante balls, so everyone gets dressed up, and each “deb” is escorted down the aisle by a mentor, someone who’s been important to their writing and career. And I asked you to escort me, since you’ve not only been a dear friend, but you’ve also read my novel drafts, you helped me write my first reviews and essays and blog posts at FWR, and you’ve given me sage advice on all things writing for years.

The best things about the ball were—in no particular order—(1) getting dressed up, with head bling, and seeing all the other writers in their finest; (2) meeting and reading the next day with the other debutantes—I remembered most of their One Story stories and harbored literary crushes from afar; (3) seeing the first lines from all of our books set as streamers above the dance floor; and (4) partying with you and other NYC-based writer friends. Oh, and seeing all those writers dance!

Seeing writers dance is always fantastic, but these attendees really caught the fever.

Almost as fun as being a reader for this project over the last several years was helping you shop for your forthcoming book tour. While walking the dressing room runway at Macy’s, we talked (and joked) about an author persona–what it is, what yours might be, and the pressure in current publishing culture for authors–particularly women–to market themselves as well as their books. I imagine it’s both an exciting time and a fraught one, putting yourself out there. Can you characterize the persona that is “Celeste Ng, Author,” and describe how you answer to the pressures of publicizing the results of what was at first a fiercely private act of writing a novel?

Writing is so solitary, and so different from publishing and publicity. I’m incredibly lucky to have that opportunity, but I’m still trying to wrap my mind around the idea that this book is Out There. It’s a little like dancing around like a nut in your apartment and then realizing the curtains are open and people are watching: oh my god, people can see me! So I’m still working on the persona, but as much as possible, I’m trying to make it genuinely me, or at least the person I hope to actually be: informed but irreverent; thoughtful with a generous dash of whimsy; passionate, but not drinking anyone’s Kool-Aid. Okay: also a little more articulate, and much better dressed.

Anne Stameshkin and Celeste Ng at the One-Story Debutante Ball