Book Review 018 / Alice in Wonderland by Lewis Carroll / The never-ending adventures

Posted by admin on

Alice in Wonderland: the never-ending adventures

Since its publication 150 years ago, Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland has kept a powerful grip on the public imagination. Robert Douglas-Fairhurst explores the origins and afterlife of Lewis Carroll’s famous creation

Robert Douglas-Fairhurst

Friday 20 March 2015

One of the strangest creatures Alice meets in Wonderland is the Caterpillar, who languidly asks her “Who are you?” and receives the uncertain reply: “I – I hardly know, sir, at present – at least I know who I was when I got up this morning, but I think I must have been changed several times since then.” Alice’s confusion is understandable – over the course of her adventures she is variously mistaken for a housemaid, a serpent, a volcano, a flower and a monster. Today the Caterpillar’s question would be even harder to answer. Who is Alice?

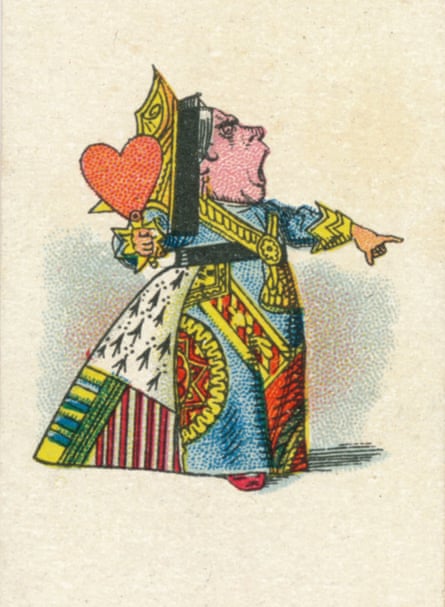

Since the first publication of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland 150 years ago, Lewis Carroll’s playful and puzzling work has spawned a whole industry, from films and theme park rides to products such as a “cute and sassy” Alice costume (“petticoat and stockings not included”). Whether she is being viewed as an icon of innocence or an opportunity to play out more disturbing fantasies, the blank-faced little girl made famous by John Tenniel’s original illustrations has become a cultural inkblot we can interpret in any way we like.

|

| Lewis Carroll |

In her anniversary year, theatrical highlights include a highly inventive production of Alice’s Adventures Underground, which opens next month in the Vaults deep underneath Waterloo Station, and in July the Manchester international festival premiere of Damon Albarn’s musical Wonder.land, directed by Rufus Norris. There will be exhibitions at the V&A Museum of Childhood and the British Library, a special set of stamps issued by the Royal Mail, and whole bookshelves of new publications. Once again, Alice will prove to be as hard to pin down as a thought bubble.

Usually she is simply taken for granted. Although we might enjoy her feats of literary escapology, repeatedly wriggling out of the covers of her original book, we rarely stop to think about why it is Alice, rather than other fictional characters such as Heidi or Dorothy, who has come to exert such a powerful grip on the public imagination.

My own memories of the Alice books go back much further than my earliest memory of reading. They were always there, full of quirky figures that helped to populate the busy borderland where real life shaded into the world of stories, and that is where they remained for the next 40-odd years. I visited Wonderland as a reader from time to time, but for the most part Carroll’s story remained quietly in the background. Only when I started to investigate Alice’s literary birth and afterlife did I discover that I knew far less about her than I had assumed.

When Henry James described the creative process that lay behind his novel The Ambassadors, he pointed out that “There is the story of one’s hero”, but also “the story of one’s story” – a hidden timeline that involves much staring into space and cursing the empty page, punctuated by those rare moments when words can be shuffled into a sequence that will make them sing. However, if an unfinished piece of writing is a work in progress, the same is true of a book that continues to morph into new shapes after publication. And from the “golden afternoon” on 4 July, 1862 when Carroll first dreamed up his story, to the global popularity it enjoys today, Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland has never stopped being a work in progress.

The afternoon on which Carroll tried to entertain the three young daughters of his Christ Church, Oxford, colleague Dean Liddell has since become almost as famous as the story itself. Many years later, Carroll and his unwitting muse, the 10-year-old Alice, separately recorded their memories, and although they differed in some details they agreed on a broad outline of events. There was a blazing sun, a river trip up the Thames and then a picnic during which Carroll created a fictional elsewhere for his “dream-child” Alice to explore. Wonderland came into existence as an adventure playground for the imagination.

The truth may have been rather different. Official meteorological reports record the day’s weather as dreary rather than dreamy: “cool and rather wet”, with total cloud cover and a maximum temperature of 19.9C. But facts were less powerful than the tug of fiction, especially when it became clear that the Oxfordshire riverbank had been the scene of a modern creation myth, and soon the memories of everyone present had been gilded and polished until they shone. The shifting moods of real life were replaced by an afternoon of permanent sunshine.

Retracing the boat trip today is like a journey back in time. The first thing that strikes a modern passenger is how fit Carroll and his rowing partner Robinson Duckworth must have been. It takes a pleasure boat at least 30 minutes to putter upriver to Godstow, sliding through water that is as green as turtle soup, and rowing against the current can take two hours or more. The first part of the journey is visibly hemmed in by modern life, thanks to a concrete ribbon of embankments and an architectural patchwork of housing developments, but soon the river returns to a more unchanging landscape. Willows bend overhead; rabbits lollop comically in the undergrowth; occasionally there is the metallic flash of a kingfisher. A few hundred yards beyond Osney Lock, the river passes by Port Meadow, a bleakly beautiful expanse of grassland where cattle and horses have grazed for centuries. A few distant church towers peep over the treetops, but otherwise it is easy to feel geographically and historically dislocated from the rest of Oxford.

After the party reached Godstow, the Liddell girls demanded a story, and in drawing inspiration from his surroundings Carroll could have chosen from many different narrative scenarios. He could have anticipated Charles Kingsley’s The Water-Babies, which would begin its serialisation the following month, by making a fictional Alice frolic underwater with assorted river creatures. Looking further ahead, he could have drawn on the riverbank’s wildlife to create a different kind of underground adventure, as Kenneth Grahame would later do in The Wind in the Willows. Instead he decided to send Alice “straight down a rabbit hole”, although he later confessed that he did not have “the least idea what was to happen afterwards”.

The first thing that happens is a pun – appropriately from a writer who treated language as his personal plaything: as Alice falls slowly down a “very deep well” she is falling asleep. As she continues to tumble, she passes cupboards and bookshelves on which fragments from her waking life are stored, such as a jar labelled “ORANGE MARMALADE”, and gradually it becomes clear what kind of adventure awaits her in Wonderland. It is one that will take the contents of Alice Liddell’s head and mix them together until they are transformed.

Many of the scenes that follow also include fragments of Carroll’s memory. He had long enjoyed assembling homemade magazines, and several of Wonderland’s inhabitants are refugees from his earlier writings. The Dormouse, for example, who tells a “long tale” that snakes away to nothing, is a close fictional relative of the dog Carroll had drawn as a boy, with a “tail of desperate length” straggling limply across the page. The endless tea party is like a set of variations on another childhood drawing, this one showing a man staring fixedly at a clock – the joke being that a clock in a picture always looks as if it has stopped.

At the same time, Carroll’s decision to send Alice below the earth’s surface ensured his story was fully up to date. By 1862, few literary environments were as crowded as the underground. Carroll’s most obvious models were the traditional folk tales in which it was the location of Fairyland, a secret world that was usually entered not by falling down a burrow but by braving the damp and dark of a barrow, one of the ancient mounds of earth that pimpled the landscape and housed the bones of the dead. Dante’s Inferno was another possible influence, producing creatures such as the Hatter and his friends, who are like comic versions of the souls doomed to spend eternity stuck in the same punitive loops of behaviour. Modern science fiction provided Carroll with a more recent set of narratives to play with, because plots in which characters discovered strange new civilisations underground were becoming increasingly popular – hence Jules Verne’s decision two years later to send his explorers journeying to the centre of the Earth.

Even without these literary associations, the underworld was a place to which the Victorians increasingly enjoyed making mental excursions. The Earth’s surface was being reconceived as a skin that was tightly stretched over the veins of communication and arteries of power that kept modern life moving – in 1862 the world’s first underground line was close to completion after years of construction that had left ragged scars across London – and what lay beneath was a place where stories germinated in the dark like mushrooms. Above ground might have been where most people spent their lives, but as John Hollingshead observed in his 1862 work Underground London, it was in a civilisation’s subways and hiding places that the imagination could “run wild” and indulge in a “passion for dreaming”.

When Carroll completed the first manuscript version of his story, which he presented to Alice Liddell in 1864, he gave it the title Alice’s Adventures Under Ground. Simultaneously he was expanding it into the more familiar version he published in 1865, in which he altered “Under” to “Wonder” and “Ground” to “land”. Carroll’s title has since become so well known that it slips off the tongue without any thought, but at the time it was an unusual choice. Alice often “wonders”, but never names the place she enters in her dream, and nor do any of the creatures who live there. It is only her older sister, on the final page of the story, who thinks of it as Wonderland.

Perhaps the book she is reading on the riverbank is supposed to be one of the earlier attempts to locate this enchanted country. If so, she would have had a small library of examples to choose from. It was an idea firmly rooted in Romanticism. For German writers such as Friedrich Schiller or Joseph Freiherr von Eichendorff, whose poems “In fernem Wunderland” (“In a Distant Wonderland”) and “Ein Wunderland” (“A Wonderland”) were often translated and anthologised in the period, Wunderland referred to a place where anything could happen because it existed only in the imagination. The same idea also attracted English and American authors. In Sartor Resartus, Thomas Carlyle had referred to “Fantasy” as a “mystic wonder-land”, and the word was frequently applied to areas of life that could not be explained by reason alone. In John William Jackson’s poem “My Lady-Love”, an angel’s voice is heard singing “A mystic melody from wonder-land”, while Carlyle himself had been praised for making “the old dead past a new and beautiful, and living Wonder-land”.

If Carroll had a specific source in mind, however, it was probably a poem published by FT Palgrave in his 1854 collection Idyls and Songs. It is rarely read today, but Palgrave was well known in Oxford, where he was a fellow of Exeter College and later professor of poetry. His book had already attracted the attention of Carroll, who noted that its poems “chiefly on children” included a sonnet addressed to Agnes Weld, a girl he would later photograph as Little Red Riding-Hood. But the poem that seems to have particularly snagged on his memory was “The Age of Innocence”.

It opens with a burst of praise for a child named Alice: “On little Alice late one morn I gazed, / Darling of many hearts, half risen from sleep … ” There follows a long description of another girl, whom the speaker eagerly watches as she plays, asking himself “What fancy lodges in thy breast?” She clasps his knee and asks for “A fairy tale”, and he agrees in exchange for a kiss (“There’s nothing gain’d on earth for nought”), although he confesses that he tried to read the book earlier and was unable to “re-awake the spell”. With a child beside him, however, he can unlock the secret magic of the story, and more importantly the buried power of his own imagination: “That wonder-land once more I see – / Once more I am a child in Thee”. Parts of Palgrave’s description are disconcertingly physical, as he dwells on the girl’s “sock turn’d down – the ancle fine – / The wavy folds – the bosom line”, but his conscious intention is clear. The imagination of his “little wonderer” is a passport back to a state of innocent creativity. “Wonder-land” represents paradise regained.

Not all modern readers are convinced that Carroll was equally innocent. In Wonderland, the Knave of Hearts is accused of stealing some tarts – a crime that in a nursery rhyme is as unavoidable as rhyme itself – and the King mutters selected phrases of the evidence to himself: “We know it to be true” … “If she should push the matter on” … “What would become of you?” Some of Carroll’s Christ Church colleagues might have had similar thoughts about his friendship with the Dean’s daughter. On the other hand, the Queen’s conclusion, “Sentence first – verdict afterwards”, is a joke that recognises how the court of public opinion might treat accusations that are considerably more serious than tart-theft. It is far easier to condemn Carroll than it is to decide exactly what he should be accused of.

He sometimes worried that a child’s imagination might be equally vulnerable to the more troubling aspects of life. Even Alice repeatedly finds herself being threatened by her own dream. Almost all the creatures she meets are cranky rather than cuddly, from a young crab that talks “snappishly” to a mouse that “growls”. In addition to the dangers of execution or being “snuffed out like a candle”, Alice at various times risks breaking her neck against a ceiling, being trampled under the feet of a giant puppy and having her toes trodden on. Although her dream occurs on a riverbank, Wonderland turns out to be more like the “entangled bank” at the end of Darwin’s Origin of Species, where “forms most beautiful and most wonderful” are engaged in an endless “Struggle for Life”. Even the “good-natured” Cheshire Cat has “very long claws and a great many teeth”, while Alice ends her dream with a violent display of temper. There is more than an element of truth in Carroll’s sly joke to one young reader that his story “was about ‘malice’”.

Yet none of that stopped Carroll from thinking of Wonderland as a hazy mixture of fairyland and heaven. It was a place that welcomed people of all ages, but only if they followed the biblical injunction to become as little children, by agreeing to see life through Alice’s eyes. Only in this way could they join her in glimpsing “bright flowers” and “cool fountains” at the end of a dark passage, and then shrink even smaller to enter “the loveliest garden you ever saw”. Only in this way could they share in her discovery that Wonderland was not a place but a state of mind.

Alice Liddell soon outgrew the miniature world Carroll had created for her. On 11 May 1865, a fortnight before he received a specimen copy of his book from the publisher Macmillan, Carroll confided to his diary that “Alice seems changed a good deal, and hardly for the better,” adding that she was “probably going through the usual awkward stage of transition”, ie puberty. Whether it was more awkward for him or her he did not say. The fictional Alice, on the other hand, was a girl he could keep close without any fear of her leaving him behind. As with his photographs, his stories were sealed environments in which little girls could stay little.

Over the next 30 years, Carroll experimented with this idea in various ways. At the end of 1871, he published Through the Looking-Glass, a sequel he privately referred to as “Alice II”, in which he proved that time could be manipulated much more effectively on paper than it could in real life. The fictional Alice was now seven and a half, as she tells Humpty Dumpty, meaning that in the six years that had passed since her last appearance, she had aged only six months. Some of Carroll’s other versions of the story involved equally ambitious attempts to slow down time’s arrow or make it loop back on itself. In 1886, he collaborated on a theatrical version, which brought Alice to life on the stage, but also allowed her to be replaced whenever she grew too old. In 1890, he produced a large-format picture book for young children, The Nursery “Alice”, which meant that Alice looked physically bigger, but only because the length of her story had been drastically reduced.

Carroll was not alone in wondering whether his heroine would always remain the same. One of Alice’s initial fears in Wonderland is that she has been replaced by a doppelganger, as she thinks over “all the children she knew that were of the same age as herself, to see if she could have been changed for any of them”. In the years after Carroll’s death, this started to look uncannily like a premonition. His original stories continued to be the standard against which all successors would be measured, but alongside the original Alice there was now a growing army of Alice-alikes.

Carroll’s fictional world was also starting to lose its identity. Already any clear distinction between the two Alice books had started to dissolve, and Wonderland was widely assumed to include both territories, forming a Greater Wonderland, or Onederland, in the public imagination. Soon it had spawned a whole galaxy of literary rivals, as modern Alices busied themselves exploring Blunderland, Pictureland, Merryland, Emblemland, Monsterland, Motorland, Thunderland, Plunderland, Rainbowland, Justnowland, and, in a rare concession to realism, Cambridge.

By the start of the 20th century, “Wonderland” had become a piece of cultural shorthand for any part of the real world that seemed enchantingly strange, as travel books introduced readers to The Eastern Wonderland or The Wonderland of the Pacific. Some spiritualists tried to argue that ghosts were drifting around in a posthumous Wonderland of their own. Even Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, who published a set of photographs in 1920 of two girls from the Yorkshire village of Cottingley, alongside what they claimed were frolicking fairies, felt the need to rename one of the girls Alice, as if the real Wonderland was the invisible world that surrounded us every day. Increasingly, Carroll’s book was much more than a book for thinking about: it was a book for thinking with.

This wasn’t always a cheerfully optimistic process. Alice’s Wonderland often resembles a dream that is on the verge of toppling over into a nightmare, so perhaps it isn’t surprising that it became a popular reference point during the first world war. As early as December 1915, a regimental magazine was describing the snaking maze of trenches outside Ypres as “a sad, enchanted region” in which bullets and shells turned the air into a soundscape as clotted as Carroll’s poem “Jabberwocky”, where slithy toves gyred and mome raths outgrabe. And a decade after the end of the war, writers were still using Carroll’s story to make sense of events that more often resembled savage nonsense.

RC Sherriff’s 1928 play Journey’s End provides a powerful example. For most of the action, the Alice books remain in the background, like the steady grumbling of the guns; only occasionally do they flare into life to remind the audience that they have been there all along. The night before a planned raid on the German lines, the officer Osborne takes a small leather-bound copy of the story from his pocket and starts to read. Initially it appears to be straightforward escapism, rather as he proposes that they avoid thinking about the busy worms in their trench by talking about croquet instead. (The Alice books would fulfil a similar function in the 1942 film Mrs Miniver, where a mother recites Carroll’s line about “remembering her own child-life and the happy summer days” as her family listens to the muffled thump of bombs falling during the blitz.) Yet as Journey’s End grinds on to its inevitable conclusion, it becomes clear that nobody fighting on the front line really needs to read Carroll’s story. They are already living out a version of its mad logic.

Much of what happens in the shelter involves a distorted version of Carroll’s writing, from the need to include plenty of pepper in the soup (“It’s a disinfectant”), to the list of objects that Osborne recites (“Of shoes – and ships – and sealing wax – / And cabbages – and kings”), which later returns in a mutilated form when a British soldier searches the pockets of a young captured German and discovers “bit of string … little box o’ fruit drops; pocket-knife … bit o’ cedar pencil … and a stick o’ chocolate”. Soon a second soldier is wounded by shrapnel, and whispers his final line “It’s – it’s so frightfully dark and cold”. Within a minute the shelling rises in intensity and the shelter’s timber props cave in. It turns out that not all underground adventures have a happy ending.

By 1928 the theatre had a modern rival, cinema, and here Carroll’s story also played a prominent role in showing what might be possible. The first edition of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland already contained a primitive version of moving pictures, because the two illustrations that showed the Cheshire Cat fading to an enigmatic grin were printed on consecutive pages, allowing a reader to make the Cat materialise or dematerialise by flicking the first page back and forth.

Within a few years technology had caught up with Carroll’s imagination. The Wonderland music hall in Stepney was just one of the venues that were converted into cinemas, and by 1915 three silent versions of Carroll’s story had offered viewers the chance to see “real” versions of Alice moving jerkily across a screen. Yet while these films attempted to flesh out Carroll’s narrative with human actors, the most successful adaptations took a different approach.

When Walt Disney arrived in Los Angeles in August 1923, he was holding a cheap suitcase that contained an equally cheap suit, a sweater, some drawing materials, $40 and Alice’s Wonderland, a 12-and-a-half-minute reel of film mixing live action and animation, in which a ringletted four‑year-old named Virginia Davis explored Cartoonland. Between Alice’s Day at the Sea in 1924 and Alice in the Big League in 1927, the Disney brothers produced a total of 56 “Alice Comedies”, and slowly the future direction of their newly formed studio became clear. As the screen time of the real Alice was gradually reduced, so Cartoonland was taken over by Disney’s anthropomorphic animals. It turned out that the jokes were better when people weren’t getting in the way.

In 1926, a book on nonsense poetry had suggested that “The realm of Nonsense is not so much Fairyland as Dreamland”, where “the memories of the day are twisted into many queer and unexpected shapes by the imaginations of the night”. Carroll had already shown how this could produce stories on the page; now Disney invited spectators to enjoy a contemporary alternative. Watching a cartoon was another way of dreaming while remaining awake.

By the time of Alice Liddell’s death in 1934, her fictional alter ego was busier than ever. That year saw the release of Betty in Blunderland, in which a saucer-eyed Betty Boop passed through a mirror to meet manically inventive cartoon versions of Carroll’s characters, and also Babes in Toyland, in which Laurel and Hardy, as “Stanley Dum” and “Ollie Dee”, encountered the actor (Charlotte Henry) who had starred as Alice the previous year in a major Paramount film.

Meanwhile, psychoanalytical critics were starting to wonder if Alice’s rabbit hole wasn’t only a rabbit hole. (William Empson reportedly told IA Richards “There are things in Alice that would give Freud the creeps”.) While this alarmed many readers, it also created a new layer of the story for writers such as James Joyce to burrow into. That is why his own dream vision, Finnegans Wake, included so many versions of Carroll and his characters, who repeatedly rise to the surface of the text before sinking back into a bubbling melting pot of words: “Wonderlawn’s lost us for ever”, “knives of hearts”, “from tweedledeedumms down to twiddledeedees”, and many similar “loose carolleries”. It reminded readers that language was a jigsaw puzzle with an infinite number of solutions.

Since then, Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland has taken on a dizzying variety of new forms, including toys, comics, fan fiction, computer games and pornography. Many of these have been created online, turning the computer screen into a modern looking glass through which it is possible to explore an entirely new WWWonderland. Yet reading the book remains the best way of exploring its full creative range. And this is because Wonderland is an imaginary universe that is still expanding.

Not only has Carroll’s story proven to be infinitely elastic since 1865, happily accommodating cultural changes from the suffragette movement to mushrooming drug use; it also grows up with us as individuals. It reminds us that the Caterpillar’s question “Who are you?” is one that we are unlikely to be able to answer any better than Alice.

Francis Spufford once suggested that the pleasure of reading stories in childhood that begin in the real world, and then take you somewhere else, is that “once opened, the door would never entirely shut behind you”. The door into Wonderland works like that. Wonderland may exist only in Alice’s head, but once we have visited it in her company it exists in our heads, too. And because this door never altogether shuts behind us, after we return to the life that exists outside books it never seems quite the same again.

- Robert Douglas-Fairhurst’s The Story of Alice is published by Harvill Secker.