Why I’d Like to Stop Talking About Learning Styles

Posted by admin on

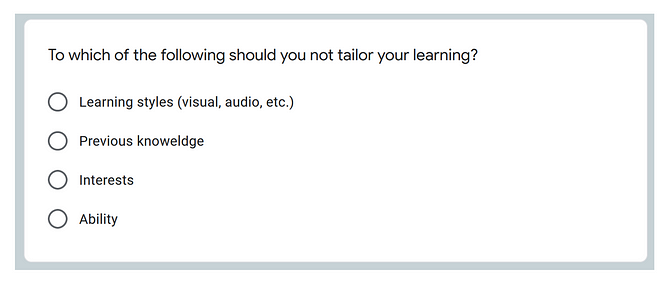

In workshops I offer on the science of learning, I often ask participants to take a short online quiz based on one developed by Ulrich Boser. The quiz focuses on common myths and misconceptions around learning. One of the questions asks “To which of the following should you NOT tailor your learning?

The correct answer here is the first choice. We should NOT be tailoring our teaching and learning around students’ so-called learning styles.

[this is where I pause, duck under the table, or behind my Zoom screen and wait for the barrage of tomatoes…]

Let’s look at the other options: Students’ prior knowledge, interests, and ability are all important things to consider when designing learning environments and experiences. We also need to make sure students feel comfortable emotionally and that they belong and are welcome in the learning environment. We need to identify and address barriers to student motivation, minimize distractions, and eliminate things that can cause extraneous cognitive load. And even when we’ve attended to these things (no small feat), we can’t be sure that students are processing the information we are teaching in the way we would like, what exactly they are thinking about, or what connections they are making. But it’s a start.

In his research, Boser found that 90% of respondents thought students should receive instruction tailored to their own “learning style”. This is not particularly surprising. The idea that students have different learning styles, such as auditory or kinesthetic, is a tenacious myth, and one not supported by research evidence.

When I plan my workshops, I often hesitate and consider not talking about learning styles. Maybe I should just leave it alone and instead focus on “safer” topics such as encouraging students to write their own notes, or quiz themselves using flashcards (both of which are effective, evidence-based learning strategies).

Just as one avoids discussions of politics, and religion and other topics at a dinner party, I have been “conditioned” in a way not to want to bring up the topic of learning styles.

It’s a subject about which people feel extremely passionate, and it tends to stir up sometimes contentious, polarizing debates which can derail otherwise productive discussions about learning.

Recently I’ve been wondering why…

- One possibility relates to the “trophy culture” idea. If we all have different learning styles then surely that means if only we were taught in that style, we would all be able to succeed at everything? If we don’t do well on a test or in a particular class, it’s easy, after the fact to say “well, I didn’t do so well because I’m more of a visual person than a numbers person.” It’s a non-falsifiable statement and one which can serve to make us feel better about our poor performance.

- Or perhaps it’s because we have a tendency to want to do things we feel are easier. Or that we enjoy doing. This is why students like to study in ways that made them feel good (like highlighting or re-reading passages). They develop a sense of fluency and ease of recognition which tricks them into thinking they know something. But only when you actually try to recall something do you know if you really know it. And that’s harder. And may make you feel as if you’re not making as much progress. When you’re learning something new, it can be demoralizing to feel that you are stagnating, or not improving as fast as you would like. Even more so if you don’t understand that when you’re new at something the learning curve is steep — but an essential part of the process.

- We all have experience with teaching (in some form or another) which can make us feel as we have some level of expertise in the area. As Boser puts it, we have a “Been there, done that” problem. Most of us went to school, and have a feeling we know what good teaching looks like. As a result, we are keen to opine on the quality and effectiveness of the latest educational approach.

You don’t need to look that hard to find scores of well-renowned, knowledgeable educators and scholars working to shine a light on the paucity of evidence about matching instruction to learning styles.

In 2017, for instance, a group of thirty eminent academics from the worlds of neuroscience, education, and psychology sent a letter to the British newspaper The Guardian voicing concern about the popularity of the learning style approach among some teachers.

Others have conducted in-depth studies of the literature in search of well-designed studies showing clear evidence of a connection between instruction tailored to learning styles and differences in student outcomes.

Spoiler alert — they found “no adequate evidence base to justify incorporating learning-styles assessments into general educational practice.”

The idea of learning styles may be appealing because it is intuitive. Just as height, or head and foot size, eye color and shape vary, so do people vary in their abilities.

People are better at some things than others. It’s true.

Some people have an uncanny ability to remember faces, or to hear a piece of music and play it immediately, or be skilled at hand-eye coordination. Yes, we’re different, and we have certain preferences, but that doesn’t mean that the way we actually learn is better depending on the modality of instruction.

Let’s think about this: If I want to teach someone how to make a new kind of soufflé, what’s the best way to do it?

It depends!

I need to know things like:

- Have they ever made a soufflé before?

- Do they know how to separate egg whites from egg yolks?

- Do they know how to make a water bath in the oven?

- Do they know how to use a whisk and how to tell when the whites have been whisked just enough?

And so on.

For a complete novice, a video, and in-person demonstration, some step-by-step, scaffolded practice would likely be needed.

For a pro, I could probably hand them a printed recipe with the ‘innovative’ part highlighted, and off they’d go.

I am not teaching them based on any sort of stated ‘style’. I’m meeting them where they are and teaching them from the beginning or letting them apply their prior knowledge and experience.

Is this simply a matter of semantics? Is it really dangerous or damaging to keep this myth of learning styles alive? Does it really matter if some people feel that they have a “visual learning style?”

It does matter and here are some reasons why:

Opportunity costs: It does not make sense to pour resources, time, and effort into a framework of teaching and learning that is not substantiated by evidence. As educators, we need to think like scientists; consider the available evidence, and tailor our teaching and learning practices around that. Rather than wasting time trying to accommodate our teaching practice around learning styles, we should look to the preponderance of evidence for things that CAN positively impact learning. And there are many. Every moment of teaching training or professional development spent on figuring out ways to tailor instruction to students’ individual learning styles is an opportunity lost to help support the development and implementation of evidence-based practices.

Growth mindset: As well as costs in terms of time and money, another reason the notion of learning styles is risky is it creates the belief that certain students are unable to learn because the material or mode of instruction is inappropriate for them. Talk about slamming the brakes on the idea of ‘growth mindset’ (which interestingly, does not suffer the same issues as ‘learning styles’).

If we tell students they can only learn in a certain way, they may develop a more rigid perception of learning. Humans have a tremendous capacity to adapt, change, and grow. It matters, therefore, for students to believe they have the ability to grow and learn and are expected to do so. Without that belief, students may lack the motivation to put in the mental effort and perseverance required to learn something new or get better at something. Learning is hard and we do a disservice to students if we let them believe otherwise. Or give them an ‘excuse’ to give up on something they find more difficult.

Square Peg/Round Hole: Imagine the student who is told they are a visual learner. They may try and process new content in the mode of their “learning style” even if the style does not fit the particular task. This is an incredibly inefficient way to learn.

Policy and practice reform: Misconceptions and myths about learning can impede school reform efforts. If a large percentage of people cling to beliefs on the efficacy of a learning styles approach, they are less likely to support initiatives that oppose it. Boser used the analogy of climate change to illustrate this point. Skepticism around climate change serves only to slow down meaningful policy action — even though there is broad consensus that climate change is real and poses a real risk to the future of our planet.

When we discuss educational topics, it can seem, more so than in other fields, that everyone’s opinion of what works and doesn’t work is equally valid and that we don’t need to look at data and evidence of efficacy. Everyone has been to school and has many years on the receiving end of teaching (likely some good and some not so good).

We do not all, however, have the same experience with medical research, or quantum mechanics, violin playing, or architecture. Thus we may be more willing to accept it when experts arrive at a consensus that a certain medical technique for knee-replacement surgery is no longer valid, or that a certain type of bridge design is better than another for a particular climate.

In Think Again, Adam Grant wrote: “Scientific thinking favors humility over pride, doubt over uncertainty, curiosity over closure.” If we believe we have already found the truth then we stop searching for or recognizing gaps in our knowledge. Grant uses the term “idea cults” for those who “preach the merits of their pet concept and ‘prosecute’ anyone who calls for nuance or complexity.”

A laudable educational goal is to help make students better consumers of information. Equally so is the need to make teachers and teacher-training programs “critical consumers of scientific research”. To normalize the practice of evaluating research evidence. Surely this should trump the status quo of relying on personal beliefs and experiences and what makes us ‘feel good’?

My hope is that soon I can stop worrying about engaging in fruitless discussions about learning styles; not only because we have wealth of excellent, reliable, robust research on what DOES work for learning, but because people know about it. That we, in whatever role we play, will be open to evidence that calls into question existing beliefs and allows us to recognize gaps in our knowledge.

Acknowledging the difference in stakes, debating this issue seems as pointless as debating topics like climate change or the efficacy of vaccines.

I’d rather be proactive than reactive.

I’d rather focus my efforts on helping others recognize and implement effective, lasting, motivating, active, research-based forms of teaching and learning which promote long-term meaningful learning for all students.

—

Previously Published on Medium

iStock image

The post Why I’d Like to Stop Talking About Learning Styles appeared first on The Good Men Project.