The Metrics for Easing COVID Restrictions Don’t Exist

Posted by admin on

When many states and cities implemented shutdown orders to combat the spread of the coronavirus last year, an array of metrics told the public when, or if, the closures would end. Restrictions on shopping, dining indoors, playing sports, and going to school were created based on specific data such as the COVID-19 positivity rate and the number of cases.

In New York City, elaborate, color-coded zones were concocted for neighborhoods, introducing certain restrictions tied to the prevalence of COVID. Another tiered, color-coded system was used in California, bound to cases per every 100,000 people and positivity rates. The idea was simple: If certain numbers diminished, rules could be relaxed.

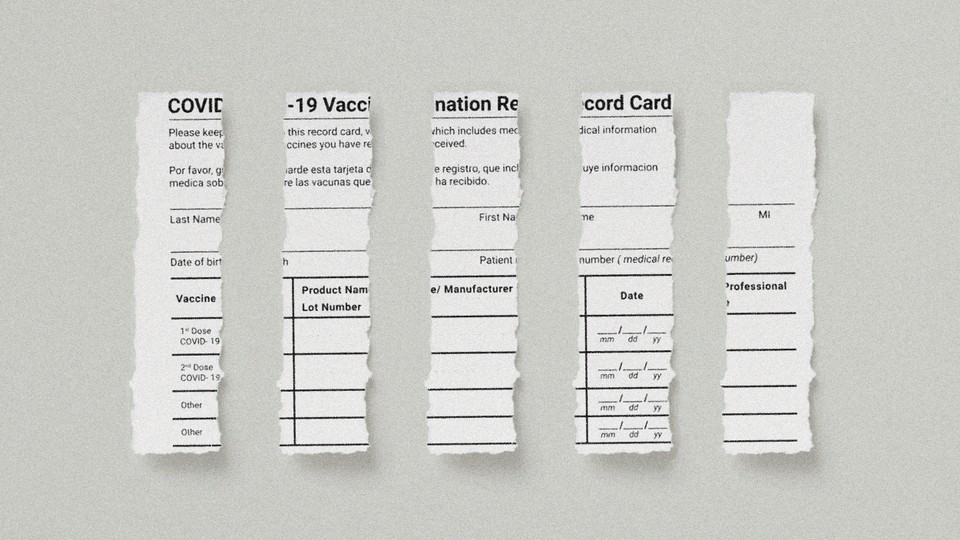

But most of the newest mandates carry no such metrics. In a select number of large cities, such as San Francisco, Los Angeles, New Orleans, and New York City, proof of vaccination is or will be required for most indoor activities, including dining, going to the gym, attending a movie, and hanging out at a nightclub. Localities have implemented these mandates without explaining when they will be lifted, or if they ever will be. Case numbers, positivity rates, and hospitalizations have not been invoked. For now, these policies are effectively indefinite. Other cities, including Chicago and Boston, have discussed such mandates but have yet to implement them.

[Read: Why Biden bet it all on mandates]

Given what we know about COVID—indoor spread is far more likely than outdoor spread, and eating and drinking are easy ways to pass along the virus—vaccine mandates make plenty of sense. As terrifying as the Delta wave has been, all three vaccines authorized in the United States have proved remarkably resilient against the variant. Making vaccine status a condition of entering certain public spaces does run the risk of creating a two-tiered society, with the more affluent vaccinated and the poorer unvaccinated, but it has encouraged more and more people to sign up for doses. More than 70 percent of New York City residents, for example, have now received at least one dose of a vaccine.

The question, though, is how long such mandates will persist, and on which data they will be based. Will certain cities maintain vaccine requirements well into next year? Or longer? Will a new normal arise, with future generations learning to always flash their vaccine card or pass at bouncers and bartenders, like airline passengers have accepted removing their shoes and belt in a display of security theater 20 years after 9/11?

“It’s logical to assume that any policy like that isn’t forever, but it’s also very difficult to know where things are going, what the twist and turns are going to be,” says Lynn Goldman, the dean of George Washington University’s Milken Institute School of Public Health. “Like a lot of other viruses and pathogens, the Delta variant may end up being replaced by a variant less lethal that works more like the common cold, and we may end up deciding we don’t need to continue to be vaccinated. Or there could be an evolution to the worse possible strains—we could end up with a strain worse than Delta. We can’t say that’s impossible.”

Though coronavirus cases are on the decline in most of America, following a still somewhat mysterious two-month surge, most public-health experts are reluctant to ascribe any kind of metric that could determine when vaccine mandates would be phased out. Much of this is tied to the uncertainty of Delta and future variants.

[Read: How the pandemic now ends]

Still, it’s a noted departure from every other pandemic phase, when people could follow case numbers or positivity rates and anticipate that mitigation measures promised a return to life as we once knew it. At least one other country chose to unwind mandates and restrictions when a certain level of vaccination was reached. In September, with more than 83 percent of the population ages 12 and older fully vaccinated, Denmark announced that proof of vaccination would no longer be required to enter indoor venues such as nightclubs.

In American cities with similar mandates, no such promises have been made. The New York City Health Department admitted that it had no timeline or data to point to that would determine when vaccine mandates for indoor activities would be lifted.

“Increasing vaccination rates will help us end the pandemic, and these mandates are a key part of this effort,” Michael Lanza, a health-department spokesperson, told me. “We will continue to monitor vaccination and transmission rates but do not currently have a threshold where we’d roll them back.”

The same is true in San Francisco, where Mayor London Breed recently drew condemnation for flaunting her government’s mask mandate inside a nightclub. “As we get more of our population vaccinated, we continue to monitor the data to measure the full effect of our current vaccine mandates and decide on next steps,” Noel Sanchez, a spokesperson for the San Francisco Department of Public Health, told me. “As it has been the case since the outset of the pandemic, we will be guided by science and, to the extent possible, will take a regional approach on our virus-mitigation strategies.”

San Francisco’s vaccine and mask mandates have a key difference, however. Health officials have announced that mask requirements will be eased on October 15, with the new rules tied to a stabilization or decline in hospitalizations and cases. In San Francisco County, at least 74 percent of the total population has been vaccinated.

What percentage of a population must be vaccinated before any kind of vaccine mandate is lifted? Public-health experts don’t quite agree on a number. Figures from 70 to 80 percent, or even higher, have been floated. Ali Mokdad, a professor of health-metrics sciences at the University of Washington, in Seattle, says he would like to see 80 to 85 percent of a population vaccinated before any sort of existing restrictions are lifted. Arguing that a winter uptick in coronavirus cases is still possible, he told me that vaccine mandates for indoor, public venues should remain in place until at least the spring.

“I don’t see a way for any location to dial back until next year,” Mokdad said. “This is a new virus. We’re learning about it as we go.”

The goal, public-health experts say, is reaching the point where hospitals are never overwhelmed with coronavirus patients again.

“My hope is we get to a place where, through vaccination coverage and through infections of the unvaccinated, we have a high level of protection against hospitalization,” Denis Nash, an epidemiologist at the City University of New York, told me. “At some point we have to move on, right?”

[Yasmin Tayag: Stop calling it a ‘pandemic of the unvaccinated’]

It’s reasonable to ask, as 2021 draws to a close: When will that be? Unlike in previous phases of the pandemic, public-health officials, politicians, and even members of the media seem to have little will to explain to millions of people what normalcy might look like. This is understandable for the time being. In the past, localities have relaxed various shutdowns and mandates, only to encounter a new wave of the coronavirus. No one wants to take another gamble and lose.

Yet all pandemics end. Viruses lose their potency and society reorders itself. Unlike the flu pandemic of a century ago, which killed a far higher percentage of Americans, vaccines now exist to save lives. Despite the, rightfully earned, general pessimism about the national response to COVID, more and more Americans are getting vaccinated every day.

Academics, public-health journalists, and epidemiologists are always going to be more cautious than the general public. This makes sense. They are the ones scrutinizing data, studying trends, and analyzing numbers for context. They are trained to do this, to behave in such a way that risk is minimized. Mandates and restrictions may not burden them so much. Some want social distancing to continue well into the future; others want booster shots to eventually be a condition for “full vaccination.”

A time might come, however, when the demands for ongoing restrictions no longer match the reality of the coronavirus in America—and if no significant winter surge materializes, that time might not be too far off. Metrics matter because they tell us what is in front of us (and what is behind us), and they offer a path forward. We need to start talking about what that path might look like, and what it will take to get there.