Silence Of The iPods: Reflecting On The Ever-Shifting Landscape Of Personal Media Consumption

Posted by admin on

On October 23rd of 2001, the first Apple iPod was launched. It wasn’t the first Personal Media Player (PMP), but as with many things Apple the iPod would go on to provide the benchmark for what a PMP should do, as well as what they should look like. While few today remember the PMP trailblazers like Diamond’s Rio devices, it’s hard to find anyone who doesn’t know what an ‘iPod’ is.

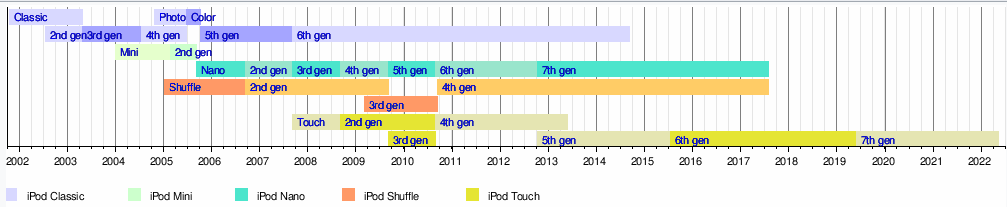

Even as Microsoft, Sony and others tried to steal the PMP crown, the iPod remained the irrefutable market leader, all the while gaining more and more features such as video playback and a touch display. Yet despite this success, in 2017 Apple discontinued its audio-only iPods (Nano and Shuffle), and as of May 10th, 2022, the Apple iPod Touch was discontinued. This marks the end of Apple’s foray into the PMP market, and makes one wonder whether the PMP market of the late 90s is gone, or maybe just has transformed into something else.

After all, with everyone and their pet hamster having a smartphone nowadays, what need is there for a portable device that can ‘only’ play back audio and perhaps video?

Setting The Scene

The concept of portable media players isn’t a new one by any stretch of the imagination. From portable record players in the 1950s alongside the rise of compact, transistor-based radios in the 1960s and of course ever more convenient media formats like the 8-track tape, Philips Compact Cassette and the Compact Disc (CD) that made media more portable.

When Sony launched its first Walkman in July of 1979, it would kickstart a whole new market of portable media devices. With over an hour of music on a single cassette, anyone could listen to their favorite music (and mix- tapes) while traveling, working out at the gym, or jogging through the park or along the beach in a typical 1980s fashion. Even if one’s personal use of a Walkman – or one of its many clones – was less glamorous, it is hard to deny the cultural change that came with the availability of these devices.

Naturally, technological progress is inevitable. That’s why eventually cassette-based portable audio players gave way to CD-based ones. After details like anti-shock buffering were figured out to (mostly) prevent audio skipping, everyone needed to have personal CD-quality audio in their lives. Yet for all their benefits, optical media like CDs are less durable and more prone to technical issues than tape-based media, not to mention that CD-based Walkman players and clones are far less pocketable than their tape-based siblings. This meant that the tape-based Walkman and kin remained around until the early 2000s.

Things got interesting during the 1990s, as in 1992, Sony had already released its MiniDisc format. Despite this still being optical media (magneto-optical to be precise), MD media is far more compact than a CD, stores at least as much audio as a CD and comes in a protective cartridge. Although MD became affordable enough for the average consumers by the end of the 1990s, it saw its commercial success hampered by a number of things, not the least was Sony’s proprietary ATRAC audio format that was required for MD audio.

The other major obstacle for MD was a newfangled audio format that was doing the rounds on the Internet’s Digital Information Super-Highway, called MP3, which got pounced upon by then multimedia giant Diamond with the release of the Diamond Rio PMP300 Flash-based MP3 player in 1998 (also reviewed by LGR and Ars Technica in 2016). While not exactly a multimedia star by 2022 standards with its clunky, parallel port-based PC connection, for something that was meant to be used alongside Windows 98, it has essentially the same features as the first Apple iPod that would be released three years later, including internal storage, media controls, an accompanying software utility and (eventually) an online music store.

Enter The Pod

The main goal of Apple when it created the iPod was to apply its sense of style and user-interaction to it, as covered in an article by Wired from 2006 featuring interviews with people who were involved with the development of iPod and the accompanying iTunes software. The latter was originally called SoundJam when Apple bought it along with hiring its main programmer: Jeff Robbin. Originally iTunes was meant to provide a solid music player for MacOS to match the digital music revolution that erupted during the late 90s, but would end being the management software for the iPod as well.

The iPod was developed as a result of a search for new gadgets that might fit in the rapidly developing multimedia ecosystem of that time. As Greg Joswiak – Apple’s vice president of iPod product marketing – put it, while they found that products like digital cameras and camcorders were quite decent, the user interfaces and handling of PMPs of the time ‘stank’. They were either big and clunky or small and rather useless, with often small 32 MB or 64 MB built-in memory due to the limitations of Flash memory.

Who exactly pitched the idea of creating a music player is not known, but when the idea came across CEO Steve Jobs, he immediately jumped on it, leading to the development of the first prototypes. The next question thus became what this ‘iPod’ – as it later became known – would have in terms of features that would make it better than the competition. Storage was a main one, and like some of the competing PMPs, the iPod would feature a hard disk drive (HDD), but not the rather large 2.5″ HDDs others were using.

The first-generation iPod used a then newly developed 1.8″ HDD by Toshiba. This gave it a roomy 5 GB – 10 GB of storage, and instead of the sluggish USB 1.1 connections of competing PMPs, it was equipped with FireWire. At 400 Mb/s (half-duplex), it was a much better match for the internal storage relative to the 12 Mb/s of USB 1.1. This advantage would remain until USB 2.0 and beyond became commonplace.

The iPod’s name was pitched by Vinnie Chieco – part of a team tasked with marketing the new device – as an allusion to 2001: A Space Odyssey and the illustrious “Open the pod bay door, Hal!” scene, with pods being the small vessels for missions outside of the spaceship.

Perhaps the only thing that the first generation iPod could be dinged on was the lack of Windows compatibility. You needed a FireWire-capable Mac system with iTunes on it to manage the contents of the device.

They Grow Up So Fast

The success of the iPod – or iPod Classic as it’d be renamed by its 6th iteration – would lead to another five revisions of the original model. Most notable change with the first revision (iPod Classic 2nd generation) included Windows compatibility, with the iPod’s HDD formatted with the HFS+ filesystem for use with Macs and FAT32 for Windows. Instead of iTunes, Windows users used Musicmatch Jukebox to manage the iPod.

With the 3rd generation iPod from 2003, USB support was added, with a capacitive control ring rather than the old mechanical scroll wheel and buttons. This release also dropped Musicmatch support and unleashed the joys of iTunes onto a Windows audience. With the 5th generation FireWire support was just for charging, while USB took over content synchronization duty, while a color display and video playback was a standard feature.

Alongside the ‘Classic’ range was a veritable flurry of new iPod models, including the Mini (based around the 1″ Microdrive), Nano (Mini-replacement, uses Flash storage), the display-less Shuffle, and finally in 2007 the first-generation iPod Touch. Whereas the former all were dedicated PMPs, the Touch could probably best be regarded as a phone-less iPhone. Featuring most of the same hardware as the iPhone, the iPod Touch runs iOS and can use the Apple App Store via WiFi.

End Of An Era?

If we regard the rise of the Walkman and similar devices as a response to the desire to listen to music that was purchased (as physical media, or digitally), then the shift to streaming music from subscription services over the past years would seem to be the driving force behind the purported demise of PMPs and the driving force behind Apple discontinuing the iPod. Whereas for years it made sense to have an ‘MP3 player’ to copy tracks to which were either purchased digitally, or ripped from purchased/borrowed CDs, there’s an ongoing shift towards paying for a subscription rather than purchasing music outright.

This change can be seen not just with Apple’s range of iPod players, but also with its refocusing from the iTunes Store to its streaming music business. The idea is not dissimilar to services such as Netflix and other streaming video services, with on-demand streaming of any content that is available on this service, rather than buying or borrowing albums, films and series.

Within this brave new world where nobody owns the music which they listen to, it could be argued that the role of PMPs is over, as any supported internet-enabled device can gain instant access to a massive library of content. All without the need to build up your own, personal media library. Simply get the app on your smartphone, smart TV, smart watch, or smart refrigerator and sign up for a subscription. Convenience at your very finger tips.

Yet this notion is not entirely supported by the statistics, with data from the US showing a rise in audio CD sales the past years. At this point music streaming services generate over half of the music industry’s revenue, with CD and vinyl sales making up around 11%. What this tells us is that the announced death of personal media libraries may be very much premature.

Not Just Nostalgia

As much as the music market has changed since the era of wax music cylinders, one constant has always been that there are different types of people, each with their own preferences in the way they enjoy music. Based on this notion alone it would seem outrageous to suggest that everyone will just be streaming their media content from online services to their iPhones, Android phones and gaggle of ‘smart’ devices.

The advantages of physical media should be obvious: you’re not limited to the streaming service’s media library, you get at least CD quality audio, and there’s no monthly fee to keep the media. It will also never vanish from your library at the whim of a publisher and you can lug it freely along to that cabin in the mountains with absolutely zero cell reception. Copy it onto a PMP and you get all that, but in a more compact format. Ideal for those long hiking trips and to prevent blood-curdling roaming data costs during vacations.

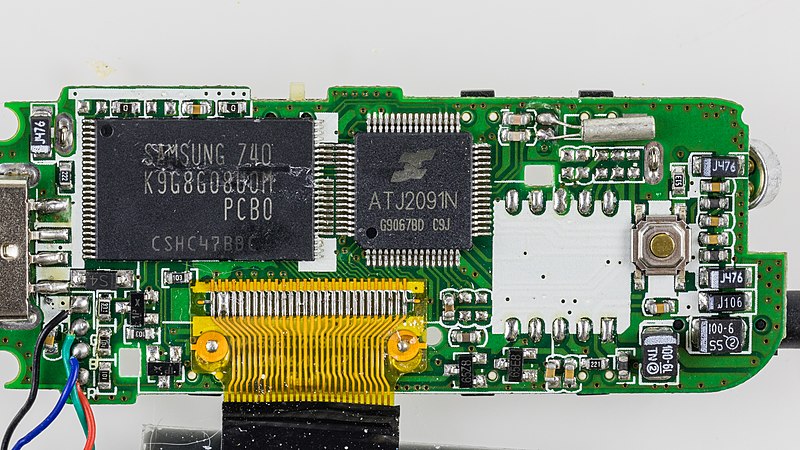

Using a dedicated PMP instead of one’s smartphone has the added advantage of saving battery charge, while adding physical control buttons that allow for tactile interaction. With today’s technology, a modern-day PMP doesn’t require more than a single processor chip in addition to a big NAND Flash chip (and/or SD card expansion) storage, all of which takes up little space and can last a long time on a single battery charge. Add to this not having to take out an expensive, fragile smartphone to fiddle with media controls on its touch screen and risk dropping it or having it stolen

Even so, splurging on the still existent modern-day PMPs (or ‘MP3 players’ as they are still colloquially referred to) isn’t a necessity, when open source projects like RockBox make it their mission to provide a wide range of older and newer PMPs – including the iPod – with updated firmware that even adds features absent from the original firmware.

We have also covered modifying and repairing iPods (and other PMPs) before, including upgrading the storage on an iPod Video as well as on an iPod Nano 3rd gen, and replacing the battery and storage on a 6th generation iPod. Unlike an average smartphone, these PMPs are fairly easy to repair and upgrade, adding another item to the list of potential benefits.

Good Vibes

Cheap portable tape players were a staple of the the 90s, and like so many I ended up with one of those. Even though they had the cheap tape mechanism which you wouldn’t want to waste anything better than a Type I tape on, as well as the cheap headphones with the foam that was guaranteed to disintegrate, it was still an awesome device. With it I could listen to music outside of the house, which was a rarity back then.

When the MP3-revolution came around, it changed all of that. It felt as if within a number of years things went from portable CD players – that’d skip if you so much as bumped the table it was carefully placed on – to Flash- and HDD-based players that would come each successive year in fancier styling and with ever more features packed in a smaller enclosures.

Even if I was never really a fan of the iPod-style ‘slab of aluminium/plastic’ aesthetic, I must admit to it being attractive devices in terms of their handling and ecosystem, especially with the iPod Nano and Shuffle. Having used one of the newer iPod Touch devices (as an iOS development device), I can however see why it didn’t make sense for Apple to keep selling it.

Even though Apple has said its farewells to the PMP market, this does not mean that this market is no longer. As we have seen, there are still solid reasons to keep using one of these dedicated playback devices, and even ignoring the diverse offerings of brand-new ‘MP3 players’ today, repairing and upgrading older players will ensure that those who want to keep using these devices can do so.

And who knows, maybe Apple will be back one day as the fickle music markets shift currents once again.