Publish or Perish: Data Storage and Civilization

Posted by admin on

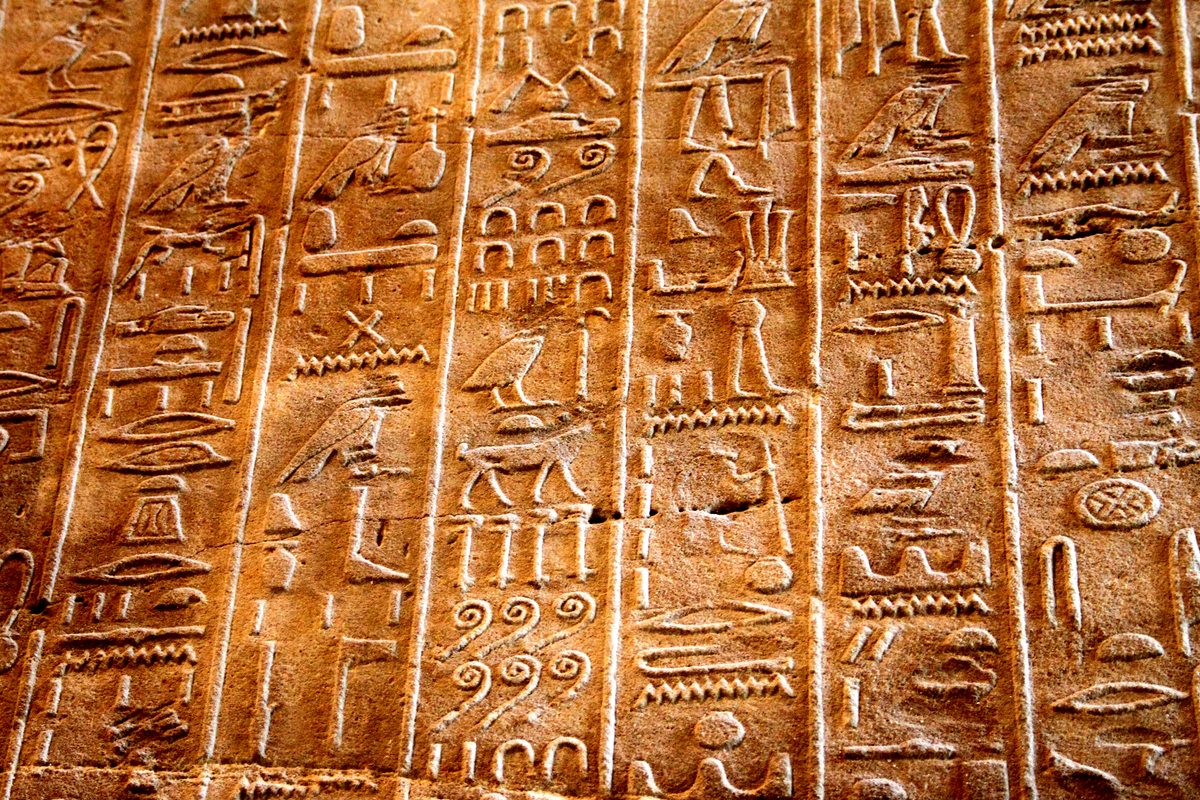

Who do you think of when you think of ancient civilizations? Romans? Greeks? Chinese? India? Egyptians? What about the Scythians, the Muisca, Gana, or the Kerma? You might not recognize that second group as readily because they all didn’t have writing systems. The same goes, to a lesser extent, for the Etruscans, the Minoans, or the inhabitants of Easter Island where they wrote, but no one remembers how to read their writing. Even the Egyptians were mysterious until the discovery of the Rosetta stone. We imagine that an author writing in Etruscan didn’t think that no one would be able to read the writing in the future–they probably thought they were recording their thoughts for all eternity. Hubris? Maybe, but what about our documents that are increasingly stored as bits somewhere?

It was bad enough when you had punched cards and magnetic media. We are sure there are some tape formats that are no longer practical to read. Could you read a magnetic bubble cartridge? Would it even be viable after all these years? But the problem is even worse now. Where are your back copies of Hackaday? Where are your e-mails? “In the cloud” is a cliche, but appropriate. In 1,000 years there won’t be a Google server and whatever storage medium it is using today will likely be dust even if the people wanting to read it knew how.

And it gets worse. If you see a stone or a parchment with scribbles on it, you can deduce it is writing. What if you saw some strings with knots in them? The Incas used a system like that to record things. We still don’t know exactly how to read them. What will a future archeologist make of a flash card or a hard disk? They are as unlikely to use anything like it as we are to use a strigil — the Roman knife used to clean yourself. If you saw one of these with no context, you might assume it was a tool for carpentry, not a bathroom implement. Why would our future archeologists think that some little boxes might have writing inside of them if you knew how to read them?

Antique Media vs Modern Media

At least some of the oldest media have some chance of surviving. Punched cards and paper tape are probably about as robust as books. Like a stone tablet, too, it should be pretty obvious that they hold data and they are easy to decode, even by hand.

Magnetic things are less certain, though. Tape-based oxides aren’t going to last forever and the magnetic information on them is even more fragile. Optical media might last, but it is far from certain you’d realize there was data encoded. They might be mistaken for art. Tape has the same problem. It would be easy to imagine some future museum showing tape used for some unknown religious ritual involving sanctuaries with raised floors.

Modern media is likely to be flash based and that certainly won’t last forever. It is even harder to realize there might be something on them. Even now, I can see a half a dozen USB devices on my desk, half of which are not flash drives but don’t look very different.

Then there’s all the cloud data. Sure, it is really stored somewhere on a hard drive (magnetic media or flash). Presumably, if future archeologists found a buried data center, somewhere, they might unlock tons of data, but only if they realized what it was and how to read it.

Encoding Problems

Even today, it can be difficult to read a disk written on one system if you don’t have that system. It has gotten somewhat easier, in some common cases, because a few formats are near universal, but there are always outlier cases.

As a thought experiment, though, imagine you are a future archeologist studying 21st-century ruins. Your assistant brings you a little black rectangle the size of your thumbnail marked “32 GB, Class 10.” First, you need to realize it is a flash device. Then you’ll need to understand how to power it up and send it the right commands over the serial bus to pull the data off of it.

But the fun’s just starting. With the data, you’ll need to figure out the file system format. Then you get to dig into the different kinds of files, each of which will be a science project in of itself. PDF files? Images and video? Good luck. Imagine if the Egyptians used a different set of hieroglyphics for different purposes and then subjected them to data compression to minimize redundancy.

Real Life

We aren’t the only ones thinking about this. The University of Göttingen, for example, manages 5 petabytes of data in a “forever” archive collected over the last 40-some-odd years. They claim that the tapes they use have a 20-30 year lifespan, but the technology to manage them only lasts 10 years. So they are constantly moving data from one medium to the next, which takes about two years to complete. Of course, if they were to stop operating, you can assume in 300 or 400 years, there won’t be much chance of retrieving any of the data.

There is no shortage of services to store your data “forever” in the cloud, but it is hard to see how they can really assure that and what it would mean if it didn’t work. For example, Ardrive uses the “blockweave” to store data in a distributed way, but it is easy to imagine any number of ways this could be disrupted. As Adam Farquhar, head of digital preservation at the British Library has said, “If we’re not careful, we will know more about the beginning of the 20th century than the beginning of the 21st.”

Not that paper records are much better. Paper deteriorates. Languages are lost. The library at Alexandria famously burned. But stone seems to last. Ironically, we know a lot about Akhenaten — King Tut’s father — because the Egyptians tried to erase him from history by destroying his work. They reused the stones, often as a foundation for new construction and so we have found much of it well-preserved.

As we push to more exotic storage media, the problem just gets worse. We’ve read about storing data in glass (see the video below) and molecular storage at 80K using liquid nitrogen. None of this is going to be more obvious or more survivable than what we are using today. In fact, a lot of it will make the problem worse.

We can’t tell how serious they are, but the “Billion Year Archive” project did send a quartz disk with Isaac Asimov’s Foundation trilogy in the glove box of Elon Musk’s space-traveling Tesla. They also apparently sent a library to the moon in 2019. However, these libraries use DNA storage which seems odd since we have trouble recovering old DNA today and also by etching tiny text into thin nickel films. Besides that, the probe it was hitching a ride with crashed, and the survival of the library is in question.

It is difficult, however, to visualize our post-apocalyptic archeologist wandering the moon and realizing the significance of some metal foil and a few crystals. That leads us to two interesting questions: First, how could you store obvious data for the distant future in such a way that it survives and is understandable? The question is sort of like the alien messages where it is difficult to figure out what another being could decode. Without that answer, we could become another mysterious “lost civilization” one day.

The second question is: what if this has happened before? It smacks of crackpot science, but what if some ancient artifact has information encoded on it and we don’t even recognize it? Of course, some of them we recognize, but we don’t know what to do about them like the Incan knots in the video below. Got an answer to either of these questions? Leave them in the comments.

[Banner image: “Egyptian Hieroglyphics” by Martie Swart