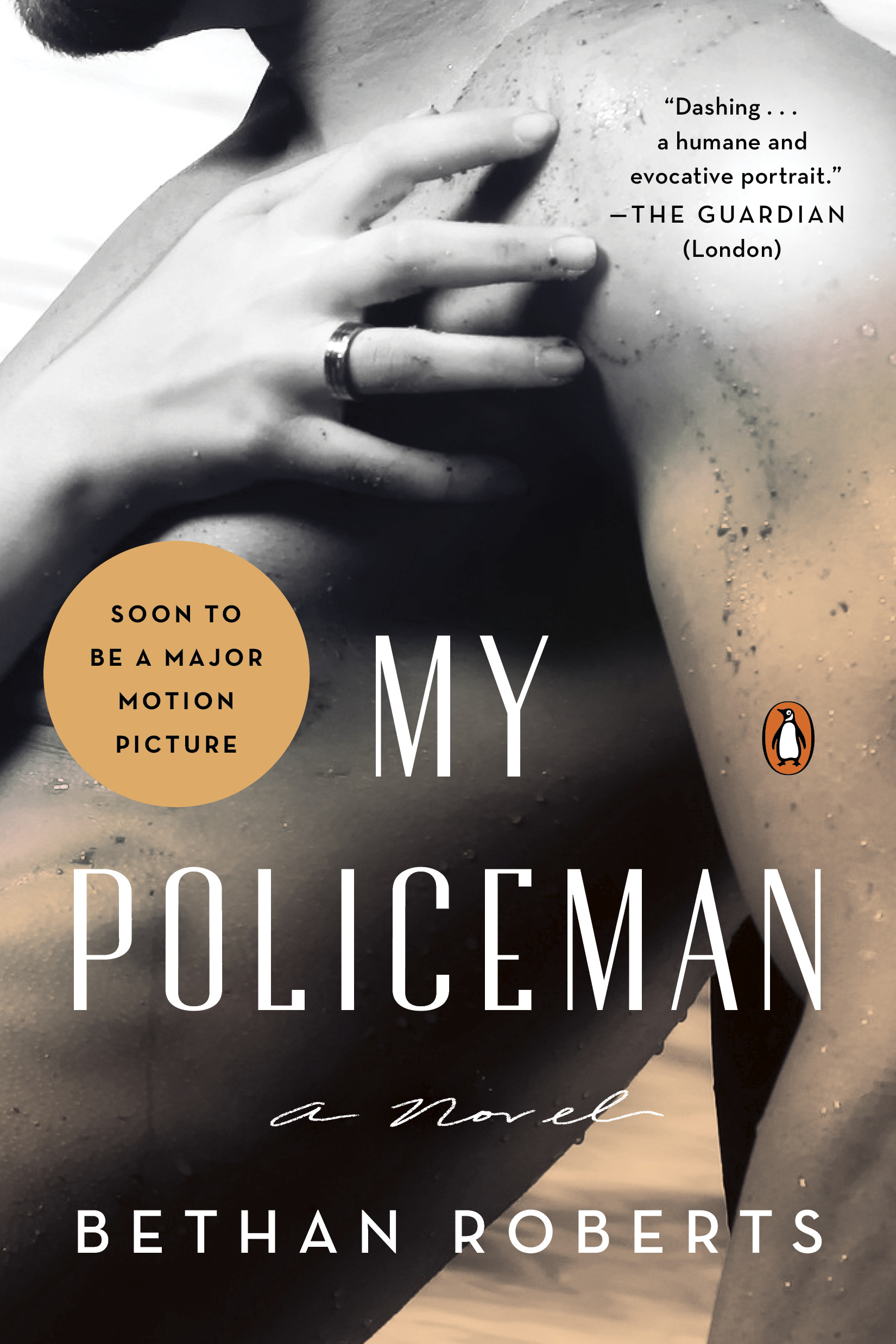

My Policeman

Posted by admin on

I considered starting with these words: I no longer want to kill you—because I really don’t—but then decided you would think this far too melodramatic. You’ve always hated melodrama, and I don’t want to upset you now, not in the state you’re in, not at what may be the end of your life.

What I mean to do is this: write it all down, so I can get it right. This is a confession of sorts, and it’s worth getting the details correct. When I am finished, I plan to read this account to you, Patrick, because you can’t answer back anymore. And I have been instructed to keep talking to you. Talking, the doctors say, is vital if you are to recover.

Your speech is almost destroyed, and even though you are here in my house, we communicate on paper. When I say on paper, I mean pointing at flashcards. You can’t articulate the words, but you can gesture toward your desires: drink, lavatory, sandwich. I know you want these things before your finger reaches the picture, but I let you point anyway, because it is better for you to be independent.

It’s odd, isn’t it, that I’m the one with pen and paper now, writing this—what shall we call it? It’s hardly a journal, not of the type you once kept. Whatever it is, I’m the one writing, while you lie in your bed, watching my every move.

You’ve never liked this stretch of coast, calling it suburbia-on-sea, the place the old go to gaze at sunsets and wait for death. Wasn’t this area—exposed, lonely, windswept, like all the best British seaside settlements—known as Siberia in that terrible winter of ’63? It’s not quite that bleak here now, although it’s still as uniform; there’s even some comfort, I find, in its predictability. Here in Peacehaven, the streets are the same, over and over: modest bungalow, functional garden, oblique sea view.

I was very resistant to Tom’s plans to move here. Why would I, a lifelong Brighton resident, want to live on one floor, even if our bungalow was called a Swiss chalet by the estate agent? Why would I settle for the narrow aisles of the local Co-op, the old-fat stench of Joe’s Pizza and Kebab House, the four funeral parlors, a pet shop called Animal Magic and a dry cleaner’s where the staff are, apparently, “London trained”? Why would I settle for such things after Brighton, where the cafés are always full, the shops sell more than you could possibly imagine, let alone need, and the pier is always bright, always open and often slightly menacing?

I’ve given this bedroom to you, and have arranged your bed so you may see the glimpse of the sea as much as you like. I’ve given all this to you, Patrick.No. I thought it an awful idea, just as you would have done. But Tom was determined to retire to a quieter, smaller, supposedly safer place. I think, in part, he’d had more than enough of being reminded of his old beats, his old busyness. One thing a bungalow in Peacehaven does not do is remind you of the world’s busyness. So here we are, where no one is out on the street before 9:30 in the morning or after 9:30 at night, save a handful of teenagers who smoke outside the pizza place. Here we are in a two-bedroom bungalow (it is not a Swiss chalet, it is not), within easy reach of the bus stop and the Co-op, with a long lawn to look out on and a whirligig washing line and three outdoor buildings (shed, garage, greenhouse). The saving grace is the sea view, which is indeed oblique—it’s visible from the side bedroom window. I’ve given this bedroom to you, and have arranged your bed so you may see the glimpse of the sea as much as you like. I’ve given all this to you, Patrick, despite the fact that Tom and I never before had our own view. From your Chichester Terrace apartment, complete with Regency finishings, you enjoyed the sea every day. I remember the view from your apartment very well, even though I rarely visited you: the Volk’s railway, the Duke’s Mound gardens, the breakwater with its crest of white on windy days, and of course the sea, always different, always the same. Up in our terraced house on Islingword Street, all Tom and I saw were our own reflections in the neighbors’ windows. But still. I wasn’t keen to leave that place.

So I suspect that when you arrived here from the hospital a week ago, when Tom lifted you from the car and into your chair, you saw exactly what I did: the brown regularity of the pebble dash, the impossibly smooth plastic of the double-glazed door, the neat conifer hedge around the place, and all of it would have struck terror into your heart, just as it had in mine. And the name of the place: The Pines. So inappropriate, so unimaginative. A cool sweat probably oozed from your neck and your shirt suddenly felt uncomfortable. Tom wheeled you along the front path. You would have noticed that each slab was a perfectly even piece of pinkish-gray concrete. As I put the key in the lock and said, “Welcome,” you wrung your wilted hands together and pulled your face into something like a smile.

Entering the beige-papered hallway, you would have smelled the bleach I’d used in preparation for your stay with us, and registered the scent of Walter, our collie-cross, lurking beneath it. You nodded slightly at the framed photograph of our wedding, Tom in that wonderful suit from Cobley’s—paid for by you—and me in that stiff veil. We sat in the living room, Tom and I on the new brown velvet suite, bought with money from Tom’s retirement package, and listened to the ticking music of the central heating. Walter panted at Tom’s feet. Then Tom said, “Marion will see you settled.” And I noticed the wince you gave at Tom’s determination to leave, the way you continued to stare at the net curtains as he strode toward the door saying, “Something I’ve got to see to.”

The dog followed him. You and I sat listening to Tom’s footsteps along the hallway, the rustle as he reached for his coat from the peg, the jangle as he checked in his pocket for his keys; we heard him gently command Walter to wait, and then there was only the sound of the suction of air as he pulled the double-glazed front door open and left the bungalow. When I finally looked at you, your hands, limp on your bony knees, were shaking. Did you think, then, that being in Tom’s home at last might not be all you’d hoped?

__________________________________

Excerpted from My Policeman by Bethan Roberts. Reprinted with permission of the publisher, Penguin Books. Copyright © 2012 by Bethan Roberts.