Meet the 2022 National Book Award Finalists

Posted by admin on

The winners of the 73rd National Book Awards—given every year in Young People’s Literature, Translation, Poetry, Nonfiction, and Fiction—will be announced next week in a ceremony hosted by Padma Lakshmi at Cipriani Wall Street in New York City (and streamable online). Ahead of the festivities, Literary Hub caught up with (almost) all the finalists to ask them a bit about their books, their reading habits, and their writing lives.

*

FICTION

Tess Gunty, author of The Rabbit Hutch

What time of day do you write?

I read and revise during the day, but I write best at night, often until four or five in the morning. I know that no one will contact me during that window, so the distraction of digital communication is eliminated. Dusk to dawn feels secret and stolen, a hinterland of a workday when the subconscious is accustomed to monarchic reign, so it’s easier to trust associative logic. I am nocturnal by nature, and nightfall releases herds of feral energy through my brain. I need to steer them into work, otherwise they’ll attack me.

How do you tackle writer’s block?

Usually by reading poetry or language-driven prose. Art museums, music performances, films, swimming, theater, hiking, comedy, volunteering, cooking, learning, French, mysteries, painting, traveling, house projects, research rabbit holes, friends, family, and non-human animals also help. In short: living.

What’s the best writing advice you’ve ever received?

Here’s a sampling, mostly paraphrased. I’m not sure that all of it qualifies as advice, but these are the soundbites that guide me, especially during revision. Yusef Komunyakaa: This line is already there. Lydia Davis: Always keep at least one project to yourself until it’s drafted. Jeffrey Eugenides: “Pretend it’s the best letter you ever wrote to your smartest friend.” Joyelle McSweeney: I am drawn to indivisible opposites—things that are double but not binary. Joan Didion: Keep a notebook. Anne Carson: “Edit ferociously and with joy; it is very fun to delete stuff.” Zadie Smith: Put your manuscript in a drawer until you become its reader rather than its writer. Jonathan Safran Foer: It is better to write a book that nobody but you loves than it is to write a book that everybody but you loves. Kurt Vonnegut: “Write to please just one person. If you open a window and make love to the world, so to speak, your story will get pneumonia.” Rivka Galchen: What is the engine? Rick Moody: This seems like shorthand for something more interesting.

Which book(s) do you reread?

The work of Anne Carson bounteously rewards rereading. I especially love The Beauty of the Husband, Autobiography of Red, Red Doc, and Glass, Irony and God. Most of the Anne Carson books that I own are cockled and warped by lakes, bath water, pool water, oceans, and seas.

What is your favorite way to procrastinate when you are meant to be writing?

I like cooking complicated meals in the middle of the day while listening to an audiobook, podcast, lecture—often related to science or history. I feel almost manically ravenous for knowledge. Usually, the meal involves peeling and chopping an unreasonable variety of vegetables. Then, after I eat, I go for a long walk. Not only does this practice free my evenings—I can eat something light and easy for dinner and can therefore dive into a long writing session around dusk—but it also creates psychological weather that nourishes ideas. The interaction between tactile, physical labor and intellectual, imaginative labor is generative. I won’t always have wide-open pastures of time in my days, and I intend to wander every inch of them while I can.

Jamil Jan Kochai, author of The Haunting of Hajji Hotak and Other Stories

The Haunting of Hajji Hotak and Other Stories; cover design by Zak Tebbal (Viking, July 19)" data-image-description data-image-caption data-medium-file="https://s26162.pcdn.co/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/hotak-199x300.jpg" data-large-file="https://s26162.pcdn.co/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/hotak-678x1024.jpg" loading="lazy" alt="Jamil Jan Kochai, The Haunting of Hajji Hotak and Other Stories; cover design by Zak Tebbal (Viking, July 19)" data-orig-srcset="https://s26162.pcdn.co/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/hotak-199x300.jpg 199w, https://s26162.pcdn.co/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/hotak-678x1024.jpg 678w, https://s26162.pcdn.co/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/hotak-768x1160.jpg 768w, https://s26162.pcdn.co/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/hotak-40x60.jpg 40w, https://s26162.pcdn.co/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/hotak-33x50.jpg 33w, https://s26162.pcdn.co/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/hotak.jpg 1000w" src="https://s26162.pcdn.co/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/hotak.jpg">

How do you tackle writer’s block?

I read. I surround my writing desk with books, so whenever I run into a problem with one of my stories, I’ll either start reading something beautiful at random, or else, I’ll search for a specific section of a book (One Hundred Years of Solitude is a novel I return to frequently) to give me an idea of how I can write myself out of my problem.

What’s the best or worst writing advice you’ve ever received?

“Show don’t tell” is not necessarily bad advice, and, in fact, it’s something I’ve told my students on occasion, but “show don’t tell” was definitely writing advice that initially hampered my stories a great deal because it restricted me to writing almost exclusively in scene. Thus, it took me some time to understand the magic of “telling.”

Which non-literary piece of culture—film, tv show, painting, song—could you not imagine your life without?

I find myself frequently returning to the films of Hayao Miyazaki. Not only are they beautifully drawn and designed and narrated, but there is something particularly therapeutic about Miyazaki’s movies (in particular Princess Mononoke and Kiki’s Delivery Service) which I have not found in any other form of art. There is something about the tone and pace of his films that captivate but also calm me. I feel a soft, quiet joy while watching his tales unravel upon the screen. I couldn’t imagine life without them.

What book has elicited the most intense emotional reaction from you?

I laughed out loud multiple times while reading The Idiot by Fyodor Dostoyevsky. That book was surprisingly hilarious. The last two scenes in “Sonny’s Blues” always makes me cry. I teach that story almost every year and it never fails to move me. This Blinding Absence of Light is the book that had the most visceral impact upon my body. Certain passages would make my heart drop and I could hardly breathe. Finally, Look by Solmaz Sharif probably gave me the most goosebumps.

If you weren’t a writer, what would you do instead?

Law. For years, I promised my father I was going to use my English degree to apply for law school. I was enrolled at a pre-law bootcamp at UC Davis and everything. Instead, I managed to luck my way into a career in creative writing.

Sarah Thankam Mathews, author of All This Could Be Different

Who do you most wish would read your book? (your boss, your childhood bully, etc.)

My landlords past and present. Would probably open up a right can of worms, though.

What time of day do you write?

Whenever I can make it happen; that’s the most truthful answer. But my best writing is often done late at night, when everyone’s asleep and my mind feels like it belongs only to itself.

How do you tackle writer’s block?

I pay attention to it. I try to see what it is telling me about the work or myself.

What part of your writing routine do you think would surprise your readers?

Usually, I write using photograph stand-ins for most major characters, and sometimes minor characters. Often, I’ll listen to ambient music, like thunderstorms or drone noise, for hours. My Spotify Wrapped looks so crazy.

Which non-literary piece of culture—film, tv show, painting, song—could you not imagine your life without?

In terms of immense impact at a formative time, issa three-way tie between Sleep (1932) by Amrita Sher-Gil, Billy Elliot (2000) by Stephen Daldry, and Channel Orange (2012) by Frank Ocean.

If you weren’t a writer, what would you do instead?

There have been different answers to this at different points in my life. Maybe: high school teacher, urban farmer, or co-founder of an Indian furniture and textile emporium with a really dank attached café.

Alejandro Varela, author of The Town of Babylon

Who do you most wish would read your book? (your boss, your childhood bully, etc.)

• Ken Loach because I want him to adapt it into a film.

• Pedro Almodóvar because I want him to adapt it into a film.

• Ramy Youseff because I want him to adapt it into a TV series.

• Jamaica Kincaid because, of course.

What time of day do you write ?

Whenever I’m alone, preferably in the morning. I can edit in spurts. If I have 20 minutes, I’ll make do. But the writing of something new, the first draft, requires a chunk of time (hours) by myself.

How do you tackle writer’s block?

I read other people’s work.

What’s the best or worst writing advice you’ve ever received?

Best: Don’t look back while you’re writing something longform. Don’t stop to re-read or edit.

Who is the person, or what is the place or practice that had the most significant impact on your writing education?

A teacher’s assistant in one of my college classes was mean and maybe a little racist, but she’d meet me in the local bar and give me writing feedback. I’m not suggesting cruelty is an appropriate or advisable teaching tool, but I was, then, impressionable, focused on succeeding, and oblivious to the rest. At another point in my life, her words might have knocked me down. In a nutshell, she told me my writing sucked and I didn’t know what I was doing—she also kept asking me if I was “from this country.”

I was, to put it mildly, shocked, but her assessment forced me to see my work differently, to revisit my approach. I continue to appreciate direct criticism—nothing sugarcoated please—but preferably not racist. Another teacher in college, also a PhD student, would pull me aside after class and tell me I had great potential. She’d encourage me to apply for grants and programs that I never applied to because I was too busy drinking away my insecurities. And there was a teacher (in graduate school) who told me to stop using passive voice, but she was very kind about it.

What part of your writing routine do you think would surprise your readers?

I don’t sketch or outline anything. I develop an idea in my mind until I can no longer retain more information. Only when it seems as if I’m beginning to forget details of the story do I sit down at my laptop and begin writing.

Which non-literary piece of culture—film, tv show, painting, song—could you not imagine your life without?

All of the above, but film primarily. The narrative power of film has marked my life. I am who I am because of film (and TV)—and because I grew up in a state of financial precarity.

What was the first book you fell in love with?

The Count of Monte Cristo first held my attention. Something about being an outsider bound me to the protagonist. His adversarial life resonated with my own. Giovanni’s Room felt more like a breakup than a courtship, but incredibly meaningful nonetheless. The Farewell Symphony made me weep, in a way that could have been mistaken for love. The Bluest Eye, however, was the first where I thought, Oh, this is the complete package.

Which book(s) do you reread?

I don’t re-read. I will skim or pick up for inspiration. See: The Bluest Eye response above.

What is your favorite way to procrastinate when you are meant to be writing?

I watch award show acceptance speeches on YouTube. Recommend: Martin Short’s Tony speech at the Emmys; Alfre Woodard at the Golden Globes; Elaine Stritch at the Emmys; Luther Vandross at the Grammys; and Roberto Benigni at the Oscars.

What book has elicited the most intense emotional reaction from you?

See response [above]. I’d also add An Indigenous Peoples’ History of the United States by Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz and The Massacre at El Mozote by Mark Danner, both of which recount the history of U.S.-led and -funded genocide in the Americas. Infuriating, horrifying, radicalizing work.

How do you decide what to read next?

I try to alternate between canonical writing that I’ve not yet read and contemporary writing to keep me on my toes.

What’s one book you wish you had read when you were young?

I didn’t have the requisite attention span in my youth. I’ve grown into the reader I am today. I fear I wouldn’t have appreciated my current favorites back then.

What do you always want to talk about in interviews but never get to?

• Reparations for slavery

• the hypocrisy and disingenuousness of US politicians who talk about universal health care as radical and dangerous but who then treat the UK as our greatest ally despite its National Health Service—all their health care workers are government employees

• polyamory

• the importance of gender self-determination

• Palestine

• the water crises in Flint, Michigan and Jackson, Mississippi

• Puerto Rican independence

• the Song of the Year category at the Grammys

If you weren’t a writer, what would you do instead?

I’d write public health policy briefs for grassroots organizations fighting for collective liberation.

Gayl Jones, author of The Birdcatcher

Read an excerpt from The Birdcatcher · Read Helene Atwan on working with Gayl Jones.

•

NONFICTION

Meghan O’Rourke, author of The Invisible Kingdom: Reimagining Chronic Illness

Who do you most wish would read your book? (your boss, your childhood bully, etc.)

Great question! Probably doctors who gaslight their patients or treat patients without much awareness of the complex chronic illnesses I write about (including some of those physicians I saw along the way). But the book is for everyone: People living with pain and illness, their friends, clinicians. I keep hearing from people who don’t live with chronic illness that they are glad they read the book, because it felt like a detective story (which I guess means it wasn’t onerous to read!) but also left them with a new understanding of the medical system and the bodies we all live in.

What time of day do you write?

I used to write at late night, but now I mostly write in the very early morning. It is when I have the most focus—and my children aren’t up, telling me jokes, needing milk, and very few people are emailing or needing things. These days, to tell the truth, I have to write whenever the chance presents itself, but I most love writing in the “secret” times when the world is quiet and my mind can rove.

What’s the best or worst writing advice you’ve ever received?

Best advice: Just try to be in your chair at your desk every day. Even for 15 minutes.

Worst advice: If you’re not writing every day, you’re not a serious writer. As The Invisible Kingdom describes, I was sick for a long period of time and couldn’t write regularly. I often work with writing students with chronic illness whose health is unpredictable and who can’t write every day, and they feel confused by (and excluded from) this advice. I think writing is something you have to commit to, but in a way that makes sense for you. The idea that we can all sit down and produce, day after day, is very much shaped by forces (of late capitalism, of ableism, of incuriosity about invisible illness) that I try to interrogate in my book.

So I’m here to say: It’s OK to be a writer who doesn’t write every day! But try to be noticing/reading/thinking even when you can’t be at your desk. When I was really sick, I took notes on my iPhone notes app when I could—just a sentence, sometimes. And some of that made it into my book.

Who is the person, or what is the place or practice that had the most significant impact on your writing education?

Ruth Chapman at Saint Ann’s School, where my parents were teachers, and where I went to school. Her classes lit my imagination on fire and so did her writing assignments. But it was all the teachers at Saint Ann’s who taught me writing: Jim Halverson, Nancy White, who made me feel I could be a writer, Beth Bosworth, whose steady commitment to writing—it was these teachers who made me love writing and showed that a writing life was something people really had. So often, the match that lights the flame is a middle school or high school writing teacher.

What part of your writing routine do you think would surprise your readers?

I wrote a lot of The Invisible Kingdom while listening to the Brian Lehrer show on WNYC. For a period working on it, I liked to time sitting down to write at my desk with the opening jingle of his show. It’s bouncy—my son as a baby used to bob his head to it—and energizing. And it trained my brain that now it was time to focus and write, like Pavlov’s dogs learning that the bell meant it was time to eat. I still like to “start” a difficult chunk while listening to the radio. I think it’s because I was a gymnast as a kid and gymnasts always perform with lots of noise around; deep concentration still comes easiest with a certain kind of ambient noise around me.

What is your favorite way to procrastinate when you are meant to be writing?

I like to walk about and organize things in the house randomly. It’s an optimal form of procrastination, because you leave things in better shape than they were, you’re on your feet, getting blood moving; and it is boring and meditative, so I find I start writing sentences in my head.

And when that flow has built up enough, I go sit at my desk. If not that, a walk: you can start a walk feeling creatively dry as the desert, but you always end it with sentences and ideas taking shape. I wrote the ending of my memoir The Long Goodbye and the ending of The Invisible Kingdom in my head on long walks (pausing to take notes). Never exercise without a phone or tiny pocket notebook. (As you can tell, some of these walks turn out not to be very good workouts.)

Imani Perry, author of South to America: A Journey Below the Mason-Dixon to Understand the Soul of a Nation

Who do you most wish would read your book? (your boss, your childhood bully, etc.)

The people who I most wish for as readers are no longer living, like my dad. He used to read every word I wrote.

What time of day do you write?

I’ve been a mother for 19 years and that has meant that I write whenever I have a snatch of time, and I choose to feel accomplished even if I’ve only written a single sentence. But my favorite time to write is between 4 and 6am.

What’s the best or worst writing advice you’ve ever received?

Mr. McFarland my high school Writing Seminar teacher taught us how to use the rhythm and length of sentences deliberately.

Who is the person, or what is the place or practice that had the most significant impact on your writing education?

The South, specifically my birthplace, Birmingham Alabama. Language is so artful there. Even the silences speak volumes. My favorite part is the nonverbal communication like the polyrhythmic “mmm” sounds in a conversation. I try to channel that kind of everyday art in my writing.

What part of your writing routine do you think would surprise your readers?

I spend months and sometimes years outlining. Form is hugely important to me, but I want to ultimately achieve natural form, like the geometry of a leaf. I don’t want the beams and seams to show. So, I don’t think it’s necessarily apparent to readers how much architecture there is in my writing. At least, I hope not. But it’s there.

Which non-literary piece of culture—film, tv show, painting, song—could you not imagine your life without?

The Commodores song “Zoom.” It’s a perfect song to me.

What was the first book you fell in love with?

Ezra Jack Keats’ The Snowy Day. Here’s this little Black child in a red snowsuit named Peter, who makes his mark on the world by happily tracking his way through the snow. It’s simple but also profound. I have such a strong visceral memory of that book that I can recall how it felt in my hands when I was 5 years old. And the colors are muted yet gorgeous and rich. Reading it was an ideal experience.

Which book(s) do you reread?

I reread a lot, but Moby-Dick and Song of Solomon most frequently.

What book has elicited the most intense emotional reaction from you?

Reading is generally a deeply emotional event for me, but in the last couple of years Douglass Stuart’s Shuggie Bain stands out for me for how he captured the grief of living. I cried and laughed all the way through that book and I simply adore the protagonist, Shuggie.

How do you decide what to read next?

If I hear exceptional praise of a writer who I’ve never heard of, I try to start a book by that person as soon as possible. Especially if they’re from somewhere I’ve never been.

What’s one book you wish you had read when you were young?

I wish I had read Saramago’s Blindness when I was in my 20s instead of in my 40s. I re-read it with my brilliant 15 year old cousin Gianna last year and I loved witnessing how it affected her. Learning what Saramago teaches us about the human condition as a young adult, especially about fear and making do, would have been so useful for me.

What do you always want to talk about in interviews but never get to?

Craft. I like talking about the subject matter of my writing of course, but there’s so much content in composition as well. I’m a hopeful romantic and a lot of the romantic part of writing is in craft.

If you weren’t a writer, what would you do instead?

Well, I would still be a professor. But I would also love to be a textile designer. And if I could sing well, I would be a vocalist and I would be insufferable. I’d be singing every sentence.

David Quammen, author of Breathless: The Scientific Race to Defeat a Deadly Virus

How do you tackle writer’s block?

Writer’s block is an interesting, delicate subject. In 52 years as a professional writer, I’ve never experienced it. I tend toward thinking that “blocked” is the wrong metaphorical adjective for when writers can’t write. I think “empty” might be better. But I’m not complacent or unsympathetic about this; my view could change based on experience, or I might find myself empty at some point. I think of writer’s block in the same terms as insomnia. I sleep well . . . but knock wood. It could get me too.

What’s the best or worst writing advice you’ve ever received?

Worst advice: Always make an outline. Bunk. Careful, detailed outlines—it seems to me—yield boring, schematic books.

Who is the person, or what is the place or practice that had the most significant impact on your writing education?

Robert Penn Warren was my teacher, my mentor, and my friend. I never took a writing course from him, and he never told me how to write. But he was immeasurably supportive of me, and he showed me by example one very important truth: A writer is not required to be only one kind of writer. Warren wrote novels, poetry, literary criticism, cultural history, biography. He was a man of letters.

Which book(s) do you reread?

I believe strongly in the value of rereading great books. It’s one of the fundamental ways of teaching yourself to write. The first time through, you see what the author did; second time through, you start to see how he or she did it. I’ve reread all of Faulkner’s major novels, at least one of them (Absalom, Absalom!) roughly eleven times. I also reread Joan Didion, Raymond Chandler, John Le Carré, and The Sun Also Rises, among others. In nonfiction, Barbara Tuchman merits rereading because the history is so rich and dense, and her prose is so wry and deft. David Fromkin’s A Peace to End All Peace I will also keep rereading, again because there’s so much to absorb and remember. Of course Anna Karenina. In the past several years, for obvious reasons, I reread Camus’s The Plague. It was very analgesic. And I’ve reread On the Origin of Species a few times and probably will again: a book so straightforward yet profound and epochal, and still right about so many things, that it deserves to be read carefully and repeatedly. It strikes me as crazy that a young person can get a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology, true fact, without ever having read Darwin’s great book. People think they know what’s in it from cultural osmosis. They don’t.

If you weren’t a writer, what would you do instead?

Among the roads not taken, for me, were to be an entomologist or, like my friend Harry Greene, a herpetologist. I’m probably not smart enough to be a molecular evolutionary biologist, alas, and that option never occurred to me when I was young (molecular biology was young too), but I suspect that would be vastly satisfying too. On another note, my role model when I was 17 was Tommy Smothers. Comedy and music. But among other barriers along that route was the fact that, by empirical evidence, it was established that I had no talent whatsoever for music.

Ingrid Rojas Contreras, author of The Man Who Could Move Clouds: A Memoir

What time of day do you write?

I mostly write in the morning, just after getting up. I love the quality of my thinking then, how it’s so close to whatever happens when I dream. I always try to take advantage of that time. The other time I love to write is late at night, either before or after dinner. Words come differently then too. Any other time of day, I feel too awake, and the writing I do tends to come out too calculated.

How do you tackle writer’s block?

If I get stuck in a particular piece, I track back until I come to the last place where things in the writing were really singing. I then see if there are different decisions I can take. I try to branch out the story in a new way. If this still leaves me stuck, I go outside. I see friends, catch a movie, go rollerskating, look at some art, spend time in nature, go swim. Sometimes there’s something that I need to think about, and it needs to happen off the page, and the best way for me to do that is by doing something else entirely.

Who is the person, or what is the place or practice that had the most significant impact on your writing education?

I always say that my first writing school was listening to my mother tell stories out loud. We did that a lot as a family. Colombia is also a place where oral stories are often told in plazas and street corners. There is a rich tradition there. My mother is the best storyteller I know. And, as I started to take writing seriously, the richest engagement I have found with craft, has been thinking about how my mother tells story. I love to notice the shape of her stories, and her language. She has incredibly precise, hilarious language.

Which book(s) do you reread?

I love to reread Ocean Vuong’s On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous, Louise Erdrich’s Love Medicine, Gabriel García Marquez’s One Hundred Years of Solitude, and all books by Solmaz Sharif, Natalie Diaz, and Kaveh Akbar. Teaching is so wonderful, because you really get to re-read a lot of books, and think about them deeply alongside others. For my classes, I favor a lot of Toni Morrison. Her work is so powerful, and a joy to re-read.

What is your favorite way to procrastinate when you are meant to be writing?

I have a rock microscope and sometimes will just start to look at random things on it. Sometimes rocks, other times things I have around my house that I am curious about. I have spent a long time studying my own hand and nails up close. We don’t often get to see the blown-up texture of things, and I find it deeply fascinating. My favorite rocks to look at are translucent crystals, because under a microscope, with both your eyes fitted into the eyepiece, it starts to feel like you’re floating above a moonscape.

Robert Samuels and Toluse Olorunnipa, authors of His Name Is George Floyd: One Man’s Life and the Struggle for Racial Justice

Toluse Olorunnipa

How do you tackle writer’s block?

I’m a fan of a good nap to reset and refresh the brain. For me, writer’s block is a sign that something is off in the delicate balance required to write, and I rarely get much out of trying to force it or power through the mind fog (much respect to those who have the willpower to do that). Of course, deadlines are real and when they’re fast-approaching, there’s often no choice but to try to keep writing. If I can’t lay my head down and close my eyes for a few minutes, I try to take a walk, or listen to a song, or flip to a random page of another book and read a little to see if something might click. When all else fails, I’ll steal a line from Yoko Ogawa, author of The Memory Police, who answered this same prompt with these incisive words: “By just writing. Even when I can’t write, I write.”

Who is the person, or what is the place or practice that had the most significant impact on your writing education?

My parents—whose own improbable journey from small villages in Nigeria to America was paved by education—instilled in me a reverence for books from an early age. They would encourage me to approach every task with the exquisite eye for detail of a writer. “Do it in a way that you would be proud to put your signature on it,” my mother would say, after instructing me to re-clean the bathtub. If there be any precision or meticulousness in my writing, I owe it to my parents who never stopped making me believe I could be excellent.

The “place” would be the Leon County Public Library in Tallahassee, Florida, where my father deposited me and my siblings for hours on end during the summers while he was working. With nothing else to do but read, I lost myself in worlds fashioned by imaginative authors, and developed a love for literature and libraries that endures to this day.

Which non-literary piece of culture—film, tv show, painting, song—could you not imagine your life without?

Nollywood movies, Afrobeats, and Nigerian food. The artistry from the land of my ancestors is bursting at the seams with beauty, drama and joy.

It’s almost cheating to describe any of this as non-literary, as Nigerian culture is so steeped in storytelling and language—but it gives me so much joy to see the world come to appreciate the intricate magnificence of those stories.

What is your favorite way to procrastinate when you are meant to be writing?

Watching YouTube videos of battle rap. As a writer, I marvel at the lyrical agility of people who can do such mind-boggling things with nothing but their minds and the 26 letters of the English language. The puns, polysyllabic rhyme schemes, double- and triple-entendres, metaphors, alliteration and humor all mixed with unhealthy levels of aggression serve to make the entire enterprise magically ridiculous.

What book has elicited the most intense emotional reaction from you (made you laugh, cry, be angry)?

The Holy Bible.

*

Robert Samuels

Who do you most wish would read your book? (your boss, your childhood bully, etc.)

My friends’ children, in fourteen or fifteen years. So many of them were between the ages of two and four years old when George Floyd died. In so many ways, I wrote the text for them, hoping they would be able to pick up His Name is George Floyd to understand this incredible moment that happened when they were just getting started. I imagined them picking it up in a bookstore or in a classroom, marveling at what has changed in the world , maybe getting a little upset at the things that have not changed, and gaining a deeper of understanding of the reasons why things are the way they are.

How do you tackle writer’s block?

I try to find inspiration in things that have nothing to do with traditional writing. I’ll watch old figure skating clips (Michelle Kwan’s 2000 and 2001 world championship long programs are two faves) of times when a competitor digs into themselves and finds something amazing. I’ll hype myself up by watching 1980s professional wrestling promos from Macho Man Randy Savage.

If that does not work, I’ll watch one of my favorite movies (My Fair Lady and 1917) or listen to my favorite verses in Hamilton (the last verses of “My Shot” and “The Battle of Yorktown”) and remind myself that such brilliance came from human minds and hands, which encourages me to go back to the keyboard and try again.

What part of your writing routine do you think would surprise your readers?

I always heard writers talk about the importance of reading stories out loud. That never worked for me until I learned I needed to read my stories out loud to a someone else. It is best when the person is a little sleepy. That means, I often read passages to my partner late at night. I read them with voices and emotion, like I’m reading a bedtime story to a child. If my partner isn’t captivated, I take it personally and blame the writing—not the sleepiness. It’s my signal to rewrite the passage to make it more interesting.

Which non-literary piece of culture—film, tv show, painting, song—could you not imagine your life without?

This is totally not the typical choice for a person writing about race and racism, but Jimmy Eat World’s 2007 Chase this Light has been my life soundtrack for the past 15 years. Judge me if you must.

If you weren’t a writer, what would you do instead?

I’m not sure I’m equipped to do anything else! When I was growing up, I really wanted to be an animation storyboard artist, which I guess is still writing. I still have a fascination with archaeology and anthropology; the hunt for artifacts and making sense of relics of the past seems very similar to what we do as journalists.

•

POETRY

Allison Adelle Hedge Coke, Look at This Blue

How do you tackle writer’s block?

Have multiple projects going so that when procrastination hits (or you’re more in the music in your head than words in the fingers for any particular work) you can leap off and dive into an unaffiliated work-in-progress to distract yourself from your offness.

What’s the best or worst writing advice you’ve ever received?

“You are too young for a first book.” “You are too old for any emerging writer’s award.” (Said to me the same year in grad school, in my thirties.) Truth is, you are never too young or too old for anything in writing. The result might be different than at another time, but it doesn’t negate its potential.

What part of your writing routine do you think would surprise your readers?

That the routine changes shortly after it establishes. Improvisational, freewheeling, freestyle routines suit me. Will return to some that worked well, but not all.

What was the first book you fell in love with (why)?

Beautiful Joe, at four. A harrowing and complicated tale. It was my first novel. (Who doesn’t love their first novel?) My sister claims she listened to me cry myself to sleep each night while reading it. (This part is not in my memory.)

Which book(s) do you reread?

Sula, One Hundred Years of Solitude, Flight to Canada, Neon Vernacular, Dien Cai Dau, Avalanche, Hurdy-Gurdy, The Redshifting Web, Neruda & Vallejo: Selected Poems, Native Guard as an example of the too many books to mention. Read everything at least twice! The next often reveals more.

What is your favorite way to procrastinate when you are meant to be writing?

Watching films. The greatest escape since silent pictures. Ease in and soon you’ve forgotten all else.

Sharon Olds, Balladz

Who do you most wish would read your book? (your boss, your childhood bully, etc.)

The image this question brought up in me was the experience (which I’ve never had, or expected!) of getting on the subway and seeing someone sitting reading a book of mine!

Who is the person, or what is the place or practice that had the most significant impact on your writing education?

Galway Kinnell and I used to share new-written poems a lot, and out of that experience came the experience of workshops in which everyone, every morning, brought in a brand new first draft, and we talked about them—without criticism. Praise only (truth only)!

Which non-literary piece of culture—film, tv show, painting, song—could you not imagine your life without?

Watching basketball on TV, and reading detective and mystery fiction.

Which book(s) do you reread?

Moby-Dick. Also favorite mysteries, if enough time has passed since I last read them.

What is your favorite way to procrastinate when you are meant to be writing?

I love talking about (sometimes dancing about!) rhythm, meter, structure. Counterpoint between visual lines and heard lines. Something I think of as cut-and-thrust dirty dancing moves. The body of a poem, the spirit of a poem.

Roger Reeves, Best Barbarian

Who is the person, or what is the place or practice that had the most significant impact on your writing education?

There have been several people that have had a significant impact on my writing education and practice. First, Bill Connolly—the advisor to my high school newspaper. Then, Daniel Black—my college writing mentor who worked with me and believed in me when I was at the lowest points of my life. Lastly, James Magnuson—the head of the James A. Michener Center for Writers. Magnuson told me to treat writing like a 9 to 5, to show up every day for it whether I felt like it or not. From then on, I did.

Which non-literary piece of culture—film, tv show, painting, song—could you not imagine your life without?

Jazz. From big-band to bebop to spiritual jazz to the avant-garde. I learn so much about composition from jazz musicians.

What was the first book you fell in love with?

The first book I fell in love with was Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man. I was seventeen years old, had just finished my junior year of high school, and, in preparation for AP English, was given five books to read for the summer; Invisible Man was one of them. Walking home on the last day of school, I opened up the book and began reading it. I had never done this before—tried to read while walking and have only done it once since.

The book captivated me—its size, its plot, its language. I felt as if I were given a secret or a piece of incendiary literature. The book was a sort of contraband, and I wondered if the drivers in each passing car might be looking at me suspiciously. I felt such a thrill reading the book and for years after, I returned to the book and read it at least once every year. It was the first thing that I read to my daughter when she was born and in the neonatal intensive care unit with tubes and cords running in and out of her. Invisible Man is a book I constantly turn to as I work on my novel. That and Morrison’s Beloved of course.

How do you decide what to read next?

Often, I’m reading several things at once. Books that help me write poems. Books that help me write essays. Books that help me write fiction. Then, I’m reading books about jazz, which is one of my favorite areas to read about that is and is not connected to writing. Then, I’m reading books about economies, class, and history. Then, I’m reading travel narratives and essays on photography. So how I decide what next to read is dependent upon these categories above, which means that sometimes I’m reading about geology or astronomy. I just love to read any and all things.

If you weren’t a writer, what would you do instead?

If I weren’t a writer, I hope that I would have pursued music or opened a school or become a pediatrician.

Jenny Xie, The Rupture Tense

How do you tackle writer’s block?

The concept of writer’s block implies there are stages of creative obstruction that demand unclogging, and that the resuming of writing is the needed release. In own my experience, it helps to remind myself that there are forms of art-making and creative stimulation that aren’t tied to just fastening language to the page. Remaining in silence, absorbing art and thinking that raises one’s temperature, being attuned to vibrations that emerge from complicated entanglements in life and living—these are also vital stages and forms of creative engagement.

What part of your writing routine do you think would surprise your readers?

I resist writing poems longhand. There’s something about the velocity of typing, the rhythmic patter of keys, and the ease of being able to delete, write over, reformat, and see instantaneous edits and changes that makes composing on a computer my preferred medium. I also keep an unsettling amount of tabs open on my browser.

What was the first book you fell in love with?

Encountering Sandra Cisneros’s The House on Mango Street was an early catalytic reading experience. Hearing a young voice narrate interiority with demotic language, and with the abiding power of metaphoric invention, was intoxicating and enabling.

Which non-literary piece of culture—film, tv show, painting, song—could you not imagine your life without?

Sitting in the hushed dark of a movie theater, happily alone yet simultaneously among many, taking in what blazes up on the screen.

What motivates you to write?

What lies outside of narrative enclosure, what eludes telling, the vast reaches of the unlanguaged.

John Keene, Punks: New & Selected Poems

Which non-literary piece of culture—film, tv show, painting, song—could you not imagine your life without?

I’d find it hard to live without any of these artistic genres. I love them all.

What is your favorite way to procrastinate when you are meant to be writing?

Reading. Frequently these days something on the internet (an article, social media, etc.) but usually someone else’s work I admire, a book of poetry, a short story, a creative nonfiction essay, a biography snippet, etc.

How do you decide what to read next?

I often have required reading for my full-time and advisory job(s), so that determines the order of what I read and when I can read for pleasure.

What do you always want to talk about in interviews but never get to?

The ideas and concepts in my work; customarily I am asked about form, style and themes, but I would love to puzzle through some of the ideas and concepts I am trying to explore.

If you weren’t a writer, what would you do instead?’

Something else creative. I drew before I ever wrote a word, so I would probably be an artist of some sort, and a teacher, because I love teaching and working with students and colleagues.

*

TRANSLATED LITERATURE

Jon Fosse, author, and Damion Searls, translator of A New Name: Septology VI-VII

Jon Fosse

What time of day do you work?

I’ve always preferred to start writing right after I wake up so I can move into writing directly from sleep with its dreams and nightmares. Writing is a more or less conscious dream, and that’s how I try to write. The time has changed, though: I used to start at around eight in the morning and write until 1 or 2; for the past ten or fifteen years I’ve woken up earlier, started at five or so when it’s still night, and written until 9 or 10 in the morning. I do sometimes write in the afternoon, but then it is mostly minor corrections; I can also translate well in the afternoon.

How do you tackle writer’s block?

I’ve been a professional writer for forty years now and I have never experienced writer’s block. My first novel, Red, Black, was published when I was 23 years old, and now I’m 63 and I’ve published more than fifty books. My idea is that I have to write my own texts in certain periods, then take a break, and in those in-between periods I can do other things. I used to work a lot as a reader for my publisher; I also wrote prefaces to books, essays for newspapers and magazines, and so on. In recent years I have mostly translated during these breaks, or else I’ve written version of plays, mainly Greek tragedies, for this or that theater.

Perhaps I can also mention that I’ve started to write by hand in the past few years, with a good fountain pen in a notebook with good paper. Actually I switch between different pens and different colors of ink. Writing like that, instead of on a computer, I can write any time and anywhere. It’s a much bigger change than I thought it would be.

What’s the best or worst writing advice you’ve ever received?

I think the best advice I’ve learned from life is to listen to yourself, not to others. Stick to what you have, not to what you want to have or wish you had. Stay close to yourself, to your inner voice and vision and how you want the writing to be.

When my first novel was published it got lots of bad reviews, and they haunted me, and if I had listened to them I would have stopped writing. I decided to listen to myself instead—to what I knew. Ever since then that has been a kind of rule for me.

Of course this goes both ways. For some years now my writing has been well received, and I’ve received many awards and so on, but I try to not let it influence my writing in any way. Good reaction or bad reaction: it doesn’t matter, I stick to what I know, what I feel I need to write, what I can do and not what I want to do. For example, my plays were a great success but I decided to stop writing plays, and I stopped for many years. Instead I went back to where I started, writing my kind of fiction and poetry.

*

Damion Searls

What part of your translating routine do you think would surprise your readers?

I think people are surprised to hear that I try not to read a book before I translate it; I try to save the first reading for while I’m translating. (I say “try” because for some projects, I pitch a publisher myself after I’ve read a book, or else I have to write a report about the book or something before a publisher takes it on.) Whoever reads the translation is going to be reading the book for the first time too, and I want the translation to give readers that experience. I also rarely look back at the original during the last few drafts—at most to check a word here and there. I’m revising to make the English work better, I already know what the original says. What both of these strategies have in common, I think, is that I’m trying to keep my reading experience intact, because that’s what I’m trying to convey or create for others.

If you weren’t a translator, what would you do instead?

I always used to say I would be, or I wish I was, a film editor. I don’t know if it’s the same now with all the digital technology in that process, but when I was younger I always liked the idea. Maybe because it’s the same reactive or responsive kind of creativity, plus with something tactile and concrete to touch and look at.

Scholastique Mukasonga, author, and Mark Polizzotti, translator of Kibogo

Scholastique Mukasonga

How do you tackle writer’s block?

I’m surely an atypical writer. I was made a writer by the genocide of the Tutsi in Rwanda. I didn’t have time to go looking for literary models. I never took writing classes. When I received, on a single sheet of paper torn out of a school notebook, the names of my loved ones who had been murdered simply because they were Tutsi, I understood that I was the only survivor of my village, Gitagata. I was gripped by anguish. I was the only remaining memory of them. Was I going to lose that memory by retreating into silence, or despair, or madness? The least I could do was list the names of those who would never have proper graves. I had to name them one by one, without forgetting a single one. It was the sacred duty of the survivor. And so I began to write, and that list of names on a simple sheet of paper gradually became my first book, Cockroaches, a paper tomb for those who would never have a sepulcher.

What part of your writing routine do you think would surprise your readers?

I wrote my first books in cemeteries. I live in a village on the Normandy coast, and it was there that the D-Day landing took place, on June 6, 1944. The Norman countryside is dotted with cemeteries. One of them, a Canadian cemetery, became my “writing room.” I can still see myself sitting at the foot of a cross armed with a sword (this place is called Sword Beach), with rows of identical grave markers on either side, each bearing the name of a soldier and the insignia of his regiment. According to the register, there are 884 of these markers. There’s a grave I visit as often as I can. On the tombstone it says: A SAILOR 6-7th 1944 KNOWN UNTO GOD. I ask this unknown soldier forgiveness for blending his mourning with that of my loved ones, who will never have graves.

What was the first book you fell in love with?

Books were scarce in Rwanda. In primary school, in Nyamata, the teacher rarely handed out textbooks. There was perhaps one book for two or three pupils. Barely had we finished reading a story than he took back his precious books and locked them in a closet. At the lycée in Kigali, I don’t recall seeing a library. The books weren’t for everyone, but were reserved for the instructors.

Only when I was in exile in Burundi did I finally have a book to myself. I found it abandoned on a table in the minor seminary that had taken in refugee Rwandan girls. It had a beautiful red-and-gold cover and a mysterious title, The Count of Monte Cristo. I borrowed it and never gave it back. At the college for social workers in Gitega, where I remained alone in the empty dormitory, I escaped just like Edmond Dantès from the Château d’If. I dreamed that maybe I, too, could return home and discover a treasure. I didn’t know then that my treasure would be writing.

Which book(s) do you reread?

My bedside reading is Elie Wiesel’s Night and Primo Levi’s If This Is a Man, about the Shoah. These books didn’t serve as models. I discovered them only after writing and publishing Cockroaches. It was reviewers who made the comparison. I was comforted to note that, faced with similar fates, we reacted in the same way. I adopted this statement of Elie Wiesel’s: “For the survivor who chooses to testify, it is clear: his duty is to bear witness for the dead and for the living. He has no right to deprive future generations of a past that belongs to our collective memory.”

If you weren’t a writer, what would you do instead?

Becoming a social worker was probably the only choice I’ve made in life. When I decided to enroll in the school for social workers in Butare, in Rwanda, I believed that after getting my degree I could return to my village and bring back knowledge to those women who had been barred from attending school because they were Tutsi. I wasn’t able to practice my profession in Rwanda, but I was able to practice it in Burundi and France. After the genocide that murdered my loved ones, I lived with survivor’s guilt. I could easily have tipped into madness. But there were my “charges,” who needed their social worker’s help. I didn’t have the right to be weak.

That profession helped me bear the burden of being a survivor. It’s what gave me back the strength to be useful to someone else, and what allowed me to rebuild my life and to write.

*

Mark Polizzotti

What time of day do you work?

Any time and any place that I can. Since I juggle my translation and writing activities with a full-time job, I have to take my opportunities where I find them. This might be mornings before work, weekends and holidays, or other stolen moments (I’m writing this on a commute). Transportation provides the best opportunities for translating: train rides, air travel, any extended trip that doesn’t require frequent transfers or disruptions. Translation is an art, a craft, a calling, a mission, a job, a sacred trust—and, fortunately, it is one more thing: portable.

How do you tackle writer’s (or translator’s!) block?

One wonderful aspect of translation, for me, is that there is no block: the text is always there, ready to be worked on, endlessly available. Gregory Rabassa quipped that the translator is “the ideal writer because all he has to do is write; plot, theme, characters, and all the other essentials have already been provided.” Translation activates the pure pleasure of language, of working with and playing with and grappling with language. Often, if I’m concurrently engaged in a piece of writing and I find myself stuck, translation is what breaks down the block, by granting me reentry into the matter of language, its mysteries and inspirations.

What’s the best or worst writing advice you’ve ever received?

When I was first starting out as a publisher, I was taken aside by a slightly more senior colleague and warned, in well-meaning tones, that if I wanted to succeed in this business, I should be prepared to devote myself to it exclusively and give up that translation nonsense. In the years since, I’ve translated over fifty books, written a dozen, and maintained a long career in book publishing. But the main thing is, the more I continued to translate and write, on the one hand, and to edit, on the other, the more I found that these activities cross-pollinated one another. Editing sharpened my writing; writing improved my translation; translation made me a better editor: they’re all facets of the same activity.

Which non-literary piece of culture—film, tv show, painting, song—could you not imagine your life without?

Film and music have always been essential to me; I couldn’t imagine life without them. As a writer, some of my most enjoyable projects have been on those two subjects. The famous saying, attributed to everyone from Frank Zappa to Martin Mull to Elvis Costello, is that “writing about music is like dancing about architecture,” and that applies to cinema as well. For me, film and music fill a crucial emotional space, and the best way I know of engaging with them is to just keep dancing.

What is your favorite way to procrastinate when you are meant to be working?

I seem to recall reading once that John Updike could not start his writing day without first polishing the doorknobs in his house. Apocryphal though it might be, it’s as good a delaying tactic as any. For me, it could be household chores like cleaning the apartment (always with music on), or it could be taking a long walk if the weather is too seductive to stay inside. The point of procrastination is to give yourself air and room to breathe, space for thoughts to begin formulating and fornicating—without which any writing is bound be empty and insubstantial, and eventually discarded.

Mónica Ojeda, author, and Sarah Booker, translator of Jawbone

Mónica Ojeda

What time of day do you work?

It changes for every book. I wrote Jawbone at very different times of the day because I didn’t have much time and I was very obsessed with it. I couldn’t let it go, couldn’t stop writing. And now I’m working on a new novel and I’m writing only in the mornings, because of the light. For this book I need natural daylight.

What’s the best or worst writing advice you’ve ever received?

To live dangerously. It was not said as a metaphor, but literally. And I think that to write I need the opposite: to live calmly, slowly.

Which non-literary piece of culture—film, tv show, painting, song—could you not imagine your life without?

My life would be definitely worse if it wasn’t for ”Tonada de luna llena” de Simón Díaz.

What was the first book you fell in love with?

Moby-Dick. Before I didn’t know what love was.

Which book(s) do you reread?

Sollozo por Pedro Jara de Efraín Jara Idrovo and El libro de las preguntas de Edmond Jàbes.

*

Sarah Booker

What time of day do you work?

I am generally able to turn to translation in the late afternoons and early evenings. This tends to be my most productive time of day, when I work best. It is also when I’m not doing my other job, which is teaching.

How do you tackle writer’s (or translator’s!) block?

To be honest, translation is often my cure for blocks on other kinds of work, be that lesson planning or academic research. However, when I find myself stuck with a certain part of a translation, I try to switch gears by revising other sections of the book, doing a very quick and dirty translation of a new section, or just moving to a different chapter.

Who is the person, or what is the place or practice that had the most significant impact on your literary education?

My dad, who was a botanist but also a lover of literature. I have such clear memories of talking to him about books, such as the day, when I was a teenager, that he told me about Gabriel García Márquez’s One Hundred Years of Solitude in Gregory Rabassa’s translation and showed me the complexity and beauty of the novel’s opening sentence. It made me look at writing in a new way.

What is your favorite way to procrastinate when you are meant to be working?

Cooking elaborate dishes that just barely resemble the original recipe.

What book has elicited the most intense emotional reaction from you (made you laugh, cry, be angry)?

Mariana Enríquez’s Nuestra parte de noche (Our Part of Night in Megan McDowell’s translation) elicited a lot of intense emotions. The story and writing really clicked for me, but I also read it during the very early days of the pandemic when everything had a different intensity to it.

Samanta Schweblin, author, and Megan McDowell, translator of Seven Empty Houses

Samanta Schweblin

Who do you most wish would read this book? (your boss, your childhood bully, etc.)

I hope my ex-mother-in-law doesn’t read “Two Square Feet.” She was the one who told me the story of how she sold her wedding ring and what she used the money for, asking me to please never tell anyone about it. Luckily, hers is a family that doesn’t read much literature.

Who is the person, or what is the place or practice that had the most significant impact on your literary education?

My maternal grandfather. He gave me my first collections of stories by Borges and Julio Cortázar, and he was the one who encouraged me to write too. First a diary, which we started together when I was around seven years old, recounting the impressions of the day and the walks we took together. Later, something very similar to writing fiction: we read poetry, and we wrote in the diary only the words or the lines that caught our attention the most, generating something new that we used to read out loud.

What part of your writing or translating routine do you think would surprise your readers?

Okay, this may sound a bit silly, but I can’t write a word if I don’t tie my hair up in a ponytail or bun first. No matter how much I’m going to write, I need my hair to feel taut, as if I were just about to run a marathon.

Which book(s) do you reread?

Far Away From Home is probably the book I’ve read the most times in my life. I don’t know if it’s my favorite book, but I read it for the first time when I was a teenager, at a very special moment in my life when I felt strong, open to everything strange and unknown, open even to the possibility of the pain that could come with the adventure of living life fully. It is a book that brings me back to that place. His poetry cradles me, his darkness brings me back to my feet. It is like medicine for the soul.

What is your favorite way to procrastinate when you are meant to be working?

Eating toast with butter (this is an ideal combination, because you have to wait about two minutes for each piece of toast), and learning new German vocabulary that I will probably forget two days later. Sometimes I do both at the same time.

*

Megan McDowell

Which non-literary piece of culture—film, tv show, painting, song—could you not imagine your life without?

The album 69 Love Songs by Magnetic Fields. It came out when I was in college and I’ve listened to it ever since, it’s been with me in every life I’ve lived since then. It’s like it doesn’t age and it fits in any context, time, or place. It’s also the best road trip album, because I know every word and can sing along at the top of my lungs.

What was the first book you fell in love with?

It’s hard to reach back through the haze and remember chronologically… It could very well have been The Secret Garden, or Little Women, or The Lion the Witch and the Wardrobe. Let’s go with The Secret Garden. I fell in love with it because of its atmosphere of mystery, and because the main character, Mary, was a little girl but had so much agency and freedom. In retrospect, I think I liked that Mary wasn’t always the sweetest of girls, and I think I fell in love with both Dicken and Colin, who were so different from each other but both so alluring. And I just fell in love with the garden itself—when you’re a child, the idea of a magical world of your own is so tantalizing.

If you weren’t a translator, what would you do instead?

I romanticize being a dancer. Translating is so sedentary, I would love to do something physical and beautiful. But I know it’s a hard life, and it’s hard on the body. I guess really I would like a job that would help people, like maybe an immigration lawyer or an investigative journalist or a social worker.

Who is the person, or what is the place or practice that had the most significant impact on your literary education?

This could only be my parents, who read to my sister and me when we were little, and took us to the library and to bookstores and got us excited about reading, and didn’t even object to us studying Literature in college, though we had no idea what we were doing. Also my sister, who would read side-by-side with me and made it so reading was never a solitary endeavor.

What is your favorite way to procrastinate when you are meant to be working?

I find myself doing housework instead of working—it’s at least useful, I tell myself, better than Instagram. Procrastination is the only way any cleaning gets done at my house.

Yoko Tawada, author, and Margaret Mitsutani, translator of Scattered All Over the Earth

Yoko Tawada

What time of day do you work?

I work every day right after I get up until I can’t anymore. (Sometimes I can work only 2 hours, but sometimes longer). This time zone is good because the dream logic has not disappeared completely and I am not yet a decent citizen who pays all bills on time and does not forget any doctor’s appointment.

Which book(s) do you reread?

• Franz Kafka, The Hunger Artist

• Ingeborg Bachmann, Malina

• Fyodor Dostoevsky, all novels

Which book will you read next?

Thomas Mann, The Magic Mountain

*

Margaret Mitsutani

Which non-literary piece of culture could you not imagine life without?

Randy Rainbow’s parody songs, especially his response to Ron DeSantis’s “anti-gay bill,” which contains the line “let’s bask in the splendors of all shades and genders.”

What is your favorite way of procrastinating when you are meant to be working?

Recently I procrastinate by reading news about the midterms, especially in my home state of Pennsylvania. This is very distracting, because the stakes are so high. The Republican candidates for governor and senator are, respectively, a wackadoodle who is a genuine threat to democracy, and a conman whose marks are primarily women.

If you weren’t a translator, what would you do instead?

I’m too old to think about doing something entirely different, but if I hadn’t been constantly told that “girls don’t do science” when I was younger, I would have liked to try my hand at paleontology. I’ve always been fascinated by dinosaurs and trilobites.

*

YOUNG PEOPLE’S LITERATURE

Kelly Barnhill, author of The Ogress and the Orphans

What time of day do you write?

My writing times are inconsistent and random. I have always admired the people who are able to keep regular hours and predictable patterns—it seems like a great way to live, honestly. But for me, I find that the harder I press myself to operate with anything veering on regularity, the more my foundations resist it. I am a flighty, flaky author, I’ve realized. My organizational skills are terrible and my follow-through is worse. I don’t write every day, and never have, though I often wish that I did, or could. I have probably thousands of partially drafted and abandoned essays, novels, short stories, graphic novel scripts, and plays scrawled in random places and stuffed into drawers in my office. I don’t remember starting most of them.

When I do write, it feels like a miracle. And when I finish something—a bigger miracle. I always treat each of my projects as potentially the last I’ll ever do, because it always feels either like a genuine possibility, or overwhelmingly true. And there’s something to it, actually—finishing each book as though it was your last. It allows us to offer our full selves to each project and leave nothing at all behind. It allows us to accept that each book is a gift—both from us and to us—and our task is to be obedient to the work, and grateful for the work, and to be unbothered about whatever might happen next. I write these words absolutely thinking that perhaps I will not write another book. And maybe that will be true. We’ll see.

How do you tackle writer’s block?

Writer’s block is just the brain’s way of telling us that it needs rest and care. It needs food and diversion. It needs to be given other tasks and work other aspects of itself in order to continue the work of creation. I don’t think that any good comes from grinding ourselves to dust. If we can’t write, we can’t write, and that’s okay. Take a walk. Read a book. Sit on the grass and allow the self to be still as the great world spins.

Occupy your thoughts with beautiful things and find people and animals to cling to—preferably while lounging on a couch in a tangle of limbs and smiles and having delightful conversations and constant demonstrations of affection. If the urge to pin words to the page returns, that’s great. If not, oh well. I know this is a minority view and other writers—all much more productive than I—have a different approach. Personally, I choose not to stress about the absence of creation and the absence of work. Fields need to lie fallow every now and again in order to produce, and so too with us.

What’s the best or worst writing advice you’ve ever received?

I once met a writer who told me to keep a rubber band on my wrist and snap it every time I found myself pausing and possibly missing my desired per-hour word count. I did not take this advice, and I do not advise it. Another author encouraged me to keep a small bowl of chocolate chips on my desk and to have one every time I finished a page. This I did try, and don’t recommend. Too sticky. And it’s hard to get chocolate out of the gaps on your keyboard.

Which non-literary piece of culture—film, tv show, painting, song—could you not imagine your life without?

Can I say the 1999 classic film, Galaxy Quest? You know what? I don’t care what you people think. I’m saying Galaxy Quest. If there is a more perfect movie that exists on earth, I have not found it, and I defy anyone who tries to tell me otherwise. No movie gets quoted more in my household, likely because we have the whole thing memorized.

How many times have we watched it? God if I know. Maybe a thousand. Maybe I’ll see it a thousand more. And if I do, it’s time well spent. Is it silly? Obviously. And that’s the point: I think we’d be happier as a nation if we uplifted more silly, beautiful things. I’m not sure why we’re still discussing this. Maybe we should all watch Galaxy Quest instead and we’ll all have wonderful day.

Which book(s) do you reread?

My favorite reading is rereading. I reread Howl’s Moving Castle almost every year, usually in the early spring, though I don’t know why. It almost feels primal—like a fish returning to the ground of its making so it can continue making. I reread The Shipping News quite often, and for reasons that should be obvious, I started rereading Octavia Butler’s duology of parables during the grim Trump years. Karen Joy Fowler is another author I return to more often than not. Lately, I’ve been rereading Terry Pratchett’s Discworld books, though not in any pattern or theme. I reread them randomly, following my own curiosity and comfort and joy. I think, for me, that’s the biggest draw of the reread, that its only purpose, really, is to return us to joy.

What is your favorite way to procrastinate when you are meant to be writing?

I take my dog to the woods and we walk, sometimes for hours. Sometimes we stay out all day.

If you weren’t a writer, what would you do instead?

Before I was a writer, I was a teacher, and maybe I would do it again, despite the current nationwide cruelty towards teachers. I also had done work as a janitor, activist, bartender, park ranger, receptionist and phone book delivery gal, and maybe I’d do any of them again. Except maybe the phone book thing. I was a pretty good janitor, honestly. And activism comes pretty naturally. Bartending is great for anyone who tends to be gabby—and I have plenty of that. I think it’s possible that the park ranger ship has sailed, if for no other reason than the fact that there aren’t a lot of jobs available in that department, but I did love it.

And when I was a receptionist at a law firm that didn’t get a single client calling or walking in the whole time I was there, and I’m fairly convinced that the whole thing was just a front for organized crime, what I loved most was that I had the freedom to just read all day. And that’s what I did. It’s not a bad way to make a living.

Sonora Reyes, author of The Lesbiana’s Guide to Catholic School

How do you tackle writer’s block?

When I have writer’s block, it almost always means there’s something else going on that needs to be solved before I can continue writing. First, I ask myself if my basic needs are met. Have I eaten, had enough water, enough sleep, etc.? Then if all those needs are met, I ask myself if I’ve been overworking myself.

Sometimes I find that writer’s block is just my body’s way of telling me I need a break. I think the best thing to do in those cases is to be nice to myself and get some rest. Finally, if none of that is relevant, then the last thing I do is talk out my next scene with a friend. Usually talking out the very next thing I need to write either helps me get motivated to write it, or makes me realize there’s a problem or plot hole that needs to be addressed before I can move on.

What’s the best or worst writing advice you’ve ever received?

The best writing advice I ever heard was to not expect a first draft to be perfect, or even good. That a first draft is the ingredients of your favorite pie. The ingredients themselves won’t taste good right away, but they are all necessary in order to bake that perfect pie.

What is your favorite way to procrastinate when you are meant to be writing?

Talking about writing. Sometimes it’s a good form of procrastination, because it can help to motivate me to actually write if I get excited enough about it. Sometimes, though, it’s just a way for me to feel like I’m being productive without actually having to write.

What book has elicited the most intense emotional reaction from you (made you laugh, cry, be angry)?

Don’t Date Rosa Santos had me crying from every kind of emotion you can imagine. I felt so seen by this book. It was a lovely read and I highly, highly recommend it!

What do you always want to talk about in interviews but never get to?

Books that are nowhere near being published yet. I write very fast, so each book has at least a few years to sit before it eventually gets published. I would love to be able to scream about how excited I am about whatever book I’m currently outlining or drafting in the moment. Luckily I have a few good friends who will keep the secrets for me.

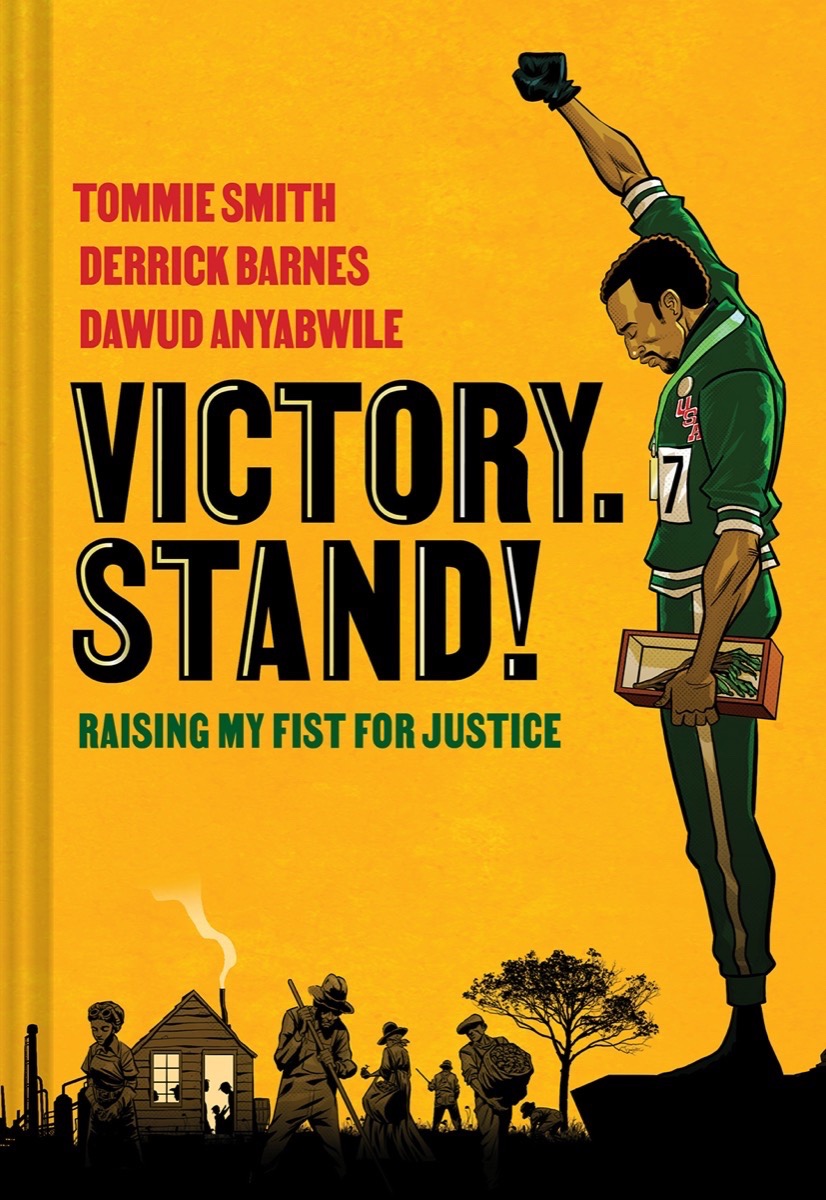

Tommie Smith, Derrick Barnes, and Dawud Anyabwile, authors and illustrator of Victory. Stand!: Raising My Fist for Justice

Dawud Anyabwile

Do you ever experience artistic blocks? How do you get past them?

Yes. In fact I have them all the time. Sometimes I have to do something else and then come back to my work or I may study the works of artists that I admire whose style may be similar to mine. I see how they figure out techniques or ideas that I may be stuck on and it gets me excited. Once I start working again I forget about their work and my ideas come into the forefront again.

Who is the person, or what is the place or practice that had the most significant impact on your creative education?

I would say both of my parents however my father inspired me in many ways that encouraged me to be bold about what I choose to do but my mother was a musician and creative person so she had more of an understanding of what I needed creatively and helped me to pursue my interests in the arts. My father was. backup support and did the same in other mediums that helped with me obtain my goals.

What is your favorite way to procrastinate when you are meant to be working?

Producing music is not really procrastinating because I am still creating, however, I always had to make a choice between music production and art so when I take a break from drawing I like to jump into the music.

What do you always want to talk about in interviews but never get to?

My interest in music production, the hip hop early years and its impact on my fine art career.

If you weren’t an artist, what would you do instead?

That is difficult to say since I was born with an interest in creativity, however, as an adult, I think I would say I would be very much interested in real estate and travelling the world.

*

Derrick Barnes

Who do you most wish would read this book? (your boss, your childhood bully, etc.)

I hope that it’s the kids that are right on the verge of using their voices to make a difference in their schools, on their block, in their cities, etc. The kids that are ignoring all of the silly book bans across the country and doing their due diligence by reading everything they can about marginalized people, absorbing every book on every banned list and then taking action, in whatever form that action presents itself, to make the world a better place for everyone.

What time of day do you work best?

I work best between 9:30 PM and 1 AM. We have a large family (four boys), and so there has always been a lot of life, a lot of activity going on in our house. So for years, I got accustomed to getting started as soon as everyone went to bed. The night time just became the right time to create.

Why did you decide to write this book?

It fits right into my wheelhouse, right along with the body of work I hope I’m building to reflect Black brilliance, Black beauty, Black defiance. Telling the story of this magnificent, American sports hero, and thee most iconic sports protest image in the history of this country was a privilege. This book, this story was meant for me to tell. Most definitely on brand for me.

What’s the best or worst advice you’ve ever received?

Some of the best advice that I ever received was from one of my mentors, Mr. Wade Hudson. When my career was struggling, and I seriously considered never writing again, he told me to keep cranking out ideas, keeping crafting books as if I had contracts on the table. He told me that it’ll only take one book. That’s it. And he was right. After my eighth book, and seemingly just scratching the surface after thirteen years, I wrote the book that changed my life—Crown: An Ode To The Fresh Cut. Don’t stop. Keep pressing forward no matter what.

Who is the person, or what is the place or practice that had the most significant impact on your education (creative, cultural, athletic, academic, or otherwise)?

Two places in particular: my hometown of Kansas City, MO and my alma mater, #theeilove—Jackson State University. Being from KC, which is a quintessential midwestern city, populated by blue collar, hard-working folks, the best barbeque on the planet, and is one of the birthplaces and stomping grounds of jazz and jazz giants such as Charlie “Bird” Parker. Kansas City has a lot of soul, seeing how it was one of the northern cities for over six million southern Black people looking to escape terrorism, wicked racism, and poverty to ‘escape’ to during the Great Migration (1910-1970). My family was a part of that migration.

At Jackson State, I was officially added to the lineage of game changing, culture shifting, brilliant beautiful Black folks to not only come from that great institution, but from every HBCU in America. I met the love of my life there, met lifelong friends that I consider brothers, and I also earned my first paid writing gig, penning a column for the Blue and White Flash, which helped me to land a job at Hallmark Cards as the first Black male copywriter in the history of the company. The rest is history, baby.

What do you hope young people will take away from this book?

I hope they take away the ideal that sometimes, just as Dr. Smith did, even when we know there may be a negative backlash, that we may have to sacrifice ourselves for the greater good of the society. I want them to understand that they don’t have to be from a family of civil rights leaders to make a difference, to have a voice. Simply utilize the gifts that God has blessed you with in order to connect people, to be a rabble rouser, to stir things up, to make positive and necessary change.

Which non-literary piece of culture—film, tv show, painting, song—could you not imagine your life without?

Music. Period. I love, love, love jazz music. It fascinates me more than any other art form. To be able to tell a story, to paint a moment, a scene, without the very use of my primary tool of choice (words) is absolutely amazing to me. John Coltrane is by far my favorite creative of all time, and forever.

What was the first book you fell in love with?

The Best of Simple by Langston Hughes, fifth grade, Mrs. Shelby’s class.

Which book(s) do you reread?

Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave, The Spook Sat By the Door by Sam Greenlee.

What piece of art (literary or otherwise) has elicited the most intense emotional reaction from you (made you laugh, cry, be angry)?