In the Wake of Films Like Avatar and RRR, 3-Hour Movies Are Here to Stay

Posted by admin on

Hollywood, it’s time to release movies that are cut to the length they deserve: 3-hour movies are here to stay.

As a huge fan of movies, I’m starting to wonder if major studios, audiences, and filmmakers are all on the same page when it comes to turning off the clocks. “Just another hour” is a phrase I’m hearing less and less, especially when some of the best recent movies have more than enough time to take on a life of their own.

Avatar: The Way of the Water is James Cameron’s latest sci-fi epic, which clocks in at a whopping three hours and 12 minutes (for good creative measure). Craving a Hollywood blockbuster, I had the pleasure of watching Avatar 2 three times in different ways. The movie was the same as I expected each time: flashy explosions, soothing blue lighting, and effects that sold 3D TVs for a time. The longer running time showed me three types of viewers who can put their lives on hold (without moving) for 180 minutes.

My first screening – like most movies that draw me straight to the theatre – was the most liberating one. I had no one to complain to, no one to worry about with my own disciplined silence. There’s a doable, indulgent power in being able to escape civilization for a few hours (and what better way to do that than in a dark, soundproof box?).

My undivided attention allowed me to sit through the motions of carefully slow-rolled cinematography. I meditated with open eyes to appreciate Cameron’s immersive planet, presented like a part-documentary.

It was exactly a year after I met Cameron virtually at a Zoom press roundtable, where he shared his storytelling sauce for his personal art book, Tech Noir. Simply put, this was a director who didn’t want to be creatively constrained and hated compromise. Cameron’s sequel was a vision he preferred to tell once and save for a director’s cut later. Better yet, he would put his foot down – but never in front of the audience he had in mind.

According to Entertainment Weekly, Cameron’s thoroughness in telling his full version of Avatar: The Way of the Water broke the vices of investors, including Disney, who spoke for the majority of uninitiated viewers about length. To put it bluntly, it was a gamble to release an overdue sequel in a world that has moved on to bite-sized installments.

“Avatar: The Way of Water brought out audiences that could look past an IMAX screen and see Cameron looking back in mutual appreciation.”

Of course, audiences could tell Avatar: The Way of the Water wasn’t rushed. My solo screening was an aptly stimulating three hours of my time and $35 (with a Number 1 combo). My personal contribution somehow added to worldwide box office figures that put Avatar: The Way of Water fourth on the list of highest-grossing movies of all time (which hilariously sits under Titanic – another Cameron film with the same approximate runtime).

At the very least, I took a break from my dwindling Fanta sips and sat in Cameron’s mind for 192 minutes. Avatar: The Way of the Water brought out audiences who could look past an IMAX screen and see Cameron looking back in mutual appreciation. For a full three hours, audiences saw the director’s creative vision at eye level.

But The Way of the Water still isn’t exactly the greatest movie ever made, no matter how many times I’ve voraciously subjected myself to it. It’s still chock-full of filler, a problem that has spawned entire episodes of longer TV series. In Cameron’s feature-length movies, his own filler scenes can make your knees go numb or shake uncontrollably.

A second screening showed me a casual kind of viewer which could be sold on the idea of “more movie. My parents – casual but experienced moviegoers – had the honour of seeing The Way of the Water with me 13 years after its predecessor. One of the problems with seeing a movie is that I live vicariously through the first-time viewers next to me. In this case, my parents (both in their 60s) didn’t flinch or ask me questions a filmmaker would be better suited to answer.

“It was stressful,” my dad simply told me, after I was impressed that he had sat comfortably in a warm, dimly lit hall for three hours without taking a nap.

He cited Cameron’s ability to reunite audiences with characters like Jake Sully, Neytiri, and other familiar faces. But he makes viewers nervous by putting them in new life-or-death situations that could mean any favourites could be wiped out in the next frame. My dad was on the edge of his seat for three hours, with bursts of tension evenly spaced. This was movie pacing put to the test for my parents, who had evolved through decades of two-hour movies and seen cinema change.

I’m happy to report that Mom and Dad loved Avatar: The Way of Water, just like many audiences who can brag about watching a three-hour-long movie. To my own satisfaction, not a single snore was vibrated by someone inside the IMAX hall that day.

“Nobody and everybody wins in a three hour screening.”

My third screening of Avatar: The Way of the Water was by far the most nerve-wracking.

I’ve already mentioned my ability to keep all thoughts and excitement to myself when there’s no one around. In this case, a few long-time (anonymous) companions who would follow me to the ends of Canada – and at least to the credits of a three-hour movie. I couldn’t exactly live vicariously through their reactions, much to my own habits of projecting joy. This was where I met the viewers who made short work of Netflix series and had control over their pacing.

Halfway through the whale oil scene, my friend on the left leaned into my ear, Godfather-style, with a most perplexing question.

“How much time is left?” he asked, like any sane viewer of less than a handful of extended movies. In my mind, it was the cinematic “Are we there yet?” of the end credits. It was only a matter of time before someone in the audience cracked under the strain of a three-hour running time. While Avatar: The Way of the Water was a bit out of its element, born on the other side of a pandemic that made 45-minute webisodes more conditioned.

For the record, no one and no one wins in a three-hour screening.

The applause for three-hour movies in Hollywood (and beyond) shows a clear appetite for it. Nothing would stop audiences from devoting an eighth of their day to RRR, the 2022 Indian/Telugu epic that is also the country’s most expensive production to date. I highly recommend anyone with a Netflix account to try their luck at a three-hour movie with RRR. The movie, directed by S.S. Rajamouli, isn’t new to viewers, as three hours is a standard in South Asian cinema.

“No page in the screenplay was unturned to make RRR a thesis that does more – with even more.”

To be clear, critics and audiences didn’t love RRR for its three-hour length. But the way Rajamouli, the writers, and cinematographer K.K. Senthil Kumar made the audience lose track of time. The movie is centred around a fictional story of two real revolutionaries. RRR entertains the audience throughout with the adventures of Alluri Sitarama Raju (Ram Charan) and Komaram Bheem (Rama Rao). Without giving too many spoilers, three hours are devoted to the growth of a strong brotherhood between Raju and Bheem.

The movie scatters a lot of rousing action, which includes CGI animals and an army of two against improbable odds. These scenes – while pulling out all the superhuman stops – make more sense with the unravelling anticipation and buildup. RRR does character development best over time. In this case, the audience is immersed in the intertwined stories of Raju and Bheem.

The two share more than enough screen time in each other’s world (RRR’s extended Naatu Naatu sequence is the height of bromance, infectiously liberating a prejudiced crowd of British colonists at a party). This development takes the audience through the ups and downs of an enduring friendship before it collapses. RRR sticks closely to Raju and Bheem, stacking a house of cards with each thoughtful interaction. Its tragic climax breaks the friendship and feels all the more impactful to the audience who’ve spent so much time enjoying it. In an unparalleled pacing, every musical sequence, every fight and every dramatic exchange added weight to Raju and Bheem’s relationship.

In RRR, the audience watches a house of cards slowly being built before the director pulls the bottom card at the right time. RRR cements its drama by fully developing Raju and Bheem, who don’t realize they’re on opposite sides of a growing war until it’s too late. Audiences will see their fully realized characters put to the test as RRR begins its revolt – complete with large-scale action that best visualizes everything falling apart.

RRR was told for as long as it was worth, without Hollywood’s status quo for express stories. No page in the script was left unturned to make RRR a thesis that does more – with more.

“I’m vengeance,” said Batman in his own three-hour-long self-titled movie.”

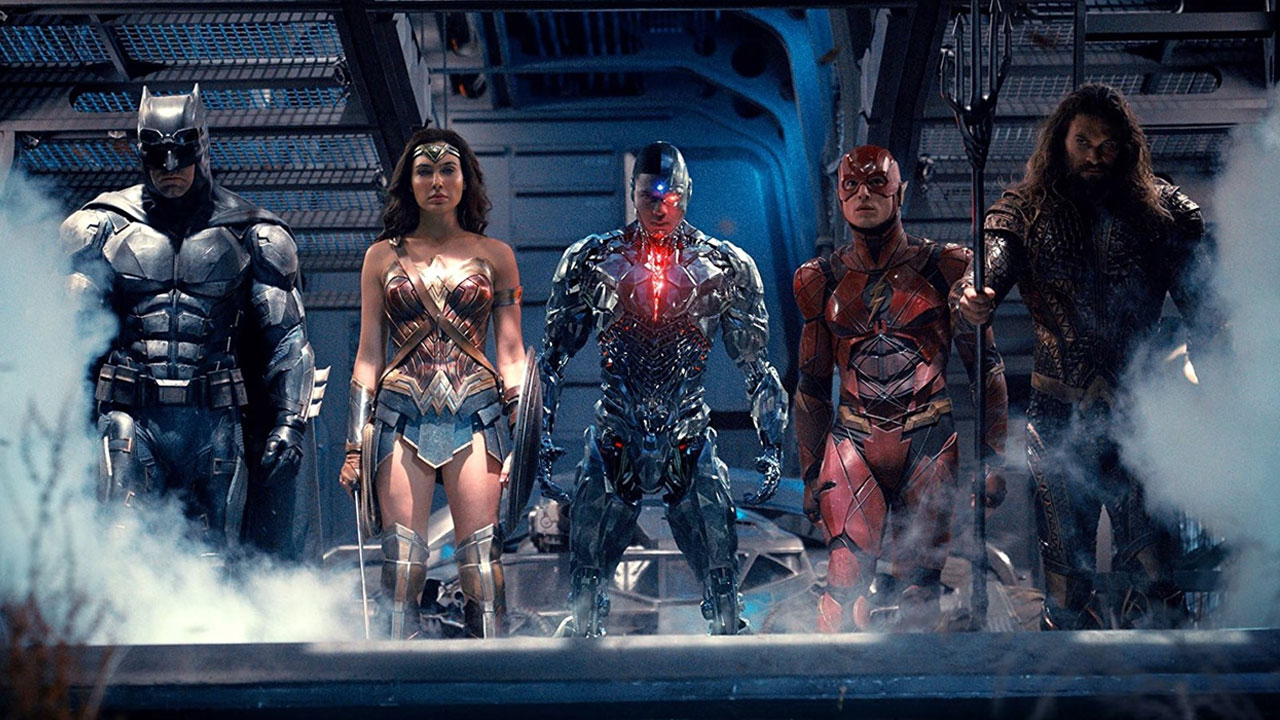

Any attempt to pack something as heavy as a cinematic universe into a single movie is bound to be rushed. That lesson clearly took shape for WB with Justice League, which was helmed by Zack Snyder until his vision was shot down by executives. In a textbook case of made-for-committee production, Snyder’s vision was met with resistance at WB. Its executives were under their own expectations to catch up with Marvel’s hearty, CGI-driven crossover movies. This began with a mandate from former WB chairman Kevin Tsujihara, who wanted nothing more than a two-hour length.

A two-hour Justice League was doable and accomplished, Snyder admitted in a Vanity Fair profile. Ironically, it came at the cost of reducing the heart and humour of Justice League, which WB also wanted. This change in the creative process cut almost all of Snyder’s footage and over 90 minutes of the movies. As audiences would later discover, this footage included character development for The Flash and Cyborg, who played a pivotal role before being relegated to the team’s resident technomancer.

The length of Justice League was key to unpacking six heroes with their own stories to tell in a single project. But the movie fell apart the moment Snyder stepped down as director of the project in 2017, citing his daughter Autumn Snyder’s suicide. Without Snyder’s opposition, WB was able to hire Avengers director Joss Wheadon to reshape Justice League in the eyes of executives. Just as Tsujihara expected, Justice League fit the mould of a finished two-hour movie with six iconic heroes and Marvel’s sense of humour.

Just as WB wanted, their first iteration of Justice League currently sits at an aggregate 39% on Rotten Tomatoes and has grossed over $650 million worldwide. DC’s first major crossover movie also came out weeks after Marvel’s latest Thor Ragnarok, which ended its box office run with $854 million.

Six years ago, I didn’t feel like Snyder’s audience at my local Cineplex for Justice League. In WB’s eyes, I fit their demographic by paying $13 and two hours of my time for their product. But they missed the side of me that was a jaded franchise consumer picking apart Wheadon’s signature brand of CGI and juvenile humour. Right down to Aquaman randomly smashing things and a cheesy frame of the Flash waking up on top of Wonder Woman. Whimsical moments like these were sprinkled in to try and keep my synapses firing between the CGI fights.

But all I saw was more gray paste created by WB to feed hungry fans and send them on their way. It’s food without thought.

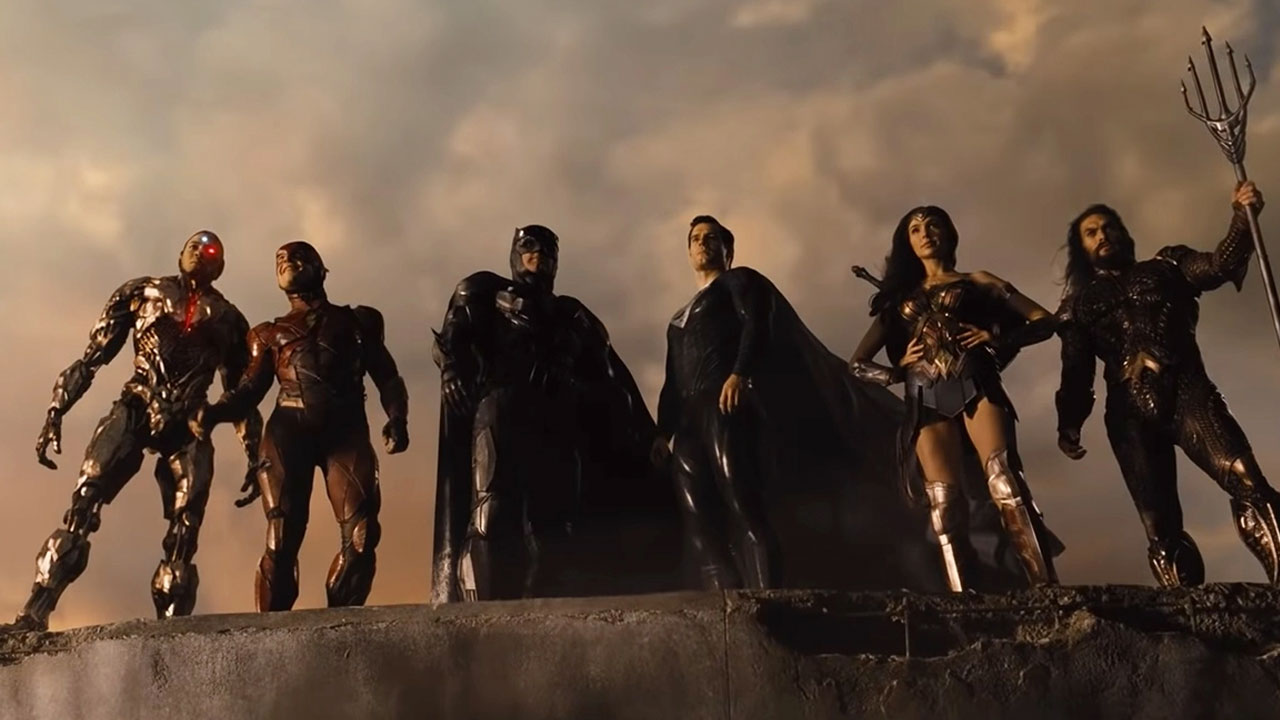

Every criticism from disappointed fans added another character to the #ReleaseTheSnyderCut movement. DC’s outspoken fans rallied with renewed interest in Zack Snyder’s original vision of Justice League. This was the final straw that sent WB’s disparate cinematic universe into an existential crisis. In the years that followed, DC’s cinematic canon had to rely on its own solo movies, which fared better.

All the while, Snyder waited for closure with the support of fans waiting for his cut. Actors like Ray Fisher, Ben Affleck, and Gal Gadot rallied with their own passive sparks to rewrite a page in the DCEU’s tumultuous history. The rushed presentation of Justice League couldn’t be completely erased until November 2019, when WB’s acting executive Toby Emmerich approached Snyder. Zack Snyder’s Justice League didn’t have to be the best superhero movie ever made. It just had to be a better one than the one the money suggested. A longer, unchained cut more than put WB, Snyder, and legions of hurting fans back on a brighter timeline.

Snyder’s finished product clocks in at 242 minutes. At four hours and two minutes, Zack Snyder’s Justice League more than strikes at the heart of WB’s former mandates. The movie featured six acts, which eased viewers into the long running time. More perplexing was the team’s believable character development. Part of the movie is rebuilt around Victor Stone, who undergoes a tragic transformation into Cyborg. The subplot adds a touch of human emotion to the larger-than-life team.

Zack Snyder’s Justice League shows a less glamorous side of being a hero that WB was afraid to touch. But channelling the slow burn of Watchmen (2009), Snyder redeems Cyborg as a troubled athlete with an absent father. Cyborg is a reminder of what each of the older heroes once were – human.

The extra time gives more purpose to the villain Steppenwolf, who captures the Mother Boxes in fear of Darkseid’s retribution. The larger-than-life villain in question is given more than enough time to loom over the Justice League as a Thanos-like threat. Snyder even takes time to develop Darkseid with a flashback and some nightmarish worst-case visions that deepen the stakes. Viewers fresh off the Ultimate Edition of Batman V. Superman might appreciate Justice League for exploring Superman’s death. Snyder’s extra time is also devoted to telling the aftermath through Lois Lane and Martha Kent in an extended scene.

To keep the closure in perspective, Snyder’s revealed cut sits at 71% on Rotten Tomatoes, with critics and relieved fans embracing it over the original cut. Longform storytelling was the first domino to fall with Snyder’s creative vision. James Gunn would reinvent Suicide Squad before unleashing John Cena’s Peacemaker over eight HBO Max episodes. With The Batman, Matt Reeves was given only a PG-13 mandate and an empty hourglass to fill with film.

Three-hour movies aren’t an alarming sign of extra commitment or a daunting task in the theatre. Instead, it’s a director’s love language for showing and telling the audience everything. The audience can still critique a film as it is. But the carte blanche that major studios give directors marks a shift in filmmaking. The value of a movie isn’t just in its length. While there’s an art to making every second count without losing us in the director’s purest vision.

Long live the three-hour movie and the creative freedom to justify it.