Face to Face with the Past: Collecting Civil War Portraits

Posted by admin on

The young men in the photo could not have been older than 20, maybe 25. You can see their youth in their eyes, the older on the left with a steely resolve and defiance in his expression, carefully dressed in his Confederate grays. Clearly the younger of the two, the boy on the right has a sadness in his eyes, a fear belied by his firmly-pressed lips. The younger wears Union blue, the uniform arms too big on his small frame. Not only did both men casually hold their sabers, exposing but a flash of steel, but my attention as well.

I had traveled back to my hometown to celebrate my birthday. I found myself at the New Orleans Museum of Art, staring at Civil War photographs. While little memory remains of any other images from this exhibition, I still remember those two young men, even though nearly six years have passed. There is a certain appeal to old portraits, particularly those from the early days of photography. This rare glimpse into another time somehow feels close and yet unimaginably far away. In the years since, I have learned that I am not the only one who has fallen victim to this appeal. There is a very active set of collectors for Civil War images, particularly portraits.

Photograph and the Civil War

The Civil War was the first major American conflict to be thoroughly photographed. The technologies used for many images, notably the ambrotype process, had only been around for a scant decade before the first shots were fired. But, realizing the role photography could play in documenting the conflict, cameramen were there from the start. They followed the troops from the Union’s 1861 defeat at Bull Run to Lee’s surrender at Appomattox in 1865. This widespread coverage is partly due to an immigrant photographer with a keen eye for opportunity, Mathew Brady.

While few details of the early years of Brady’s life exist, we know that he opened a portrait studio in New York City sometime around 1844, near Broadway. He quickly found success producing portraits of New England’s upper-crust. Within a decade, he had established a second studio in Washington D.C. His studio space was tastefully decorated with his photographs of noteworthy persons. Brady also employed a slew of studio assistants. Some handled the finishing of prints, and a handful of photographers did much of the heavy lifting, notably James Brown, George Cook, Timothy O’Sullivan, and Alexander Gardner.

A true entrepreneur, Brady saw the Civil War as another opportunity to market his business and services, so he jumped at the chance to photograph the conflict for the press. During the war, he would act as an impresario, organizing and overseeing his team of photographers in capturing and distributing images from the battles. While most of his team’s photos were of the battlefields, they also produced portraits of those involved in the conflict.

The Portraits

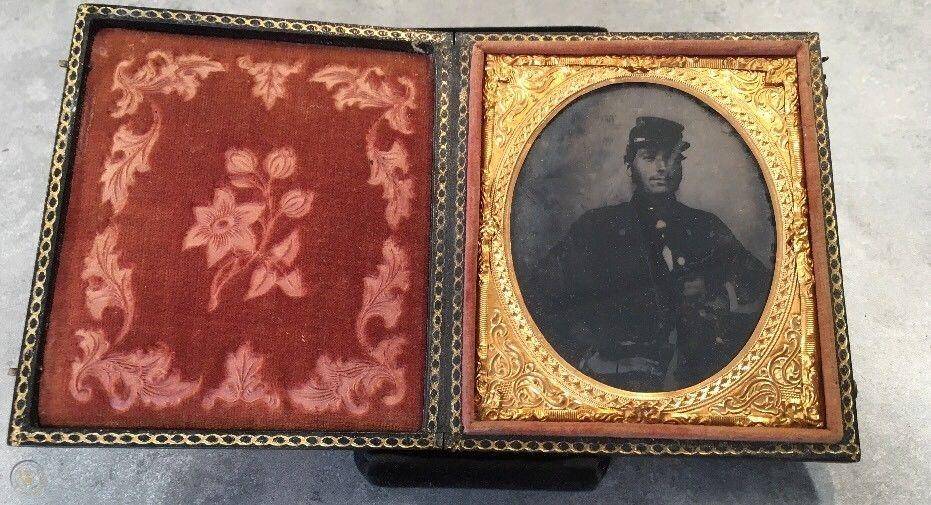

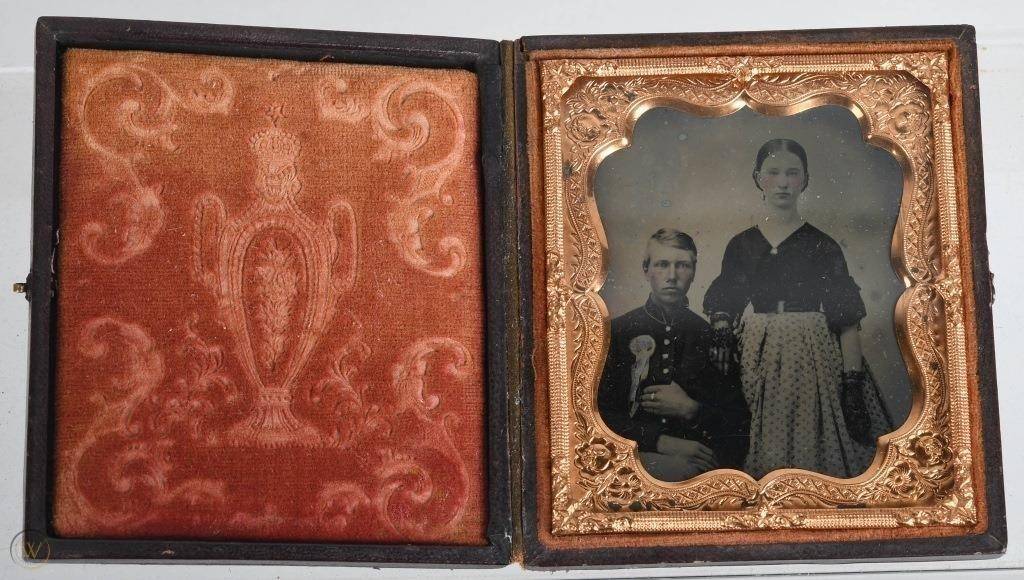

Portraits were often made before leaving for war or traveling between fronts. These images often included individual soldiers in various states of dress. Others included soldiers with their families or other individuals touched by the conflict. The photos were typically ambrotypes, tintypes, or small card-mounted images called carte-de-visite.

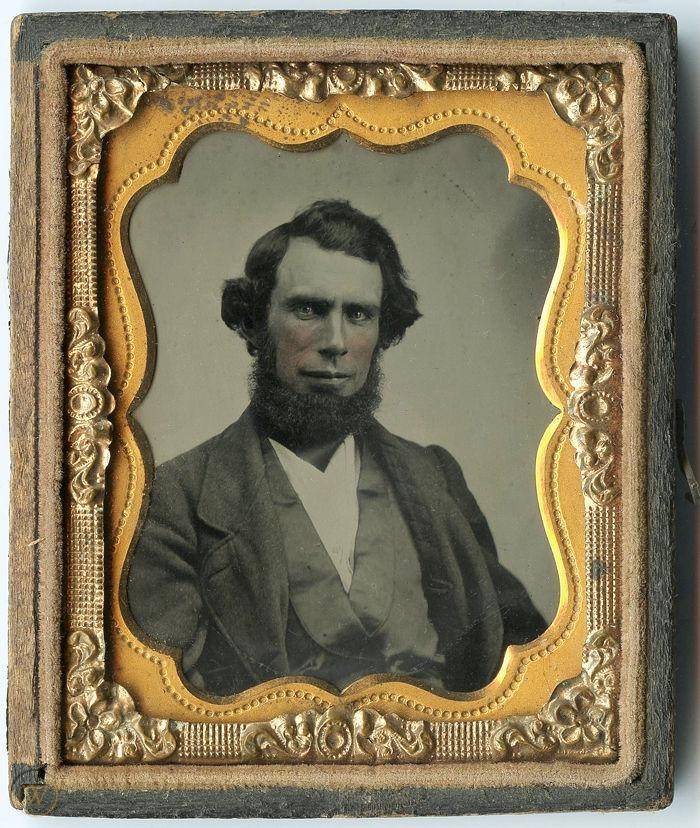

The cheapest images to produce, carte-de-visite portraits, are less sought after by collectors, given that they can be challenging to find in good condition. Ambrotypes, which account for most images from the early years of the war, are made by painting a photo emulsion directly onto a small pane of glass. This coated glass would then be inserted into the camera. Next, the exposure was done directly onto the emulsion, creating an inverted image. When the glass photograph was placed against a darkly-colored backing plate, the portrait would spring to life.

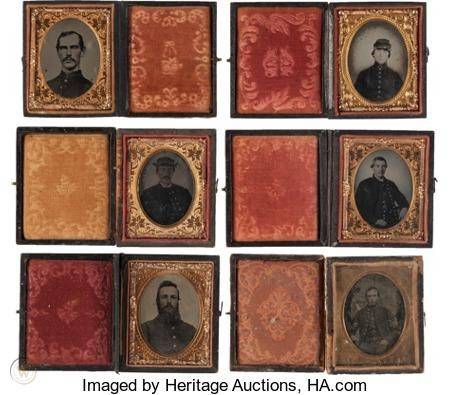

Tintypes were made by painting an emulsion directly onto a thin piece of metal and exposing the emulsified tin (hence the name). Tintypes were hardier than ambrotypes, as the fragile glass needed for the latter could often be broken. A vital part of the appeal of these images, though, is their book-like protective cases. Usually covered in embossed leather, these small, hinged decorative cases made the photos feel more precious and intimate. To further protect the photographs, both tintypes and ambrotypes were encased in a brass mat cover, typically featuring an intricate embossed pattern. The interior of a case was lined with patterned velvet and padded to protect the image.

Collecting Civil War Portraits

Although attitudes towards the Civil War and its memory have changed in recent decades, a very active group of collectors have remained for Civil War images and portraits. If you want to start a collection or resell these images, there are a few things worth keeping in mind.

When looking at photos to purchase, pay attention to the quality of the image. Many ambrotypes and tintypes from this era have surprisingly crisp, detailed images. Some attribute this contrast and sharpness to a higher level of silver in the emulsion. Sharp, clear images command higher prices than those that are blurry. Collectors also prize portraits that depict soldiers holding items of the time, particularly those related to War, like canteens, weapons, hats, and musical instruments.

Keep an eye out for hand-painted images, as some will have added rosiness to cheeks or blue tint to a uniform. As color photographs were decades away from existing, hand-tinting was often done, at an added expense, to add interest and depth to some images of the time. Also, keep an eye out for portraits of those less commonly represented, like African, Black, and Native American soldiers, or those depicting family members alongside those in the war. Finally, carefully consider the case’s condition—ensure the glass is not broken, the mat is not too heavily tarnished, and the book is in decent shape. Portraits can be found for a few bucks to a few hundred dollars, depending on the knowledge level of the seller. If an image depicts something rare, it may be worth thousands of dollars.

While we may all have different relationships to this troubled time in America’s past, there is a powerful, quiet beauty to these portraits that anyone can appreciate. These images tell a story that monuments and books cannot speak and allow us to look directly at those involved and those affected. Despite the fact it has been over a hundred and fifty years since the Civil War, these images allow us to come face to face with the past.

Megan Shepherd is a curator, freelance writer, and artist. She has worked in fine art museums for a decade and holds two master’s degrees in the field. When she takes a break from art, she enjoys science-fiction books, antiquing, backpacking, and eating her weight in Dim Sum.

WorthPoint—Discover. Value. Preserve.

The post Face to Face with the Past: Collecting Civil War Portraits first appeared on WorthPoint.