Every Great Writer is a Great Deceiver: Vladimir Nabokov’s Best Writing Advice

Posted by admin on

Ten years ago, Geoff Dyer compiled a list of advice for aspiring writers. It contains mostly good advice, but I’m afraid I can’t quite get behind #3, despite its obvious utility: “Don’t be one of those writers who sentence themselves to a lifetime of sucking up to Nabokov,” Dyer says. Well, I get why you shouldn’t—but how could you not? Vladimir Nabokov is probably the best constructor of sentences I’ve ever read; our most word-drunk writer, our most deliriously beautiful snob. Personally, I’ve already sentenced myself to a lifetime of sucking up. If you have, too, here’s a collection of some of his best writing advice to help you get a little closer (though honestly, he would hate this), plucked from lectures and interviews.

Study other artists . . .

A creative writer must study carefully the works of his rivals, including the Almighty. He must possess the inborn capacity not only of recombining but of re-creating the given world. In order to do this adequately, avoiding duplication of labor, the artist should know the given world. Imagination without knowledge leads no farther than the back yard of primitive art, the child’s scrawl on the fence, and the crank’s message in the market place. Art is never simple.

–from an interview with Alvin Toffler, published in Playboy, January 1964

. . . But don’t waste time on imitation.

Derivative writers seem versatile because they imitate many others, past and present. Artistic originality has only its own self to copy.

–from Nabokov’s interview with Hebert Gold, published in the Summer/Fall 1967 issue of The Paris Review

Pluck fiction from the world around you.

The art of writing is a very futile business if it does not imply first of all the art of seeing the world as the potentiality of fiction. The material of this world may be real enough (as far as reality goes_ but does not exist at all as an accepted entirety: it is chaos, and to this chaos the author says “go!” allowing the world to flicker and fuse.

–from Nabokov’s 1948 lecture “Good Readers and Good Writers”

Embrace your role as deceiver.

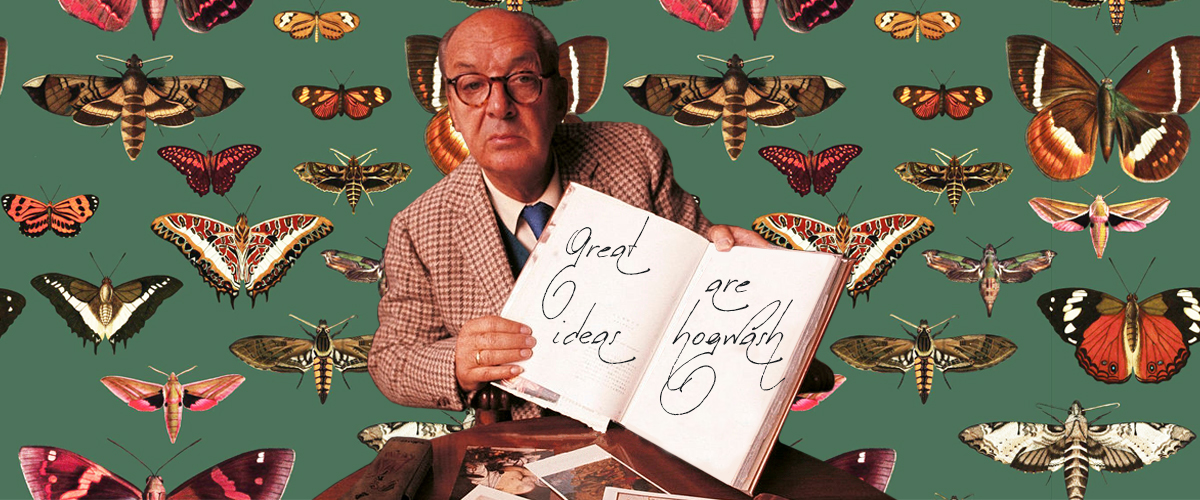

Literature is invention. Fiction is fiction. To call a story a true story is an insult to both art and truth. Every great writer is a great deceiver, but so is that arch-cheat Nature. Nature always deceives. From the simple deception of propagation to the prodigiously sophisticated illusion of protective colors in butterflies or birds, there is in Nature a marvelous system of spells and wiles. The writer of fiction only follows Nature’s lead.

–from Nabokov’s 1948 lecture “Good Readers and Good Writers”

Originality is everything.

The force and originality involved in the primary spasm of inspiration is directly proportional to the worth of the book the author will write. At the bottom of the scale a very mild kind of thrill can be experienced by a minor writer, noticing, say, the inner connection between a smoking factory chimney, a stunted lilac bush in the yard, and a pale-faced child; but the combination is so simple, the threefold symbol so obvious, the bridge between the images so well-worn by the feet of literary pilgrims and by cartloads of standard ideas, and the world deduced so very like the average one, that the work of fiction set into motion will be necessarily of modest worth. On the other hand, I would not like to suggest that the initial urge with great writing is always the product of something seen or heard or smelt or tasted or touched during a long-haired art-for-artist’s aimless rambles.

Although to develop in one’s self the art of forming sudden harmonious patterns out of widely separate threads is never to be despised, and although, as in Marcel Proust’s case, the actual idea of a novel may spring from such actual sensations as the melting of a biscuit on the tongue or the roughness of a pavement underfoot, it would be rash to conclude that the creation of all novels ought to be based on a kind of glorified physical experience. The initial urge may disclose as many aspects as there are temperaments and talents; it may be the accumulated series of several practically unconscious shocks or it may be an inspired combination of several abstract ideas without a definite physical background. But in one way or another the process may still be reduced to the most natural form of creative thrill—a sudden, live image constructed in a flash out of dissimilar units which are apprehended all at once in a stellar explosion of the mind.

–from Nabokov’s lecture “The Art of Literature and Common Sense”

Be storyteller, teacher, and (most importantly) enchanter.

There are three points of view from which a writer can be considered: he may be considered as a storyteller, as a teacher, and as an enchanter. A major writer combines these three—storyteller, teacher, enchanter—but it is the enchanter in him that predominates and makes him a major writer.

To the storyteller we turn for entertainment, for mental excitement of the simplest kind, for emotional participation, for the pleasure of traveling in some remote region in space or time. A slightly different though not necessarily higher mind looks for the teacher in the writer. Propagandist, moralist, prophet—this is the rising sequence. We may go to the teacher not only for moral education but also for direct knowledge, for simple fact . . . Finally, and above all, a great writer is always a great enchanter, and it is here that we come to the really exciting part when we try to grasp the individual magic of his genius and to study the style, the imagery, the pattern of his novels or poems.

–from Nabokov’s 1948 lecture “Good Readers and Good Writers”

You must have some talent to start with—and then you need to develop your style.

Style is not a tool, it is not a method, it is not a choice of words alone. Being much more than all this, style constitutes an intrinsic component or characteristic of the author’s personality. Thus when we speak of style we mean an individual artist’s peculiar nature, and the way it expresses itself in his artistic output. . . A mode of expression can be perfected by an author. It is not unusual that in the course of his literary career a writer’s style becomes ever more precise and impressive, as indeed Jane Austen’s did. But a writer devoid of talent cannot develop a literary style of any worth; at best it will be an artificial mechanism deliberately set together and devoid of the divine spark.

This is why I do not believe that anybody can be taught to write fiction unless he already possesses literary talent. Only in the latter case can a young author be helped to find himself, to free his language from clichés, to eliminate clumsiness, to form a habit of searching with unflinching patience for the right word, the only right word which will convey with the utmost precision the exact shade of intensity of thought. In such matters there are worse teachers than Jane Austen.

–from Nabokov’s lecture on Jane Austen

After all . . .

Style and structure are the essence of a book; great ideas are hogwash.

–Nabokov to his students, as reported by John Updike in the introduction to Lectures on Literature

Don’t feel like you have to start at the beginning.

All I know is that at a very early stage of the novel’s development I get this urge to collect bits of straw and fluff, and to eat pebbles. Nobody will ever discover how clearly a bird visualizes, or if it visualizes at all, the future nest and the eggs in it. When I remember afterwards the force that made me jot down the correct names of things, or the inches and tints of things, even before I actually needed the information, I am inclined to assume that what I call, for want of a better term, inspiration, had been already at work, mutely pointing at this or that, having me accumulate the known materials for an unknown structure. After the first shock of recognition—a sudden sense of “this is what I’m going to write”—the novel starts to breed by itself; the process goes on solely in the mind, not on paper; and to be aware of the stage it has reached at any given moment, I do not have to be conscious of every exact phrase. I feel a kind of gentle development, an uncurling inside, and I know that the details are there already, that in fact I would see them plainly if I looked closer, if I stopped the machine and opened its inner compartment; but I prefer to wait until what is loosely called inspiration has completed the task for me. There comes a moment when I am informed from within that the entire structure is finished. All I have to do now is take it down in pencil or pen. Since this entire structure, dimly illumined in one’s mind, can be compared to a painting, and since you do not have to work gradually from left to right for its proper perception, I may direct my flashlight at any part or particle of the picture when setting it down in writing. I do not begin my novel at the beginning, I do not reach chapter three before I reach chapter four, I do not go dutifully from one page to the next, in consecutive order; no, I pick out a bit here and a bit there, till I have filled all the gaps on paper. This is why I like writing my stories and novels on index cards, numbering them later when the whole set is complete. Every card is rewritten many times. About three cards make one typewritten page, and when finally I feel that the conceived picture has been copied by me as faithfully as physically possible—a few vacant lots always remain, alas—then I dictate the novel to my wife who types it out in triplicate.

–from an interview with Alvin Toffler, published in Playboy, January 1964

In the end, it’s the little things.

Caress the details, the divine details!

–Nabokov to his students, as reported by John Updike in the introduction to Lectures on Literature